In the summer of ‘61, an enterprising young local booked the great Satchmo to play a show Collingwood. Then the band’s bus broke down, and things got interesting.

by Geoff Taylor

On July 21, 1961, a humid Friday evening, Louis Armstrong and His All Stars performed at the Collingwood Community Arena and then promptly got stranded in town for the night, showing up at a late-night house party packed with townsfolk, including my parents. This is the story of that evening which became legend, the night Collingwood partied with Satchmo.

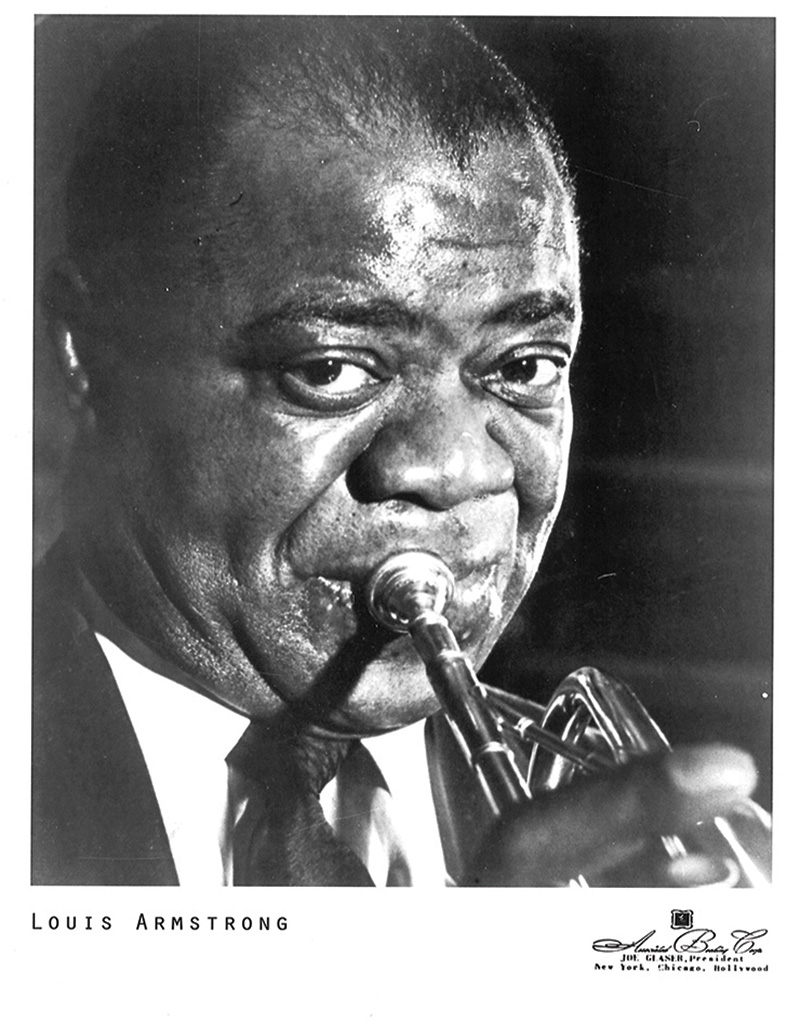

Louis Armstrong was the first truly global superstar with hit records, major movies and sold out tours on every continent. His was the face of jazz music. His impossibly wide smile and trademark white handkerchief were as recognizable as his gravelly vocals and epic trumpet playing.

By 1961, Louis Armstrong had been a musical force in five decades. The dangerous fad of rock ‘n’ roll had come and gone. Elvis was in the army. Costs had rendered the travelling big band era a memory, forcing Armstrong to reduce his touring act to a seven-piece band. Armstrong’s schedule was gruelling, with over 300 shows a year.

Even his first heart attack in 1959 barely slowed him down. Younger players left because they couldn’t maintain Armstrong’s pace. When the superstar’s bus rolled into Collingwood a week before his 60th birthday, he was already an old man.

Louis Armstrong in Collingwood. Left to right: Dee Dee Bryan, T.J. Brown, unknown, Wayne Hartle, Buddy Brown, Trummy Young, Louis Armstrong, unknown, John Sheffer, Frank Bryan, Roger Lockhart, David Christie.

In the summer, the typical draws at the Collingwood Community Arena were Wednesday night wrestling and Monday night bingo. The anticipation for the great Satchmo was incredible. Fans had seen him in movies such as Pennies from Heaven and High Society. TV appearances on the Ed Sullivan Show brought him into living rooms. Local dance bands like Wint Sparling and the Melody Men were revered but Louis Armstrong was the real thing. This was a first chance to see genuine New Orleans jazz performed in person. Fifteen hundred fans packed the arena paying two dollars a ticket.

The concert was organized by the Junior Chamber of Commerce (the Jaycees). Frank Bryan, an entrepreneurial fundraiser for the Jaycees, was 24 that summer. He reached out to Armstrong’s management about a Collingwood show. Bryan knew Louis Armstrong was performing a four-concert tour of Ontario with the closest booking at Dunn’s Pavilion (now The Key to Bala). A Friday night was blank on their itinerary.

“I reached out to the tour manager. We agreed to the booking over the phone,” recalls Bryan, who now lives in Markham. Bryan also arranged for a small reception at his family’s gracious Minnesota Street home for Jaycee members and the band.

Honoured that Satchmo was playing in Collingwood, the crowd dressed for the occasion. The Enterprise-Bulletin reported “spontaneous applause greeted the first notes as each selection was immediately recognized.” The silent, seated audience was in “rapt attention and ready appreciative response” as Armstrong and his band performed from a makeshift stage of the wrestling ring. Armstrong made “trademark use of his brow-mopping handkerchief—defrosting, he called it.” Signature tunes such as “When the Saints Go Marching In”, “Mack the Knife” and “La Vie En Rose” kept the audience mesmerized.

“Jaycee president Buddy Brown tried to convince people to dance but we just wanted to sit, afraid to miss a note,” recalls my mother, Helen Taylor, who was 24 at the time and attended the concert, and the party afterwards, with my father.

The Collingwood firehall was on Ste. Marie Street behind the arena. Louis Armstrong’s tour bus had limped into town and parked beside the firehall. The vehicle was making “god awful noises and burning blue smoke,” recalled my uncle, Ron “King” Taylor, who was a new firefighter at the time. Firefighters called the heavy equipment mechanic, Lyle Dickey, from Hanna Motors to repair the bus. Word got out about the small reception at Frank Bryan’s. Bryan called friends (including my parents) who lit up the town’s party lines and descended on the house. “My mother claimed half the town showed up,” Bryan recalls, “and wasn’t too happy the next morning with the number of empty bottles all over our lawn.”

Armstrong himself held court in the kitchen telling stories and trading jokes. “It was as if a movie star had stepped off the screen of the Gayety Theatre and come to life,” my mother recalls. Bryan remembers Armstrong as relaxed and convivial. “He told of making films with Frank Sinatra, Grace Kelly and Bing Crosby (his favourite singer).

About stopping a civil war on his tour of the Congo the previous year.” Armstrong started out playing in the New Orleans Colored Waif’s Home for Boys at 12 and had performed for royalty around the world. He was excited about the album he had just recorded with Duke Ellington.

Satchmo spoke of his lifelong manager Joe Glaser who started out as an enforcer for Al Capone in North Chicago during the prohibition era. “Joe Glaser is the finest man I ever met,” he once said. Armstrong sought Glaser out in 1935 to be his manager. Glaser protected Armstrong from physical harm and guaranteed him enough money to live on.

Glaser booked the gigs, signed the contracts, paid the band, expenses and taxes, and provided Armstrong a comfortable salary for the rest of his life. Glaser kept the rest. Joe Glaser was accused of working Armstrong relentlessly to keep the money rolling in, but he kept Louis and His All Stars out of trouble. “All I got to worry about is blowing my horn,” said Armstrong.

Louis Armstrong was a self-professed daily consumer of Swiss Kris laxatives and cannabis. “I do like to take a little drag or so. I can gladly vouch for a nice fat stick of gage, which relaxes my nerves if I have any,” he once said. Armstrong told how he and his wife Lucille were charged with smuggling narcotics from Japan into Hawaii, resulting in being banned from performing in that state. He had written an ultimatum to his manager: “Mr. Glaser you must see to it that I have special permission to smoke all the reefers I want to when I want to or I will just have to put my horn down.” Satchmo demanded Glaser use his connections to get a permit to smoke “all over the world.”

“I’m no criminal. I can’t afford to be dodging cops, dicks and stool pigeons fearing that any minute I’m going to be arrested,” Armstrong was quoted in his 2012 biography.

According to Frank Bryan, “No jazz cigarettes were smoked at the party.”

Armstrong and the All Stars were treated as honoured guests at the Bryan home.

Armstrong spoke of the racism and segregation they dealt with on tours. His mixed-race band often lived on the bus as there remained hotels and restaurants that refused to serve African Americans in the U.S. Some were the very venues the band played.

Armstrong told of the time, “I’ve got $2,000 in my back pocket and nowhere to eat.”

Despite breaking down many colour barriers, Armstrong had a complicated relationship with the African American community. During the 1950s, he was criticized for not doing enough for Civil Rights. His stage persona was considered by some to be an old fashioned buffoon, or worse, an “Uncle Tom.”

“I don’t get involved in politics, I just blow my horn,” Armstrong once said. The Little Rock, Arkansas, school integration crisis broke his public silence. Armstrong gave a fiery interview where he declared, “It’s getting almost so bad a coloured man hasn’t got any country.” A State Department tour of the Soviet Union had been negotiated but Armstrong responded, “The way they are treating my people in the South, the government can go to hell,” claiming President Eisenhower was “two faced” and “had no guts.” Armstrong’s statements reverberated around the world. He received hate mail and death threats; radio stations destroyed his records. TV appearances were cancelled by sponsors. His tour schedule became even more far flung. Collingwood became an unlikely destination, all the more unique for the after-party that brought Satchmo to Frank Bryan’s living room.

That steamy night in ‘61, the party showed no sign of slowing down until the recently repaired bus rolled up Minnesota Street around 2:30 in the morning. Louis Armstrong and His All Stars posed for photos, said their goodbyes, stepped on the bus and rolled out of town.