“Voluntourism” is one way that travellers can have a meaningful impact—if done right, such as this locally based project

for the Dominican Republic.

By Laurie Stephens // Photography by Bryan Davies

Sometimes, it’s small things that make a huge difference. To displaced Haitians in the impoverished villages of the Dominican Republic, a water filtration system. Or safe electrical power so that children can read at night. Or a doctor’s office with a refrigerator to store insulin.

It may also be something as simple as showing you care.

In the small village of Lomas Blancas, about 50 ancianos—the original sugarcane cutters who migrated from Haiti in the 1960s and then lost their livelihood when the sugarcane companies left the Dominican—didn’t know how to write their names.

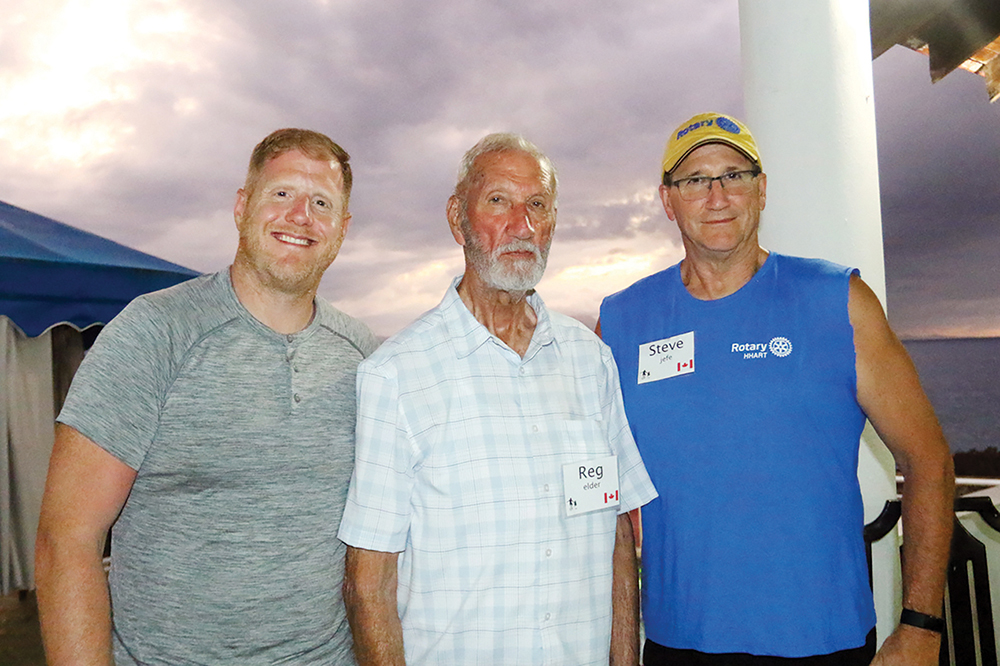

“So, the exercise when we went there was, ‘What is your name, we’ll show you how to write your name’,” says Steve Wallace, a member and past president of the Wasaga Beach Rotary Club. “I couldn’t believe the smiles and the squeals of excitement and joy.”

Wallace, 66, is the founder of the Rotary-sponsored Hispaniola Humanitarian and Relief Team (HHART). Over the past 12 years, he has recruited dozens of South Georgian Bay volunteers to spend one to three weeks of their vacation time in Dominican villages—called bateyes—that lack even the most basic services we take for granted.

Villagers live in cramped, barrack-like shacks made of wood, concrete and tin. Roads are typically dirt paths, and electricity and clean water are in short supply.

Wallace, a former Canadian Air Force and Air Canada pilot, led the first HHART service trip in 2010 to bring medical and dental services to the vulnerable population.

“We brought a little bit of medical expertise, a little bit of dental expertise, and we actually did surgeries,” he said. “I had bought a mobile dental kit, so it had a drill, a light, and it had suction, and we were off and running.”

Since then, HHART has made lasting improvements to the region’s healthcare. The best example is the Amigitos Community Centre that is run by the Norwegian charity Amigitos in Batey Pancho Mateo. The Centre has become a community hub that includes medical and dental clinics, a children’s play area, and a large kitchen used for delivering food programs for seniors and kids.

Over the years, HHART has helped fund equipment for the clinics and promoted the training of locals to work in the Centre; it has completely outfitted the doctor’s office with an examination table and diagnostic equipment.

Basic medical and dental care is a critical need in bateyes like Pancho Mateo where most of the residents are of Haitian descent and their rights are not fully recognized by the Dominican Republic government.

“The mission is to bring relief to these people, to help make their lives a little bit better, and to make their communities a little bit stronger. Capacity-building is what we’re really trying to do and let them sort the rest of it out.”

On Wallace’s first visit in 2010, the villagers were frantic to get an audience with a healthcare practitioner, says Wallace. Now a doctor and a nurse staff the medical clinic three afternoons a week.

“Now, people are casually walking in to see the doctor,” Wallace says. “They understand they have access to effective primary medical attention and treatment.”

Projects vary every trip. Last March, the focus was bringing safe electrical power to 45 homes. The project constructed basic electrical panels to save villagers from “hotwiring” their power source and risking a fire, and gave children light to read at night.

Other projects have repaired pumps for school bathrooms, and funded the building of cement roads over dirt paths, or the purchase of sports equipment for kids and supplies for Montessori schools.

“The mission is to bring relief to these people, to help make their lives a little bit better, and to make their communities a little bit stronger,” says Wallace. “Capacity-building is what we’re really trying to do and let them sort the rest of it out.”

For project participants from Canada, HHART is an opportunity to travel with a purpose, a particularly effective example of “voluntourism” in action.

Dr. Jennifer Simpson, 47, of Huntsville, has participated in HHART every year since 2012. She applies her skills as a naturopathic doctor in mobile clinics and performs other tasks as well. HHART has become a family affair. Her husband, both of her boys and her parents have all taken part in at least one trip. Most interesting to her boys—then aged 10 and 12—were the similarities they shared with the children in the villages, even amongst the poverty.

“They still like the same sports, they still like the same clothing,” she says. “If you give them a phone, they want to play the same games and they get addicted the same way our kids do if you hand them a device.”

What appeals to her about HHART is its commitment to community sustainability. She says a lot of organizations simply fly in to drop off used clothing and shoes, then quickly leave. These donations disrupt village entrepreneurs who are already trying to make a living selling used clothing.

Kyla Meadley, 31, discovered HHART through her father, Steve Meadley, who has been a member of the Rotary Club of Bracebridge for over 20 years. The chiropractic student from Thornhill took part in six missions and the experience has had a profound impact on her life.

She helped coordinate the medical teams—a role that motivated her to complete a master of science in global health in 2019, studying the barriers to healthcare for Haitian refugees in the Dominican Republic.

“Now that I’m in chiropractic, I’m starting to look at HHART and think of how I can extend it to have a chiropractic focus.

“Everything that we do has to come from a sustainable approach,” she adds. “We learned over the years that we need to have a focus that is going to make a long-lasting change.”

HHART’s most important legacy, says Dr. Simpson, is the villagers knowing that there are people who care about them and will continue to do so in the coming years.

“At the core of it, we must always remember that we’re here to build relationships with the local people,” she says. “And if at the end of the day, you haven’t connected with somebody on some level, whether it’s a construction worker helping out with a project, whether it’s a patient, whether it’s a child that you just sit and play with for a few minutes, then you’ve missed the boat.”