Birds you might spot on your next hike

story & illustrations by Anthony Jenkins

The sun is out, the skies are clear, the Bay is smooth and the temperature balmy. The outdoors beckons!

The exercise, invigoration and inspiration of putting one foot in front of the other across an eye-pleasing swath of nature is irresistible. And the soundtrack to any local hike, if you leave ear buds and iTunes behind, will be birdsong.

We live in a birder’s paradise. Southern Georgian Bay may be our home, but it’s home to more than 100 species of birds as well, and a good half of those cohabit with us year-round. Some you’ll see and know, some you’ll spot and not have a clue, and some shy species remain seldom seen, inhabiting wet, out-of-the-way nooks and brambled crannies.

You might spot a house wren (a chatty and cheerful songbird), a brown thrasher (a gifted mimic with a thousand-song repertoire), a wood thrush (spotty-bellied and seldom spotted), red-capped chipper sparrows (inept but avid nest-builders), barn swallows (who could just as easily be called boathouse swallows), pine warblers (who like pines … and warbling), or others from among a local avian cavalcade of nuthatches, thrushes, owls, orioles, creepers, jays, juncos, robins, or even the odd misdirected emperor penguin (okay, we made that one up). Birds provide hours of fun, free entertainment, and they’re all around us.

So get out, look around and listen up. You may not be, or become, a birder, but enjoying a hike, spotting a pretty little magnolia warbler in its natural habitat, and hearing it serenading you from a beautiful bower, will be very much its own reward.

Even for a woodpecker, the northern flicker sports plumage that is complex and beautiful.

Northern Yellow-Shafted Flicker

The northern flicker is a woodpecker that didn’t get the memo.

It’s a medium-sized woodpecker that doesn’t peck wood. It’s more of a groundpecker, its preferred diet being ants – particularly succulent ant larvae, which it spears with the hardened tip of its two-inch-long tongue.

It will also eat butterflies, flies, and bugs it uncovers from prised-open cow patties. Look for flickers on the ground in open areas, fields, parks and yards. But not in winter. Unlike other woodpeckers, they head south.

Even for a woodpecker, the northern flicker (also known as a yellowhammer, yarrup or gawker bird) sports plumage that is complex and beautiful: brown face (males wear a black ‘moustache’), grey crown, red nape crescent, black ‘necklace’ at its breast, upper belly and wings barred and black-spotted.

The yellow-shafted flight feathers, just visible from the side, distinguish the yellow-shafted flicker from its red-shafted cousins who are not seen around Georgian Bay, or anywhere in eastern North America.

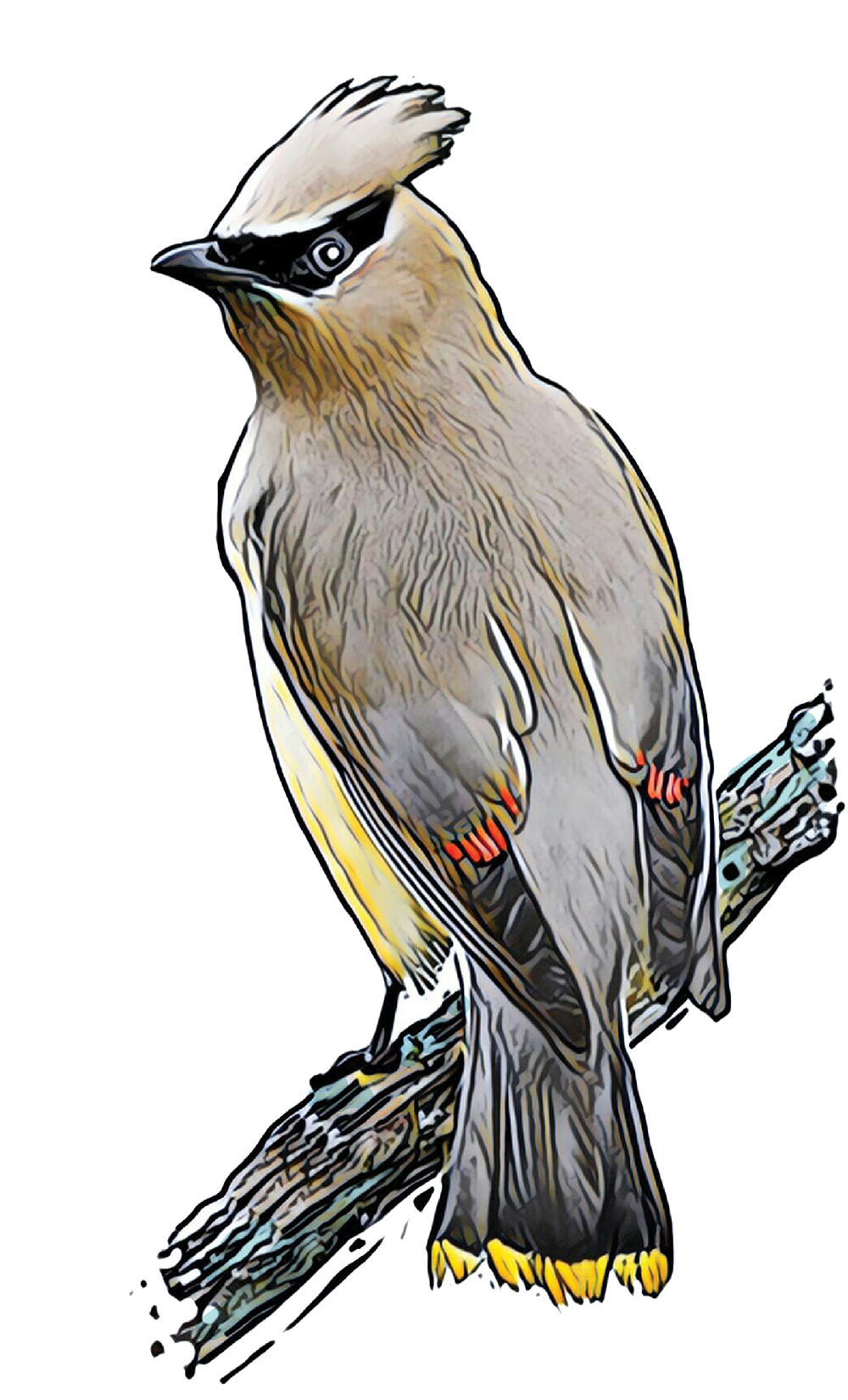

Cedar Waxwing

These plump, pretty birds are decorated in an eye-pleasing blend of cinnamon, grey and yellow, with a black bandit mask, slim yellow tail band and distinctive and telling (more and more prominent with age) red ‘fingertips’ to the wings. The ‘wax’ in the name is said to come from a long-ago fancy that those ‘fingers’ appear to be dipped in red sealing wax.

The ‘cedar’ comes, maybe, from a winter staple of their diet, cedar berries. For waxwings it is berries, more berries, and fruit year-round, with an occasional side of insects in summer.

Spotting a solo waxwing is rare. Social birds, they are happiest in flocks. You’d never call flocks of waxwings ‘choirs,’ however. Poor songbirds, they emit thin, tuneless whistles.

Waxwing flocks may be seen locally. Or not. They’re unpredictable nomads with no fixed address. Try looking in the margins of forests, along shrubby riverbanks or in especially berry-bearing suburban gardens. But if you spot a waxwing and his good-time buddies staggering around your yard, be kind and leave them be. Berries ferment; they’re drunk!

Red-winged Blackbird

The male red-winged blackbird is just that, when he chooses: a medium-sized glossy black bird with a sharp, pointy beak and vivid red shoulder flashes (called epaulettes) bordered in yellow.

In spring breeding season when claiming and defending a reedy wetland territory – from swanky swamp to low-rent drainage ditch – his red wing flashes are noisily displayed as both allure to mates and warning to rivals.

His females (Monogamy? No thanks!) sport the dull mottled browns of their nesting turf. Both sexes aggressively defend their territory, attacking much larger birds and harassing intruding humans. Bring binoculars – or a hardhat!

Outside breeding season, males mellow and appear to be mere blackbirds, coyly concealing those provocative red epaulettes. At those times, red-winged blackbirds can form in huge concentrations over croplands, meadows and open areas in woodlands, where they will ground forage on a smorgasbord of grains and seeds, often to the consternation of farmers.

His females (Monogamy? No thanks!) sport the dull mottled browns of their nesting turf. Both sexes aggressively defend their territory, attacking much larger birds and harassing intruding humans. Bring binoculars – or a hardhat!

Pileated Woodpecker

Much, much bigger than their petite cousins, downy or hairy woodpeckers, at up to 18 inches pileated woodpeckers are bigger than almost anything winged in local forests.

They are striking birds. Literally. They’re often heard rat-tat-tatting on dead or fallen trees before their big black body with jagged white neck stripe is spotted. Males add a red ‘moustache’ stripe.

With all that dedicated drilling, they’re seeking bugs – carpenter ants in particular – but will call anything creepy and crawly ‘lunch.’

Amid all the holes they leave seeking a meal, an oval hole betrays a one-season-only nest site. Abandoned pileated woodpecker cavities are favourites with other nesting birds, or even wildlife such as flying squirrels or martens.

Find, or hear, a pileated woodpecker hammering at your house and you don’t live in a hollow tree? Festoon the site with tin foil. They don’t like shiny. Want to attract them? Leave decaying trees standing and paint the bark about three metres up with a tasty home-made mix of lard, oatmeal, peanut butter and chopped dried fruit. No snacking!

Common Yellowthroat

Yes, this small, quick warbler does have an attractive yellow throat. It also has a plump, pale-yellow belly, long tail and short, rounded wings. Males wear a black mask bordered above with white.

Common and widespread, these pretty, furtive creatures are difficult to spot. They like a tangled, soggy habitat, prowling reed beds, the low dense vegetation around ponds and thickets, or the untidy tangles on the margins of marshes and streams where they seek out small insects and spiders.

In a switch, yellowthroat males are the monogamous ones. Females have a roving eye, a preference for bigger-masked males, and polyamorous intent. If, by the way, you spot a social grouping of warblers, you’re seeing a ‘bouquet’ of warblers, a ‘confusion’ or a ‘wrench.’

American Bittern

Think you’re going to spot an American bittern? Wanna bet?

The bittern is a common but rarely glimpsed heron, a stubby and solitary bird about half the size of a Great Blue Heron. It is the unlovely Where’s Waldo of wading birds, with mud-coloured plumage striped with white, and a devious disposition.

It can be found (good luck!) almost impossibly camouflaged against the shoreline reeds and rushes of large marshes and wetlands, which it slowly stalks preying on fish, frogs, crayfish and almost anything that swims, jumps or wriggles.

Making it even more challenging to spot, when startled, the bittern will extend its long, slim neck skyward and freeze, to better blend into its bullrush backdrop and virtually disappear. On a windy day, just for kicks, it may even sway with the grasses!

You are much more likely to hear an American bittern than see one. That odd, booming, pumping throb overheard at dusk? It’s the bittern you never saw. And from late September to early May, you won’t even hear one. When the wetlands begin to freeze, bitterns migrate south. Laughing.

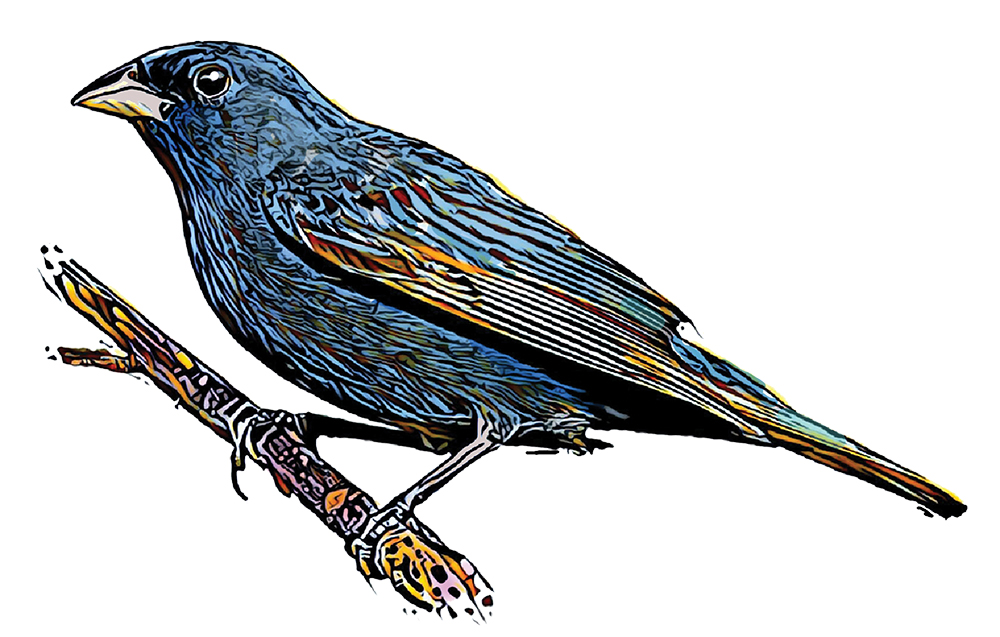

Indigo Bunting

Semantics and optics.

Like the sky or the sea, male indigo buntings – stocky, sparrow-sized birds – are not really blue, let alone indigo. They just look that way. Reflecting and refracting the blue light spectrum, they appear cerulean blue in the body, reaching indigo only about the head. The female’s plumage is a simple brown, with only hints of blue on the wings.

Those blue-looking males warble complex songs with gusto and perseverance all day long from high perches such as wires and poles. Their songs vary slightly by locale, much like regional accents, eh.

Farmers’ friends, indigo buntings’ summer diet consists largely of insects. In winter, they eat grains and seeds.

They can be spotted foraging in areas that haven’t been mowed, plowed, tended or groomed. Think untidy: scrubby roadside verges, overgrown fields bordering forests, thickets, ill-kept rail and hydro right-of-ways, the brush beside water courses. Don’t look on the fifteenth fairway.

And in winter, look south to Mexico, Costa Rica or the West Indies.

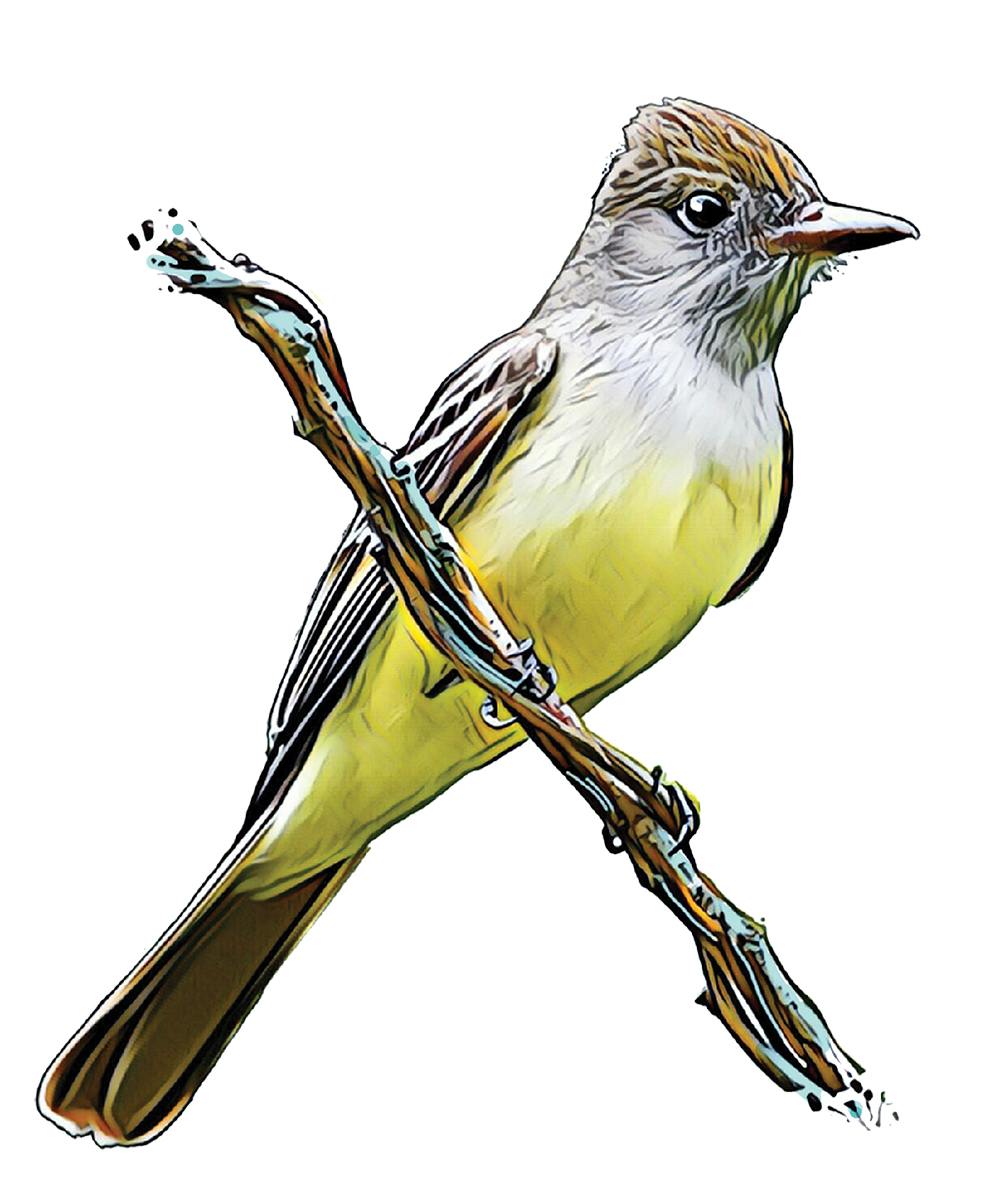

Great Crested Flycatcher

Look up. Way up. The great crested flycatcher lives and forages high up in the treetops. It is rarely, if ever, seen on the ground. These birds don’t walk. They don’t hop. They fly from place to place.

Observe them on high perches on the margins of deciduous forests, atop copses in parks, or on golf courses. They prefer unobstructed views over flatlands for seeking insect prey of leaf-crawling lunch taken on the wing in plunging attacks into the foliage. In less energetic moments, they will dine on fruits and berries.

These stout, largish (eight inches tall) birds have a thick black beak, dark grey plumage above and bright yellow below. However, you’ll need a ‘cherry-picker’ style hydraulic hoist – or binoculars – to get a really good look.

Downy Woodpecker

If you’ve seen a woodpecker in your back yard or at your feeder, it was probably a downy. If you didn’t fall in love with the sight of these pretty, amiable little acrobats in spotted pyjama plumage, you’re probably dead.

The smallest of the woodpeckers, downies seem comfortable at any angle on a tree trunk, balancing back against their stiffened tail. They’re ubiquitous in any open woodland, park, orchard or garden. They do great environmental service devouring destructive bug infestations, and mix cordially with other small birds and each other. What’s not to like?

The frequently heard rapid rat-a-tat-tat a woodpecker makes pecking at a tree is called ‘drumming.’ It’s a territorial claim and mating signal sent by either sex. When they’re drilling for a meal, they do so more slowly and quietly.

Downies are easily mistaken for their much larger cousin, the hairy woodpecker. Apart from size, they are almost identical. Look to the beak. The downy’s is relatively short; the hairy’s beak is as long again as its head. ❧