The inspiring story of Owen Sound’s Beth Ezekiel, the last remaining small-town synagogue in Canada.

by Laurie Stephens // photography by Jessica Crandlemire

If there is a defining characteristic of Beth Ezekiel synagogue, it would be perseverance.

The tenacious little shul (Yiddish for “school”) has served the Owen Sound Jewish community since 1947, when the existing congregation, led by Isaac Ezekiel Cadesky, purchased a church building and began to hold services.

Since then, Beth Ezekiel has seen its share of ups and downs, in both “normal” and pandemic times. Membership over the years has peaked at 50 to 60 families; now, it numbers below 30. Still, the synagogue possesses a stubborn desire to be a positive presence for the Jewish community and the town.

“Our synagogue is a place to meet and a place to learn and a place to study,” says Jeff Elie, president of the congregation and a member for 27 years. “This is how it’s functioned since it was established, and that’s how we want it to continue.”

Despite its size, Beth Ezekiel has an active and dedicated congregation. Services are held once a month and are usually led by Rabbi Steven Schonblum, who retired and moved from Toronto six years ago. He conducts services pro bono—a godsend to the struggling congregation. Outside of religious activities, members frequently get together for such activities as movie nights, sleigh rides or holiday celebrations at a waterfront home.

An important feature of the shul is the fact that it is liberal and egalitarian, meaning that men and women participate equally in all activities.

“We’re very diverse in our beliefs, to be honest,” says Ilene Charland, past president and 20-year member of the congregation. “We don’t necessarily have to be good friends, but we support each other.

“There’s a connection and I think that’s what keeps us together, that’s what keeps it special: the desire to keep things going in the face of challenges.”

Historically, Owen Sound has been home to Jews since the late 1800s, when merchants and tradespeople fled persecution in Russia and Eastern Europe and came to Canada to establish a new home. Cadesky himself was a refugee of the Russian pogroms, bringing his family to Owen Sound in 1906.

At first, regular services for this Jewish community were held in private homes and other local buildings. Then in 1947, the congregation purchased the Calvary Church, which has remained Beth Ezekiel’s home to this day.

There are assertions that Beth Ezekiel is the last remaining small-town synagogue in Canada. Indeed, the Grey Roots Museum and Archives conducted research in 2008 to document small-town synagogues in operation in Canada at that time. Owen Sound, with a population of just 21,000, was by far the smallest community to have an active synagogue, and since 2008, many of the others on the list have closed. Sault Ste. Marie, more than triple the size of Owen Sound, is the closest contender.

“When Canada was being settled, wherever there was a main street, there were Jews,” synagogue president Jeff Elie explains. “There were Jews selling clothes, Jewish tailors, Jewish shopkeepers, Jewish scrap rag-and-bone dealers—anything to eke out a living.

“They established synagogues, and communities, put down roots, and raised families. Now they’re gone—except for Owen Sound.”

From the outside, Beth Ezekiel is a modest, brown brick building located in a part of the town that has seen better days. But step inside the shul and you are immediately enveloped by a sense of peace. It is warm and inviting, the walls rimmed by stunning, colourful stained glass windows that tell stories of the member families.

“There’s a connection and I think that’s what keeps us together, that’s what keeps it special: the desire to keep things going in the face of challenges.”

Two sets of wooden pews face the aron hakodesh, or “holy ark,” an elaborate wooden cabinet that is located on the eastern wall of the synagogue, in keeping with tradition. The ark holds three hand-inscribed parchment Torah scrolls that are concealed from view by a burgundy-coloured, embroidered curtain. At times during a service, a Torah scroll is brought out and unrolled on the bimah—a raised platform in front of the ark—for the reading, in Hebrew and Aramaic, of the Five Books of Moses, known by non-Jews as the Old Testament.

The pews seat about 70 to 80 people, and they sit atop a wooden floor that has a story to tell as a catalyst for a resurgence of the synagogue.

In 2002, the floor began to sag in the middle because the main beam holding up the sanctuary had rotted. The entire floor was sitting on basement water pipes and the building was in danger of collapsing.

The synagogue didn’t have the $30,000 to fix the structure, so Beth Ezekiel held a fundraiser called “Rhythm and Jews.” The event was a phenomenal success and a critical turning point for a congregation that had been considering closing the shul because it couldn’t afford the repairs.

“It was such a thing—Jewish cooking, Jewish music, displays, dancing,” says Elie, the driving force behind the fundraiser. “We just threw open the doors and said, ‘Give us a hand, we need help, come in and contribute what you can to save the synagogue’.

“We’d never been open to the public before, and people came in droves. We not only met our financial objective, but our membership grew, and we gained this whole renewed sense of who we were and how we fit into the local Owen Sound community. And that was huge.”

The event even made The Canadian Jewish News, prompting interest from others in Ontario’s Jewish diaspora, including now-member and synagogue treasurer Eric Zweig, who, like Elie, is a Toronto transplant.

“The article was a catalyst for me to visit the synagogue—and then I joined,” says Zweig. “A lot of people who move away from Toronto aren’t super religious and really don’t care that they don’t have a place to pray. But if they know there’s an actual active Jewish community centre, some do get involved.”

Around the same time as “Rhythm and Jews,” one of Beth Ezekiel’s most distinctive features was born: the 15 stained glass windows that honour the congregation’s families.

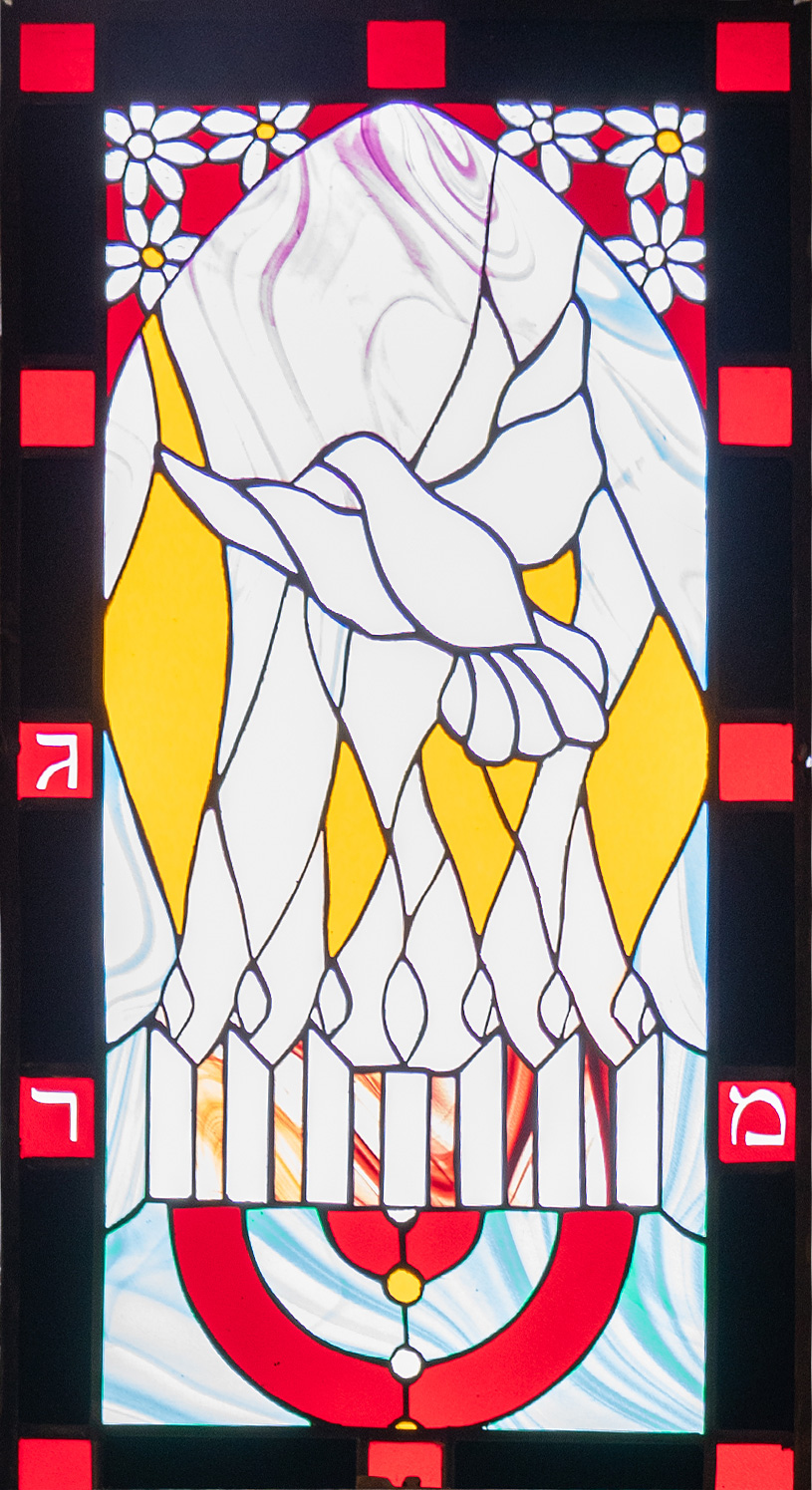

The first two were installed by Alisa Van Wyck in memory of her mother, Margalit Hoexter, who died in 1999. Alisa asked local artist Leigh Greaves to design the windows to symbolize her mother’s life and faith. They feature daisies—Margalit means Daisy in Hebrew—white calla lilies, a dove, the Star of David and the menorah.

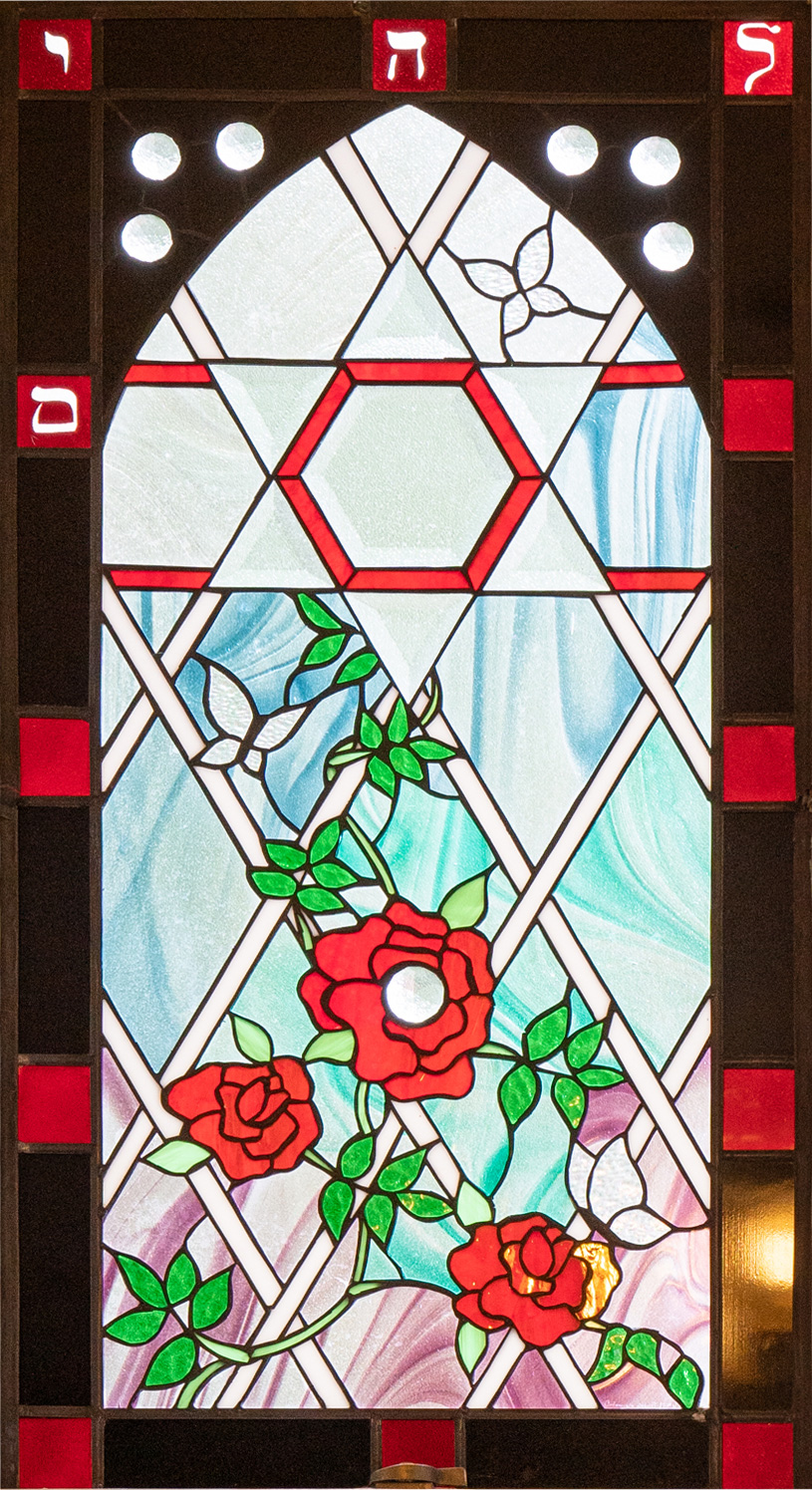

Elie’s family commissioned a window titled L’Chaim: To Life in celebration of the family. Images include a Star of David representing the family’s patriarch, David, and a large red rose in honour of Elie’s mother, Rose.

Another window, called The Journey, tells the story of the Levison and Rabovsky families.

The Levisons fled Germany after the infamous Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass), and travelled to China to escape the Holocaust and wait out the Second World War. Following the war, they settled in Owen Sound and Manfred Levison was hired by Cadesky to be a rabbi for the town’s growing Jewish population. Images in the window include air force wings in memory of Moses Rabovsky, who was killed in the war, as well as train tickets, railway tracks and a boat that symbolize parts of the two families’ journeys.

Beyond the walls of the synagogue, the congregation’s ties to the community run deep.

Beth Ezekiel supported the local mosque when it was vandalized, and in turn, the imam spoke of tolerance from the synagogue’s lectern during an event to express solidarity with Jews worldwide in the wake of the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting in 2018.

Around the same time as “Rhythm and Jews,” one of Beth Ezekiel’s most distinctive features was born: the 15 stained glass windows that honour the congregation’s families.

Around the same time as “Rhythm and Jews,” one of Beth Ezekiel’s most distinctive features was born: the 15 stained glass windows that honour the congregation’s families.

The first two were installed by Alisa Van Wyck in memory of her mother, Margalit Hoexter, who died in 1999. Alisa asked local artist Leigh Greaves to design the windows to symbolize her mother’s life and faith. They feature daisies—Margalit means Daisy in Hebrew—white calla lilies, a dove, the Star of David and the menorah.

Elie’s family commissioned a window titled L’Chaim: To Life in celebration of the family. Images include a Star of David representing the family’s patriarch, David, and a large red rose in honour of Elie’s mother, Rose.

Another window, called The Journey, tells the story of the Levison and Rabovsky families.

The Levisons fled Germany after the infamous Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass), and travelled to China to escape the Holocaust and wait out the Second World War. Following the war, they settled in Owen Sound and Manfred Levison was hired by Cadesky to be a rabbi for the town’s growing Jewish population. Images in the window include air force wings in memory of Moses Rabovsky, who was killed in the war, as well as train tickets, railway tracks and a boat that symbolize parts of the two families’ journeys.

Beyond the walls of the synagogue, the congregation’s ties to the community run deep.

Beth Ezekiel supported the local mosque when it was vandalized, and in turn, the imam spoke of tolerance from the synagogue’s lectern during an event to express solidarity with Jews worldwide in the wake of the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting in 2018.

The synagogue donates regularly to local interfaith causes, such as the Salvation Army’s Christmas dinner program, and it even contributed to the Anglican church’s fund to replace its spire. It also participates in programs like Doors Open, and the city’s annual winter Festival of Northern Lights, where the Beth Ezekiel sponsors an illuminated Hanukkah menorah.

And, the synagogue’s leadership continues to find ways to serve the local Jewish community.

In 2006, Beth Ezekiel asked Owen Sound if some plots in Greenwood Cemetery could be set aside for Jewish graves, since there is no Jewish cemetery in the region.

“I always found it a little sad that Jews who were born in Owen Sound, grew up in Owen Sound and raised families in Owen Sound were always buried in Toronto,” says Elie. “And they were buried among strangers.”

Now, a corner of the cemetery, bordered by a hedge and marked by a communal monument with Hebrew inscriptions, contains space for more than 100 plots that face east.

Elie said the cemetery helps local Jews connect with their ancestors. A Jewish tradition during the High Holidays is to visit the gravesites of loved ones and leave a little stone on the headstone. Local Jews can now go to the cemetery, pick up a stone, say a prayer, and put the stone on the communal monument, as if putting it on a headstone of their loved one who is buried elsewhere.

Since the Jewish section opened, synagogue members have noticed that other people have started putting stones on monuments in other parts of the cemetery—another sign of Beth Ezekiel’s impact on the broader Owen Sound community.

The synagogue’s presence is certainly worth preserving, says Elie. Declining attendance is a worry, members are aging, and attracting younger families has been difficult. But the idea of Beth Ezekiel closing its doors after 76 years of serving the Jewish community seems inconceivable.

“Beth Ezekiel is a story of struggle, it’s a story of perseverance, it’s a story of overcoming challenges,” says Elie. “We’ll get through it because we are very aware of what would happen if we close.

“There would be no organized Jewish life and certainly less diversity in the larger community. We would leave behind a huge hole, so that’s what keeps us going.”