With the demise of newspapers, how do we find the local knowledge that social media doesn’t deliver?

by Dan Needles // Illustration by Shelagh Armstrong-Hodgson

It’s getting harder than ever to know what’s happening around here. A couple of months ago, Metroland announced that 70 of its community newspapers in Ontario would be shutting down their print editions and moving to online only. In the same week, the province’s oldest surviving weekly, The Glengarry News, printed its last issue and shut its doors after 131 years. These announcements probably came as a shock to many rural residents, but the newspaper industry greeted the news with a collective shrug.

“I don’t think that [any of them] were really substantial papers ever,” sniffed a Carleton University journalism professor. He suggested that whatever services those little papers had to offer could easily be covered by Facebook.

Except they can’t. Just as a civil society requires local, regional and federal government, it also requires multiple levels of conversation and information. It’s all part of the sifting and sorting that a person needs to go through during the horrendously difficult process of making up one’s mind. Our own local paper went out of production a long time ago and the office building has served as a theatre and dance studio for at least 10 years now. We couldn’t do much about it at the time, but something has gone missing in the process, like the sound of a refrigerator that isn’t running or frogs not singing in a swamp.

My first real job out of school was “editor” of a weekly newspaper in Shelburne, Ontario, in 1974. No one would have called the Free Press & Economist “substantial” in those days either. It had a subscription list of 1,200, seldom ran more than 16 pages and often featured headlines like: WARBLE FLIES ON THE RISE. (The final issue of The Glengarry News had a front-page headline on the problem of buckthorn.)

I had no credentials for the job. When I applied I told the publisher I had no journalism training and he replied, “Do you have any other strong points you want to make in your favour?”

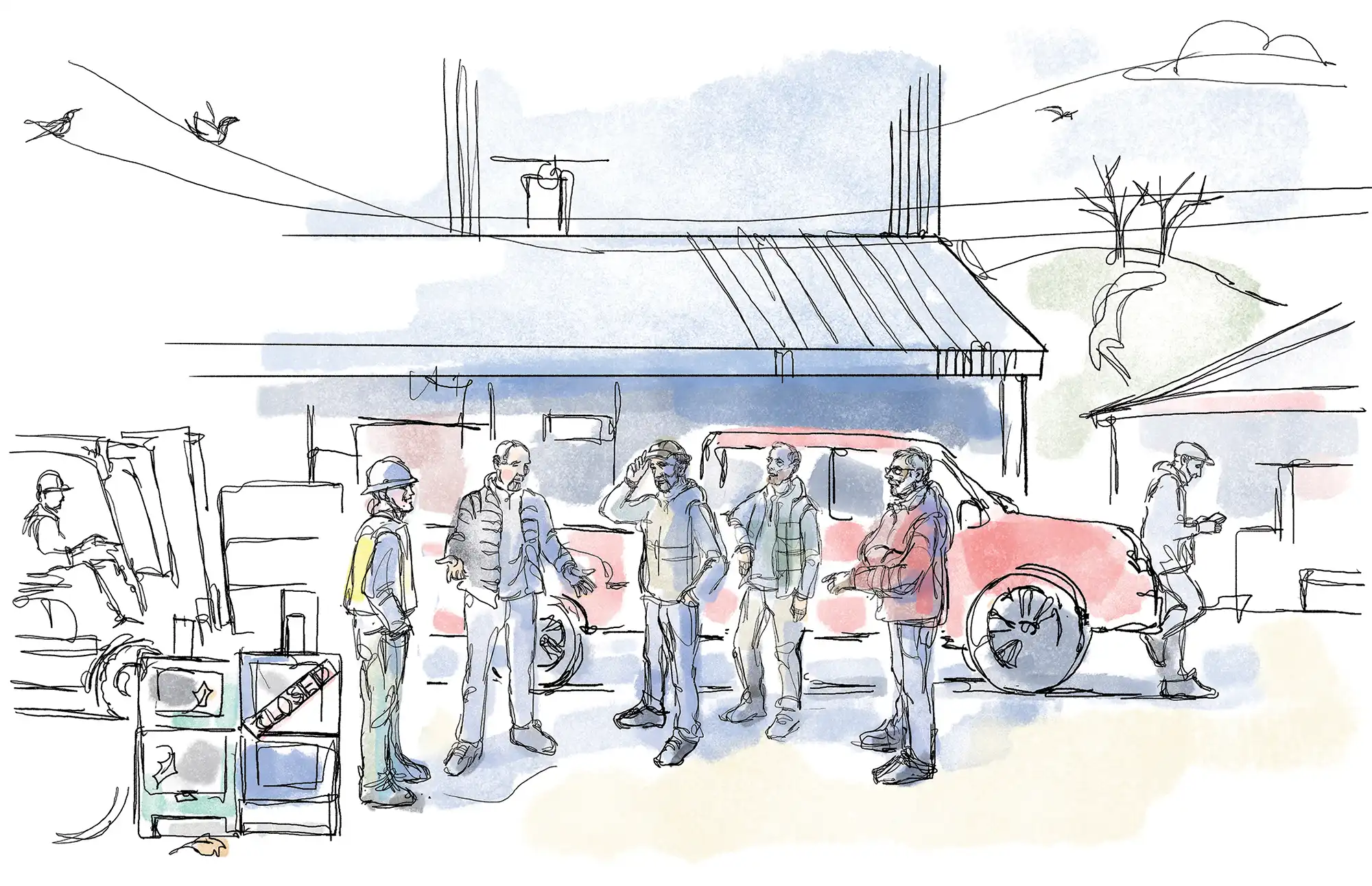

He wasn’t looking for a Carl Bernstein who would strip off the cozy illusions and comforting half-truths of Shelburne life. He wanted someone who understood that you had to stand in the same grocery line to buy bread with the people you were writing about. The sorting and sifting for this editor began while sitting on the Coke cooler in Bob Carruthers’ Gulf station across the street, where the guys would leaf through my paper in less than a minute and then tell me what really happened in town last week. The Gulf station coffee klatch became every bit as important to me as any town council or school board meeting.

Facebook is helpful for finding more detail about something you know has happened. But it is useless for staying up-to-date on the neighbourhood. You need a formal collection system for that kind of intelligence flow. And when the digital service has decided you don’t need to know about local births and deaths, lost dogs, hockey scores, euchre tournaments and auction sales, it can just as easily decide you don’t need to hear about the homeless camps on the edge of town or drugs and sexually transmitted diseases in the school either.

For the moment, there aren’t that many people interested in putting a dip net into the Mississippi of information flowing by us every day to tell us what is happening within walking distance. It’s hard to get paid a living wage for that kind of detail work. But the digital platforms for the old papers are still there, and whenever we decide that’s an important part of community life we can always pump oxygen back into them.

In the 1860s my hometown had no less than five weekly newspapers in its very first decade of life. Then it dwindled to one and back up to three, and now it’s back down to one that is only virtual. My feeling is that we are passing through one of those temporary lulls in the local news business and things will change before very long. In the meantime, the Driveshed Coffee Club remains my most reliable source of suspect information. That and the loading docks at Hamilton Bros. and B.J.S. Farm Supply. Oh, and don’t forget the family diner and D&L’s Variety on the highway.

Did you hear they saw a moose on the Min Baker Sideroad?

Playwright and humorist Dan Needles lives on a small farm in Nottawa. His latest book, Finding Larkspur: A Return to Village Life, was published by Douglas & McIntyre.