story by Dan Needles ❧ illustration by Bill Slavin

Not once in eighty-two years had Lorne Kennedy ever been lost on his own farm. But he was good and lost tonight, in driving snow not more than a hundred and fifty yards from the milk house door.

Not once in eighty-two years had Lorne Kennedy ever been lost on his own farm. But he was good and lost tonight, in driving snow not more than a hundred and fifty yards from the milk house door.

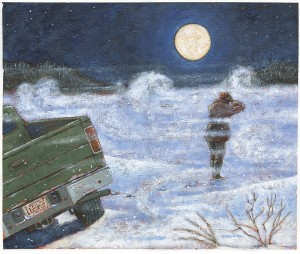

The odd thing was he could see the moon, right above his head. The snow was going by on both sides of him like a fast white river, but if he looked straight up, the sky was clear. A moon is no help above your head. It should be sitting away off on one horizon or the other and then you’d be sure which way was north. This one was round and full and grinning down at him and his foolishness.

It was all foolishness. One silly thing after another. People trying to jump-start him back into the business of living, when it was pretty clear he was done. And there were a couple of things he’d accomplished without any help from anyone else, like putting the truck in the ditch and trying to walk across this soybean field to the barn in blowing snow …

It was Julie Harkness who talked him into taking a part in her amateur theatrics. He didn’t like to say no to Julie when she asked him to do something.

He wasn’t crazy about the notion of playing a character so close to himself on stage, but it was only a walk-on, a sit-on, really. Derek Raven, who taught English at DCI, had adapted The Memory of Old Jack, a novella by Wendell Berry that follows an old Kentucky tobacco farmer around on the last day of his life.

All Lorne had to do was sit in a rocking chair with a Bible on his lap as scenes from his life unfolded around him. He only had a few lines, mostly things like, “Thank you, good woman,” and “There will be rain afore mornin’,” as if anybody talked that way anymore. The rest of the time he was supposed to doze and look old, which he was pretty good at. At the very end of the play, he was supposed to stop rocking and die. He was pretty well rehearsed for that, too.

He figured if he did this thing for Julie it might help get his daughter Connie off his case. Connie worked in a tower in the city doing human resources. Her kids were gone and she had all the time in the world to call him up and take his temperature and fret.

“We’re worried about you, Dad,” she said, sitting on the couch beside him one day between Christmas and New Year’s. “You have to get some of these feelings out in the open. It’s a journey you need to walk.”

He had no idea where she learned to talk like that. She grew up on a farm, for Pete’s sake. Stuff dies. You don’t breed, calve and milk sixty-five cows without a few visits from the grim reaper. If you have livestock, you’ll have dead stock.

“Mum was not a cow, Dad. You were a couple for most of your life. You’re not used to being alone like this. You should be in town, around other people.”

“I’ve got the dog. We get on pretty good.”

The dog was another touchy subject. Norma had never cared for dogs much. The week after she died, he drove over to a rough outfit in Proton Township where they had a big cream-coloured dog with sad brown eyes. The dog looked at him and they both knew right away they had nothing to fear from each other. The owners spoke no English, but it was clear they wanted rid of Bingo because he wasn’t mean enough to be a guard dog. Lorne gave them a hundred dollar bill, unsnapped the chain and Bingo jumped into the cab of the half-ton. He didn’t look back once as they drove away.

Bingo’s muzzle was dinner-table height, just right for carving little hunks of salami into it. Connie said he spoiled the dog, which was correct. The day Connie left, Bingo fired out the front door like a cannonball for his morning run and knocked Lorne off his feet. He hit his face on the arm of the porch swing. Connie saw the whole thing.

“That dog will be the death of you,” she said, holding a dishcloth full of ice against his eye.

“He’s just a pup,” said Lorne. “If you want to kill a farmer, just move him into town.” That afternoon he knocked a panel out of the veranda door and nailed an old floor mat over it so Bingo could come and go as he pleased.

At the play rehearsals, the others spent more time talking about what they should do instead of doing it. Derek decided tobacco was not a proper crop for a farmer and rewrote Old Jack to make him a dairy farmer, like Lorne had been.

“Then I should be in rubber boots,” said Lorne. He said it enough times that Derek let him wear the boots, probably just to shut him up.

The day of the dress rehearsal the mercury shrivelled to a dot and Lorne’s boots squeaked on the snow on the way to the barn. High cloud was blowing in from the northwest and there were rings around the sun.

“Snow afore morning,” he said aloud, trying to sound like he was from Kentucky. He forked steaming corn silage into the concrete manger and watched as the six Holstein heifers gathered it into their mouths with long grey-pink tongues. After Lancy Kendall bought the dairy herd from him, Lorne offered to feed a few heifers for the winter, partly to keep the frost out of the foundation around the milk house and mostly because he liked the smell of them. Norma always said that when she died she wanted to come back as one of her husband’s cows. He looked after them that well. He’d been watching these heifers for three months now, but had seen no sign of her.

Julie kept up the gentle deception that Lorne would be doing her a great favour if he gave her a lift into town for rehearsals in the half-ton, but he knew it was just her way of keeping an eye on him. She and Ollie lived across the road at the end of a long L-shaped lane that disappeared behind a slough filled with willows and emerged again at the top of the hill about half mile from Lorne’s house. Ollie cash cropped half the township with a fleet of tractors and combines, and had a row of storage sheds and grain towers on that hill that made the sun go down fifteen minutes earlier in Lorne’s kitchen at this time of the year. Ollie had rented Lorne’s fields ever since he sold the cows.

“You ready?” asked Julie, slipping into the truck that evening and bringing with her the smell of perfume and biscuits. She had brown eyes, like Bingo, and you could see the hurt in them, too. The laugh lines were still there, despite the loss of a son who slipped off the 4th Line and struck a tree on the night of February 23, eight years ago. She once told Lorne that people give you about six weeks to get over a thing like that. That seemed about the way it was. In the lineup at the funeral home for Norma’s visitation, men were already telling him it was time he sold the farm.

In the hall, Derek steered him into a dressing room where he was fussed over for an hour. They slathered Tan Peach Number Nine on his face, drew heavy lines on his forehead and neck, and sprinkled cornstarch in his hair. On stage, the lights were too hot and he instantly regretted the rubber boots. A small audience had turned up to watch the final rehearsal and Lorne suffered an attack of nerves. His lines were pasted into the Bible, but he couldn’t remember when to say them. At one point he said, “There will be snow afore mornin’,” and heard a sigh of exasperation from the back of the hall. The play was set in June.

Afterwards, he saw them huddled at the back, trying to decide what to do about him. He walked past, straight downstairs, still in his makeup and sat in the truck to wait for Julie. She joined him after a few minutes and patted his hand.

“In the theatre we say, ‘Don’t worry, it will be there on the night.’”

It was humiliating and he didn’t know why he had let himself be talked into it. Why didn’t they all just leave him alone? The wind was up on the sideroad. The snow blew across the ice-covered tarmac in hard little humps and the truck punched through them, tossing puffs up over the hood against the windshield.

“You call me the minute you get in your kitchen, Lorne Kennedy,” said Julie when he dropped her off. At the end of her lane by the sideroad, he accelerated through the last drift too hard and put the truck in the ditch.

Rubber boots without insoles are about the worst insulator there is. He could see his barn light across the road three hundred yards away. Those hard little drifts would have a crust on them, and with the wind northwest there would be three of them in his own lane. He figured the footing would be better through the soybean field where the wind would sweep everything clean. He started walking.

But there were drifts in the bean field, too. In the middle of the second drift the wind picked up the snow so it sliced into his face like a sword. It sucked the breath and the strength out of him in seconds. He staggered out the other side, walked another twenty paces with a mitt over his face, fighting for air, and then stumbled into a third drift. This time he knew he was in trouble. The wind was howling now and he couldn’t see the barn light. Couldn’t face into the wind and breathe and couldn’t walk backwards. Not good. Not good at all.

It was just so damn ridiculous. Lancy’s father had done something like this. He walked away from the nursing home twelve years ago and they found him next morning, hard as a concrete block. They put alarms on the doors after that and gave all the inmates electric bracelets. But Lancy’s father could be excused, not knowing anybody or anything at that point in his life. There was no excuse for this stupidity right here, steps away from his own barn. The ambulance people would find him lying in the snow with Tan Peach Number Nine on his face and cornstarch in his hair, and what would they make of that? What kind of fool do we have here?

The cold was moving dangerously up into his guts now and his feet were like clubs. He let out a wretched cry and stood with his eyes closed, trying to sob the air back in. He was startled by the fight in him, the suddenly fierce urge to live. And then he felt it. A muzzle under his hand. Bingo.

The dog bumped him gently and bounced away into the snow with a happy woof! crinkling his face into a grin and bowing his head in an invitation to play. When Lorne didn’t respond, the dog came back and bumped him again. This time he got his mitt under the dog’s collar and hung on. Bingo took his weight, held him and tugged him forward. His feet felt like they belonged to someone else. He stumped out of the drift and saw the field was clear now. He must be close to the barn. Then he saw the stone wall and pushed toward it, rounded the corner and the wind dropped.

He pounded the latch on the milk house door and fell into the silence of the milk room, gasping for air. It was still and moist from the warmth of the cows. He switched on the lights and collapsed on the show box that held his cow brushes and prize ribbons.

After a few minutes, he could breathe again. The dog watched him with his ears forward, brown eyes puzzled and gently mocking. “Who’s going to feed me my salami, if not you?”

Then the door burst open, and Julie and Ollie were with him, lifting him, speaking to him. Ollie carried him to the house as lightly as a child and laid him out on the couch by the pellet stove.

“You didn’t call me and we drove down and found your truck,” said Julie. “You could have died out there.”

He was shivering uncontrollably now, but the blood was moving again, bringing life back to his feet and the excruciating pain that comes with it.

He grinned, gripped her hand and said, “No siree. Can’t die now. Can’t die before I’m supposed to – up on stage in that rocking chair tomorrow night.” ❧