Whether in the wilds or in your back yard, our area is home to all manner of critters

story & illustrations by Anthony Jenkins

The ‘Great Outdoors’ it is called. Not The Okay Outdoors, not The Moderately Swell Outdoors, or The Passable-If-You’ve-Got-Nothing-Better-To-Do Outdoors. No, The Great Outdoors; verdant, natural, green and maybe garnished with a babbling brook or a secluded, skinny dip-able pond.

Out in The Great Outdoors, hikers, bikers, snowmobilers and just about any variety of ambulatory idler might find enjoyment, even come to feel at home. But the Great Outdoors is a home we share, or more correctly, a home they share with us. Critters. Animals. Wildlife.

Being outdoors, and being observant, you never know what you might see, or what might be seeing you, unseen, from the shadows or camouflaged, hiding motionless in plain sight.

You may not spy all God’s creatures, great and small, but herein, a small sampling of some possibilities if you are outside, on the lookout, or just plain lucky. In the case of a cougar or bear, very lucky (or very unlucky, depending on the outcome).

Some sightings will present a delightful encounter or leave you with a wildlife tale to tell. Other encounters, thankfully rarer, might become a no-sudden-moves, back-away-slowly brush with being something’s supper.

You never can tell. What is certain is, you’ll not encounter nature on the wing, hoof or paw while rooted to your sofa. So this fall, hit pause on the remote. Game of Thrones, season five, will still be there, bingeable, when you get back.

So get up, get out, and get looking.

But the Great Outdoors is a home we share, or more correctly, a home they share with us. Critters. Animals. Wildlife.

White-Tailed Deer

Fall is when local deer look their very best. They are healthily rounded with reserves of fat stored for the coming privations of winter. Their thicker, lusher and slightly greyer winter coat has appeared, and the antlers of males (known as stags or bucks) are at their largest and most characteristic.

Antlers are shed each January and re-grow bigger each year, depending on health, genetics and quality and quantity of food. Females, called does or hinds, rarely grow antlers.

One of the true wonders of the woods is encountering a deer, even at a distance, and exchanging a mutual, extended, deer-in-the-headlights stare.

The staring deer is on high alert, ears pricked up for any sound, immobile and intent, trying to make out what you are. Tawny, silent, slim and still, a deer will seem to merge into slanting shadows of the forest. He or she is waiting for you to make the first move.

This shared stare can last for 15 minutes or more. Then, if you have become familiar, the calmed and graceful creature may just resume eating. More likely, erring for caution, it will ‘flag’ (raise its characteristic tail displaying white underside and buttocks) as a warning to nearby deer, often fawns or members of a small family group.

Why do hunters wear bright orange? It’s not a fashion statement. Deer are bichromatic, meaning their vision is limited to the blue/yellow side of the spectrum. They can’t see reds and oranges.

And they can’t shoot back.

Eastern Cottentail

Cute. Pest. Lunch. Three descriptions of a fluffy little bunny depending on whether you’re a child, a farmer, or anything in the outdoors with fangs, claws and an appetite.

Cottontail rabbits – which differ from angular hares with larger ears, legs and solitary dispositions – are small, gregarious rodents that wear a grey-brown coat year-round, have ears that can swivel independently, and enjoy an active sex life.

Very active. Males (bucks) are sexually active at one month of age, females (does) at four months and are able to produce five litters of four to five babies (kits) a season. You do the math.

Well, you needn’t bother. Rabbit mortality is shocking. Despite being ever-alert and canny – escape routes in the open are pre-planned and multiple exits from burrows dug – cottontails are easy prey. Even with a superb sense of smell and hearing, great camouflage, and impressive zig-zagging getaway speed, only 15 per cent of cottontails will survive their first year, and two is ‘old’ for a rabbit (beyond captivity, where they might reach the age of 10).

Cottontails are a staple in the diet of almost every woodland carnivore you can think of – and some you might not, such as owls and raptors, who are in fact rabbits’ principal predators.

Rabbits are killed and consumed as a diet staple in the wild. But they can get their licks in. Their first defence is to freeze, their second to flee. Their final option is fight, and it is from that situation the term ‘rabbit punch’ (an illegal blow in prize fighting) comes. When cornered, a rabbit will leap high over a foe, delivering a swift long-legged kick to its neck or the back of its head in passing.

Fox

Half the size of a coyote and dwarfed by a wolf, sighting a dainty, three-foot-long, two-foot-tall, gorgeously coloured and bushy-tailed fox in the wild will bring a smile of aesthetic appreciation to the face of almost anything that isn’t a chicken.

Fox personalities and social life are delightful as well. Playful, mated for life, both sexes – males known as tods and females known as vixens – are attentive and loving parents. Foxes live in stable family groups in burrows dug into slopes, always marking their territory – which these highly adaptable creatures increasingly share with humans.

Sightings within towns and cities are becoming common. Foxes pose no threat to people and as the larger carnivores who prey on them are driven away by human development, foxes are moving in, adapting, co-existing, and doing great service in ridding human environments of rodent pests.

The biggest menace to foxes cohabiting with humans is domestic pets – cats and dogs – which prey on the young kits.

Foxes are shy, sly, fast and agile. They can hear the faintest mouse squeak at 100 metres. Hunting, they can leap two metres straight up, using their tail as a rudder to steer, mid-air, into a characteristic, graceful pounce.

Fox personalities and social life are delightful as well. Playful, mated for life, both sexes – males known as tods and females known as vixens – are attentive and loving parents.

Coyote

The coyote suffers in comparison to the cuter, prettier fox, but it is an equally adaptive omnivore increasingly prevalent in urban areas.

Because of its often lean, scruffy appearance, nondescript brindle coat, and size that enables it to prey on domestic sheep, goats and family pets, coyotes have a reputation as a dangerous scrounger.

Pronounced as a KYE-oat out west and kye-OH-tee hereabouts, this far-from-endangered 20- to 50-pound predator is the size of a medium dog. But it can be distinguished from a dog – even a wild one – by its habit of running with its tail down, by its sharply pointed ears that never droop, and by a much wider range of vocalizations (the widest in the canine family). A coyote will huff, growl, whine, yip, yelp, howl and sing.

These calls must be pretty persuasive, as coyotes can and do breed with both wolves and dogs, producing coywolf and coydog offspring.

Quirky aside: a real life Wile E. Coyote would catch the roadrunner every time. A coyote is twice as fast as any smart-Alec, long-legged ground bird.

Virginia Opossum

The possum and the opossum are the same thing, unless you live in Australia, where the possum is another thing altogether. The Aussie possum is tiny, cute, big-eyed and fuzzy. The North American possum is none of those things.

It is cat-sized, beady-eyed and pale, with a slim, snouty face only a mother could love. A near-sighted mother.

The possum is as odd as it is ugly. It is North America’s (excluding Mexico) only marsupial, carrying its young in a pouch, then on its back. The female has two vaginal tracts, the male a bifurcated (forked) penis, and both sexes have a prehensile tail used like a fifth limb in climbing. Possums love to eat carrion, eggs, frogs, seeds, grain and insects (they can consume up to 5,000 ticks a year).

Even more unusual is the possum’s defining defensive strategy. When faced with a predator, it plays possum; it acts dead. Very dead: falling over stiff, tongue protruding, frothing at the mouth with a glassy-eyed stare.

There’s more! It emits a powerful stench from its anus, mimicking the smell of rotting flesh. It is said to be smart (it tops domestic cats and dogs in animal intelligence tests) but its I’m-dead-and-rotting act is involuntary, triggered by stress in the face of imminent danger.

As its name implies, the Virginia Opossum was once a denizen of deep-south USA. Global warming has seen its range extend into Canada, to its evolutionary dismay; its hairless tail and ears are subject to frostbite over winters in The Great White North.

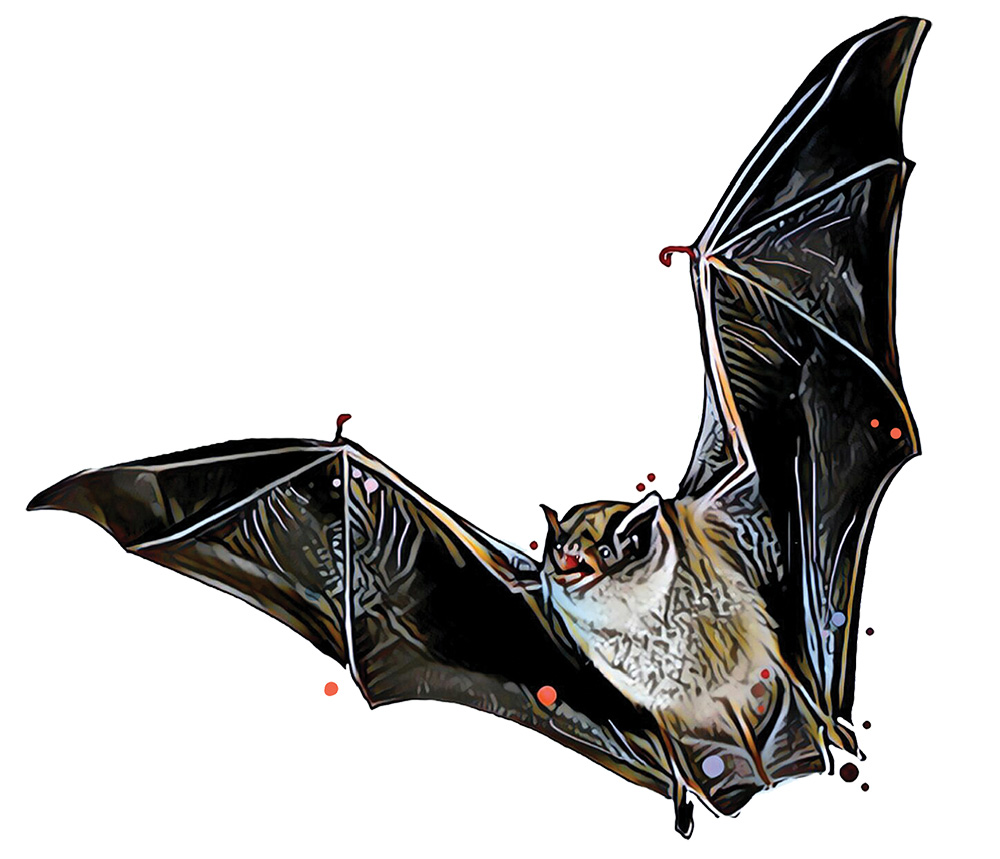

Little Brown Bat

Who doesn’t like bats? Well, almost everybody, it seems.

There are eight species of bats in Ontario and by far the most common is the thumb-sized Little Brown Myosis Bat.

Bats are the only flying mammal. Flying squirrels merely glide and lie about it. In the pantheon of The Ugly-But-Interesting, they rank right up there with Iggy Pop.

Bats are harmless nocturnal insectivores with an undeserved reputation. Only the South American vampire bat drinks blood, and then very little and from cattle. Myosis bats eat insects. Insects in great quantities. Bats come out at night, when insects do and predators don’t. They can eat 12,000 mosquitoes, with sides of mayflies and moths, in an hour, and half their body weight in bugs over two one- to three-hour foraging flights, at dusk and dawn each day.

‘Blind as a bat’ is a misnomer. Bats aren’t blind, but they don’t see well. However, they can navigate and forage in complete darkness using a sort of sonar, making inaudible (to humans) clicks and sensing the direction of the returning echo.

Bats have day roosts in hollow trees or man-made structures such as sheds, barns, or bat boxes. They have larger communal night roosts. Myosis bats, unusual for the species, do not migrate. They hibernate locally, from September to May, seeking out larger, deeper over-winter roosting chambers such as caves and mine shafts where the temperature does not plunge in winter.

This has proved their downfall. Bats are endangered, as an estimated 90 per cent of them have succumbed to “white nose syndrome,” a facial fungus that makes them do strange things like fly outside in the daytime in winter, burning up fat they need to survive. It’s a deadly disease for which crowded conditions in humid caves has proved a perfect – and so far unstoppable – incubator.

Porcupine

Porcupines are long-lived for rodents. Although slow and short sighted, they typically live about 20 years, secure in their prickly defences (porcupine translates as “thorn pig” in Latin).

They are also very misunderstood, saddled with one of the more prevalent myths in nature, alongside that of an Easter Bunny. No, porcupines CANNOT eject or shoot any of their 30,000 hollow-shafted quills.

They can raise their quills menacingly, and should the barbed tips strike a predator, they will stick and detach. When threatened, porcupines can be pro-active, bristling, rattling quills, swinging a quilled tail, even charging backwards. But shooting quills? Never.

While out foraging for roots, shoots and berries day or night, few predators will trouble a porcupine. Two exceptions are martens and fishers, ferocious and fearless mammal foes that have mastered the skill of flipping a porcupine over and attacking its undefended belly.

Blessed with long claws and soft paw pads, porcupines are arboreal – meaning they’re great climbers who spend much of their lives up trees. Clumsily it seems, as they can fall from those trees when stretching for the tenderest buds. This can see them stunned and painfully stabbed with their own quills. Nature mitigates the damage. Porcupines are adept at removing their own embedded quills, which are coated with an antiseptic grease to combat infection.

‘How do porcupines mate?’ you are undoubtedly thinking. Very carefully … no joke. Normally solitary, males battle for a female when her pungent urine markings signal that she is ready to mate.

The victor climbs the female’s tree, stationing himself on a lower branch to keep an eye on her above and a lookout for any rival below. Pitching woo, he sprays her with macho urine, exciting her. She then feels encouraged to climb down to the ground, where she curls her tail up over her back and passionate, if cautious, coupling occurs.

The young, called porcupettes, are born with a full set of soft, pliant quills that stiffen in the air within a few hours.

Wild Turkey

Wild turkeys, while large (17 pounds or more) are much scrawnier than their domestic, supermarket counterparts. They also retain the ability to fly. Butterballs, as the name implies, are bred too fat to achieve lift off.

Wild turkeys are also much more likely to be around past Thanksgiving, though they make a fine meal for predators such as foxes, coyotes, raccoons, skunks, owls, hawks and other raptors at any time of year. The very lucky ones can reach age five.

They’ll be encountered foraging hardwood forests in groups, seeking bugs, berries, snails, salamanders, roots, seeds and such. They’ll also be seen in clearings and along roadsides near woods. And at night, if you look up, you might spot them roosting in groups in the treetops. In any season. They don’t migrate.

Males are Toms, females are hens, immature birds are jakes, and chicks are known as poults. And while beauty is in the eye of the beholder, they’re ugly.

Interestingly ugly. Both sexes have dangling, wrinkly chin flesh (wattles), a plume of scraggly feathers sprouting from their breast (chest beard), knobbly, pocked head, neck and throat flesh (caruncles) and a wormlike protuberance (a snood) dangling from above the beak.

When aroused, a dashing male’s snood engorges with blood, becoming longer and redder as his face becomes whiter. He will gobble (only males do this), drum (make a booming, burbling, sound in his throat), fan his tail, drag his wings along the ground, strut and spit. What female could resist?

American Black Bear

The American black bear (that’s North American; Canada has an abundance) is an opportunistic arboreal omnivore. This means it lives in the forest and will eat almost anything it comes across; the easier the better. Stalking and hunting is usually too much work.

Described as medium-sized, black bears weigh in at about the same as people; males at around 200 pounds, females about 125. But unlike us – well, most of us – their weight varies widely with seasonal diet, often more than doubling in preparation for winter hibernation.

On emerging from their den after winter, black bears are gaunt, having lost a third of their body mass in fat – but not muscle. Through spring they gorge on new shoots. In summer and in season, they’ll eat various berries, in vast quantities. In fall, it’s nuts. And any time at all, anything else edible they amble across – fish, fowl, or alfresco man-made buffets to be found in dumps, campgrounds, picnic areas, bird feeders.

They’re clever, curious and dexterous. A tight jar lid or a latched shed door won’t stop them. They’re also great swimmers, climbers and runners. In fact, they’d do well in an Olympic decathlon, excepting for the javelin throw.

If you encounter a black bear in the woods, it is your fault. Given a choice, black bears avoid humans. If you hike the woods alone, silent, or distracted (ear buds, cell phone) your quiet approach can take one by surprise.

“If so, stop! Don’t make eye contact. Make yourself look bigger. Make noise. Throw things. And back away. Slowly. Don’t run. Don’t play dead.”

Better still, avoid black bear encounters altogether. Hike in groups. Noisy groups. One website recommended singing. The Hills Are A-liiiiiive With The Sound of Muuuuu-sic! Good luck. ❧

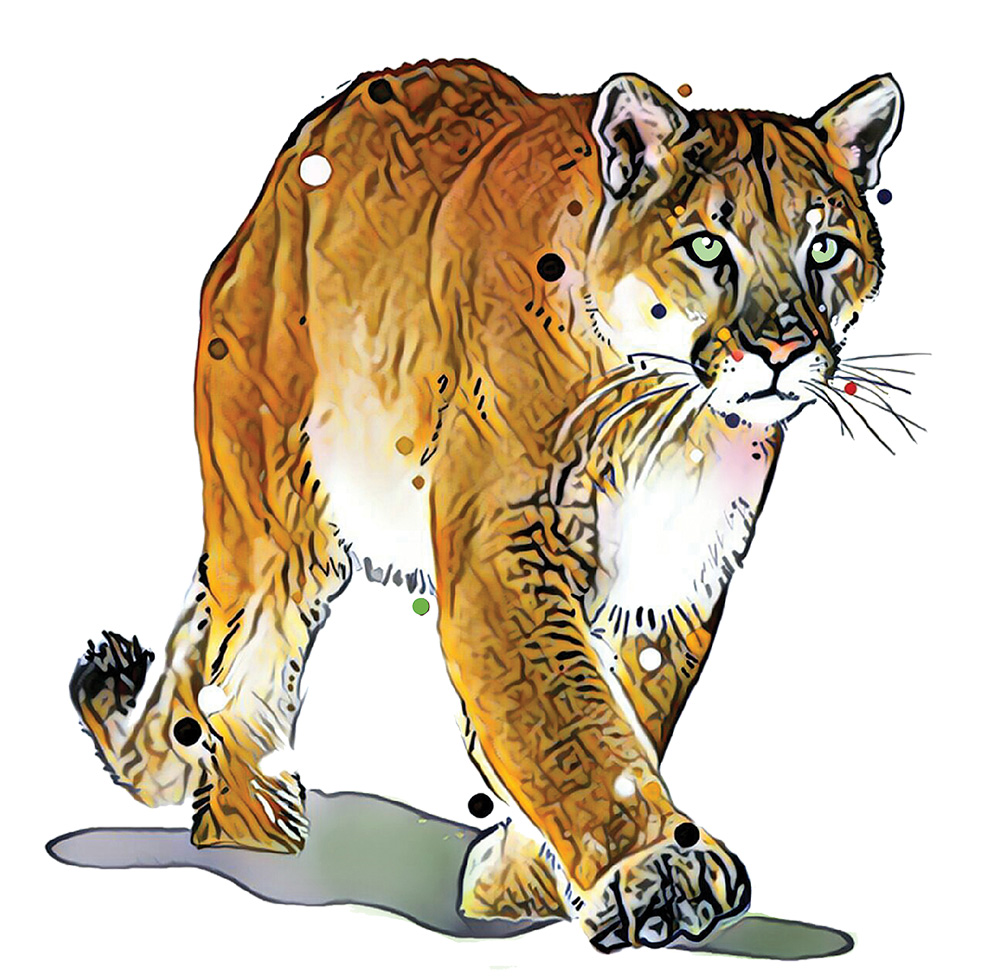

Cougar

Some call them cougars. They’ll answer to puma or mountain lion. They are panthers in Florida, fire cats, catamounts and deer tigers elsewhere. In fact, the cougar has entered The Guinness Book of World Records as the creature with the most names – over 40 in English alone.

The cougar is endangered in Canada, and rare but not unheard of nor unseen around Southern Georgian Bay. They are silent and secretive creatures covering up to 50 kilometres a day over their huge range of deep woods or rocky cliffs, where they have no known enemies.

Cougars avoid humans, and hunt large animals by stealth – deer in particular. They need to eat only once a fortnight, stashing a large kill to return for subsequent feedings, as long as the carcass isn’t poached by bear, stolen by wolves, or scavenged by smaller predators from raccoons to mice.

Sightings are up in our region and not all of them are mis-identifications of bobcat or lynx. The biggest sure identifier is the cougar’s long tail.

Strangely, the cougar is more closely related to the domestic kitty cat than to those in the big cat family. It can’t roar like the big cats. Cougars only hiss and purr, so it’s unknown whether they like their belly rubbed.

The cougar is a majestic and endangered creature. If you should spot one, consider yourself very fortunate – and let someone else settle the belly-rub question.