A community of artists and makers find a portal to paradise.

by Anya Shor // Photography by Anya Shor

Artists are always the Johnny Appleseeds of gentrification.

An American writer said that, but we’re not talking about him. We’re talking about what happens in forgotten neighbourhoods, towns and cities when artists, and generally creative and entrepreneurial young people, come in search of cheap real estate, a like-minded community, creative camaraderie and ample studio space with the kind of windows, light and ceilings that artists’ dreams are made of. Do such places even exist anymore? Developers swoop in like magpies at the first flash of a shiny trinket—or mason jar cocktail bar—to take the artisan out of “artisanal.” But what if such a place is real and lies at the tip of Grey County?

When internationally acclaimed visual artist Kristine Moran and her family parked their RV at Harrison Park in Owen Sound in 2018, the allure was immediate. “Harrison Park has a campground and so we stopped there, and it just felt so comfortable. There was something about that park, but also the whole town—we felt immediately at home.”

After 12 years of living in New York City, followed by extended road trips across the United States and Canada, settling down for Moran required discovering a community of interesting and creative people to call friends, and which would also keep the kids busy. Owen Sound was it.

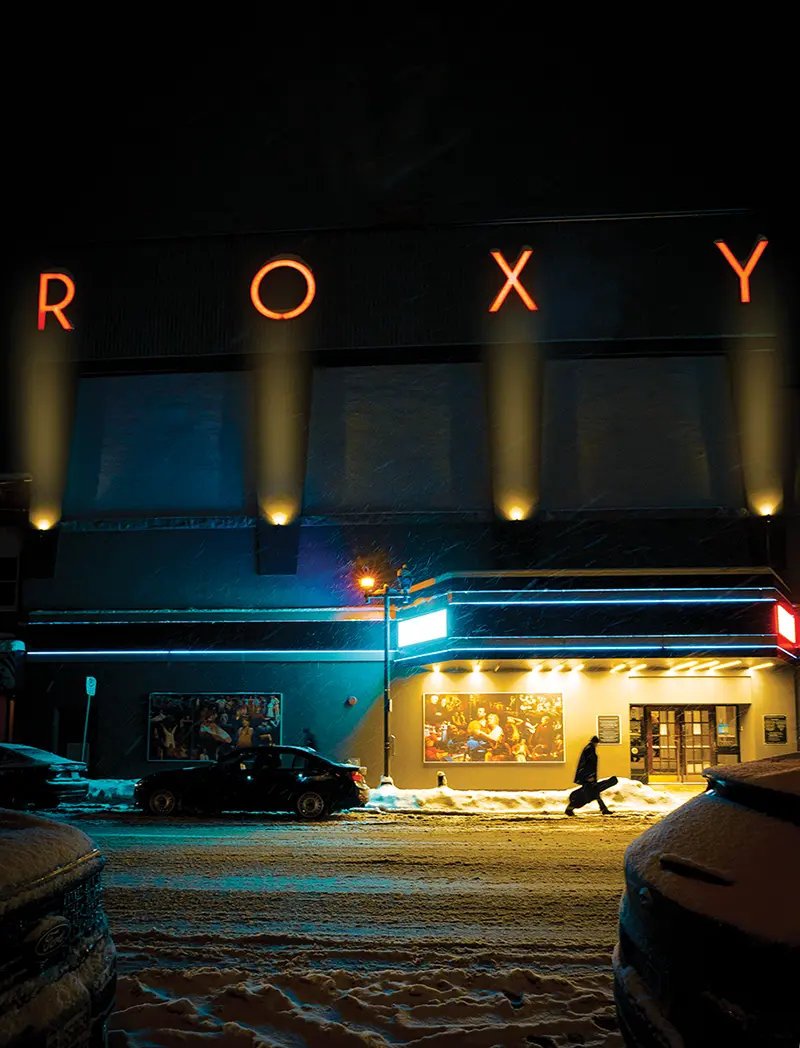

Moran’s older daughter, for example, is actively involved in the community theatre scene at the iconic Roxy Theatre. “It’s a legit 400-seat theatre!” enthuses Moran, “and she has been participating in plays there since the year we moved here. Now she’s doing bigger productions!”

The Roxy Theatre is owned and operated by Owen Sound Little Theatre which is a volunteer-based charitable organization that produces four productions annually, including one musical. Built in 1913, the soft-seat opera house is an important and cherished pillar of the Owen Sound artistic community. “There aren’t a lot of towns this size that have a dedicated theatre company like this one,” Moran says with sincere appreciation.

It didn’t take long for Moran herself to find her community of creative and inspiring peers. “Within a year, I’d met [curator] Heather McLeese from the Tom Thomson gallery, and then someone introduced me to Elly [MacKay], and then I met Coco [Love Alcorn, the Canadian Folk Music Award-winning singer-songwriter], and I was like ‘Oh, there’s culture here!’ There were a lot of things that were really just exactly what we were looking for. Kind of, like, outdoorsy but all this at the same time.” Moran had found her tribe.

One of that tribe is award-winning children’s book author and illustrator Elly MacKay. Originally from Big Bay, just a half-hour north of Owen Sound, MacKay and her young family were living in Kitchener-Waterloo when they decided to make the move back to this region.

“After we had our first child, we decided that we wanted family around, and I’d always wanted to be doing children’s books, so we just moved up here and I started putting together a portfolio,” MacKay recalls. She most recently illustrated a book written by Julie Andrews (yes, that Julie Andrews) and Andrews’ daughter Emma Walton Hamilton. MacKay enjoys the opportunities to travel to bustling metropolises like Toronto and New York City (where her literary agent is), but is very much relieved to call Owen Sound home. “I love our little community and I feel really comfortable. And I feel, because it’s quieter, I can just play. There’s that room and space to play.”

The three friends—Moran, MacKay and Love Alcorn—often gather at Moran’s spacious studio on the upper level of the Harmony Centre, a volunteer-led charity organization dedicated to promoting and building a community hub and concert space. The centre hosts a variety of activities including dance, choir, yoga, karate, meditation, tai chi and music programs. Located in the historic 150-year-old edifice of the former Knox United Church, the centre also provides a slew of artists, musicians and creative organizations with affordable studio and performance space. It’s the kind of architectural landmark that in larger cities, like Toronto, have long since been acquired by real estate developers and converted into “cool” alternative-living condominiums for the seven-figure crowd.

The centre boasts a 700-seat auditorium with a soaring cathedral ceiling, stained glass windows and a stage capable of seating an orchestra. A smaller hall called The Commons seats 160, and features a large white wall suitable for movie projections, space for town gatherings, and an intimacy perfect for acoustic performances such as choirs.

Kristine Moran in her studio at the Harmony Centre.

“… and I was like ‘Oh, there’s culture here!’ There were a lot of things that were really just exactly what we were looking for.”

Jaret Koop, Elly MacKay and Kristine Moran in the auditorium at the Harmony Centre.

“I love our little community and I feel really comfortable. And I feel, because it’s quieter, I can just play. There’s that room and space to play.”

Across from Moran’s studio, on the other side of The Commons, is the office of the Summerfolk festival, now in its 50th year. Jaret Koop assumed the position of festival director in 2020. A musician himself, Koop originally moved to Owen Sound in 2015 after spending most of his life in the GTA. Koop and his family were looking to set down roots in a slower part of the province with access to the outdoors.

“Back in the ‘90s and early 2000s, I used to come through here with different bands. And every time I came through here, all of the parties afterwards…there just seemed to be an incredible amount of musicians and artists,” says Koop. “What I eventually learned was that artists have been moving here since the ‘60s, because it’s one of the last areas in southern Ontario that hasn’t seen the price increases that happened elsewhere. It’s still one of the most affordable places to be in southern Ontario.”

Koop marvels at the concentration of artistic talent and performance in a community of roughly 20,000. “I can go see live music from Tuesday to Saturday almost every week, or go to an open mic, or I can go to one of four or five different art galleries. I’ve never been to a place that has such a high level of very high-level artists and musicians.”

Gentrification is a bit of a dirty word. The process goes something like this—a town or community experiences an economic decline that excludes it from the surrounding growth, leaving it deflated and untouched—and therefore comparatively affordable. Young artists and creatives struggling to meet the inflated demands of busier centres move in and bring with them a new vitality, an electricity, making the area cool and desirable again. Then the developers get a whiff and pounce, condos emerge like mushrooms overnight, a vibrant artistic community gets squeezed out, and the magic fades while the economy grows. It has become a refrain in artistic centres globally—from Queen West in Toronto to Brooklyn, New York. The presence of artists heralds an impending change that is an advantage to the larger community—but a disadvantage to the people who made it possible in the first place.

“There has definitely been that fear here,” Koop says of the gentrification threat. “But it’s a little bit of a forgotten, out-of-the-way place, so it doesn’t really come here the way it comes to other places. When I was telling people that I was moving to Owen Sound, they’d say, ‘Where’s that?’ And I’d say, ‘You know when you’re going to Sauble Beach or to Tobermory to catch the ferry, that town that you turn left in and on the way out you get gas and Tim Hortons? That’s Owen Sound,’” Koop laughs.

“It’s more affordable than other areas—relatively affordable,” says Moran. “And I think that allows for an entrepreneurial spirit, for people to be a little more experimental, like Boon Bakery which is just gluten- and dairy-free product. And all the family-run businesses like The Milk Maid. And we have Casero Kitchen. People do come from all over because it’s become a destination. [But] because of where it’s located, compared to Collingwood or Muskoka, we’re just outside of that enough to be protected, and I think that’s to the benefit of the town.”

“I can go see live music from Tuesday to Saturday almost every week, or go to an open mic, or I can go to one of four or five different art galleries.”

That kind of experimentation is at the heart of chef Zach Keeshig’s culinary practice. Keeshig’s creative, complex and deeply sophisticated approach to progressive Indigenous cuisine has earned him the highest praise from the upper echelons of the culinary world across North America. Keeshig’s newly opened brick-and-mortar iteration of his restaurant Naagan—which began as a unique pop-up dining experience in the breezeway of the Owen Sound Farmers’ Market on weekends—sits like a beacon of warmth in the historic Chicago Building off the town’s main artery and is a destination for serious foodies from across the province and beyond.

Born and raised in Owen Sound, Keeshig left to study and apprentice with the best of the best, including Michael Stadtlander of the acclaimed Eigensinn Farm in Singhampton, with the unwavering intention to bring it all home. “I always wanted to bring what I was doing to where I grew up,” Keeshig says with a definitive confidence. “Growing up, there wasn’t a whole lot of, I don’t want to say fine dining, but, you know, the sort of creative food around this area. So that’s why I took off and trained in different places. But I always wanted to bring it back because this is where my family grew up and this is on traditional Nawash territory. I wanted to showcase my vision, what I envision Indigenous food could be on the progressive side.”

Keeshig employs techniques he honed at Michelin-rated restaurants to his poetic and thoughtful approach to culinary art-making, which includes celebrating regional offerings—from the rocks that adorn the kitchen island at the centre of his cozy 17-seat dining room, to the ingredients foraged from the parks and forests around Owen Sound, and the fish caught fresh from the Bay. But Keeshig remains sensitive to the economic disparity between the local community and those able to travel hundreds of kilometres for a singular elevated dining experience.

“I want to make what I’m doing accessible to everyone. We can have a decent price point where I’m able to pay my staff a living wage and still create good food and local food,” says Keeshig. He believes staying true to oneself is the way to embrace gentrification if, and when, it happens. “I’ve had people come here like, ‘Oh you’re going to outgrow this space in no time,’ and I’m like, ‘No, all I’ve ever wanted is to just cook for 17 people a night.’”

“I always wanted to bring it back because this is where my family grew up and this is on traditional Nawash territory. I wanted to showcase my vision, what I envision Indigenous food could be on the progressive side.”

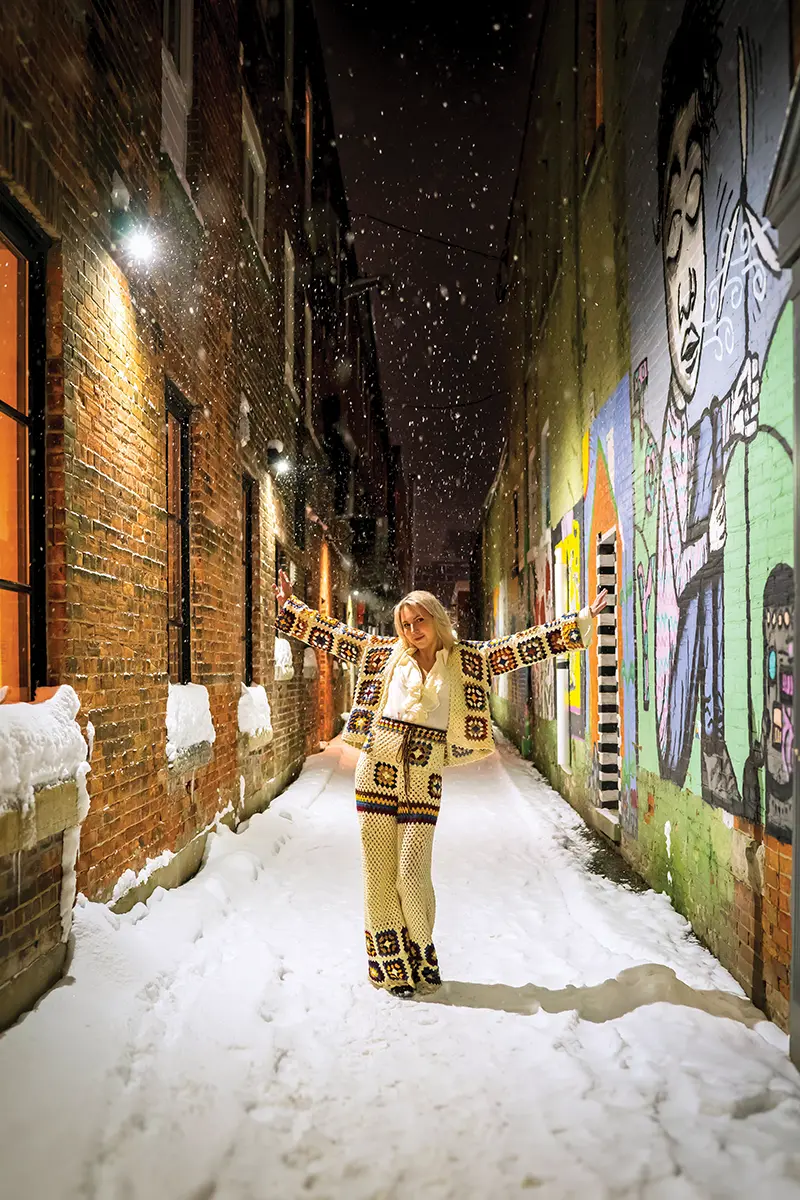

FROM THE TOP The Koodoo Mural in Carney’s Lane, Parkwood Restaurant at Heartwood Concert Hall, Artists’ Alley, The Milk Maid, Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Shanny’s Kitchen.

For young singer-songwriter Gracie Jet, it’s a fine balance between loving the place which nurtured her talent just the way it is, and yearning for the exposure to a wider audience. Born in the south of England, Jet remembers her move to Owen Sound as a child with her family as a culture shock. “I’d never seen snow!” she laughs and quickly adds, “I had a complete childhood here. And I think it really shaped who I was.” Jet recalls an adolescence with endless opportunities to engage in music like guitar lessons and coffee house performances, including at local venue Heartwood Hall.

Jet has an album coming out this spring at a date yet to be announced but says she’ll likely launch it here, at Heartwood, “because that place for me is so significant. It gave me a place where I would go every week on a Tuesday and sing all my original songs. When I do a show there, it’s a surreal moment for me. I remember being up on that stage playing my guitar years and years ago and now I’m up there with a full band, and we sold out a show. It’s a full-circle moment,” she reflects. And while she admits she’d consider moving to a larger city if the opportunity arose, she recognizes that she’d need a plan to sustain herself. For the time being, she’s grateful for the community support. “I can support myself on my own with just my music here.”

Jet suggests, “there’s a magical moment happening here in Owen Sound. You have kind of everything—you have the nightlife, but you also have fields you can run your dog in, and mountains you can climb. It’s like from a movie. I think that’s what draws people in. And while everything is becoming so expensive, I think the way this place is, it makes it a little bit easier to stay here.”

Jet believes the town is growing but in a way that will just keep making it better for the young people who are already here and attract more of the same. “I feel like Owen Sound is really trying to bring back a community where there’s stuff going on downtown, which I think is great. There’s a camaraderie between the entrepreneur, the proprietor, the food people. It’s really trying to create more of a hub where younger people in their mid-20s can go out and have a good time. So it’s about attracting and retaining that younger generation of people that will stay and continue to grow with the town.”

“There’s a magical moment happening here in Owen Sound. You have kind of everything—you have the nightlife, but you also have fields you can run your dog in, and mountains you can climb. It’s like from a movie.”

Where there are songwriters, there are poets.Rebecca Diem, Owen Sound’s poet laureate for 2024/2025, recently moved back to the area with her young family. Elizabeth Zetlin, the inaugural poet laureate of 2007/2008, originally fled Norfolk, Virginia, with her then-recently drafted young husband to Canada in 1969. Zetlin eventually found herself spending increasing time in the Grey-Bruce area until a job offer at the Tom Thomson Gallery solidified her move to Owen Sound in 1995.

“What drew you to the area was affordability, and the young people I speak to now, like Rebecca, it’s the same story. Affordability is what’s drawing them to the area, but what affordability meant and what it means now are two very, very different things,” muses Zetlin.

The spirit of creativity remains the same. “There was a writing community, but it wasn’t really visible so much,” recalls Zetlin. “So for me, it [the laureateship] gave me a license to create, in a kind of official way, and to share what I was doing with the whole Bruce and Grey. So I drove all across [the region] and I was part of a national Random Acts of Poetry initiative. Every time I did a reading, I would give someone a poetry book. And it was amazing! The reception! People were just hungry for poetry.”

For Diem, returning home meant connecting with a community of poets in a meaningful way that’s not offered to a young writer in a city like Toronto. “In Toronto, you throw a rock and hit a poet, but up here there’s an intergenerational community of artists, and that’s been such an incredible experience,” she says. The mutual admiration between the two women is evident as Diem adds, “Getting to know Liz and getting to talk to her and hear these stories, I just feel like I’m constantly in the presence of greatness and it’s just motivating and it makes me feel more fearless in my own work.”

It sounds utopian and nostalgic. For Moran, whose work can be described as gestural, colourist abstracts that seem to want to capture a sense of an elusive utopia—that corner of a garden in which one might experience a momentary and fleeting sensation of stepping through a paradisiacal portal—Owen Sound has brought that quest close to home. She speaks about spaces that are like “secret gardens, the kind of space you walk into, and it feels a little magical, but also not very many people know about it.” Koop wryly suggests “There’s an aspect to Owen Sound that we would like to do great things, but we would also like to remain hidden.” Perhaps this thriving community of artists and makers have truly found an artist’s paradise at the end of the earth. Only time will tell.