by Dianne Rinehart //

Multimedia artist and musician Kyle Haight proves one man’s trash is another man’s treasure—and a message in a bottle about the precarious health of our world.

Collingwood artist and musician Kyle Haight’s farm home is perfectly positioned.

Collingwood artist and musician Kyle Haight’s farm home is perfectly positioned. It’s nestled in the nature that inspires his work, within spitting distance of Blue Mountain, where he indulges his passion for snowboarding. And, most importantly, it’s near the municipal dump.

Yes, you read that correctly.

The dump full of junk, plus the odd dumpster outside of homes that are being renovated around town, could be described as Haight’s muses. (“You won’t believe what people throw out,” Haight says.) That’s where he finds inspiration from the discarded pieces of furniture, plastic, wiring, athletic gear, goggles, musical instruments, coils, dumbbells, skis, drum skins, stuffed toys, medals, hockey pads, keys, pieces of wood and, oh, the cardboard from a packing box for a hot water tank, that figure so predominantly in his sculptures and paintings.

But don’t think for a moment that Haight is just fashioning waste into wants. “I only want to work with something that won’t be used again,” he says. If he finds something in working or mint condition, he uses it or gives it away.

Does his artistic impulse stem from a strong sense of environmentalism? Is it a message about a disposable society? Or does it originate from the “stark poverty” he grew up in, where, perhaps, he fine-tuned his thoughts about want versus need?

Haight says he is genuinely “appalled at the way we go about not caring what we throw away.

“The only thing we need is food, shelter, and medical assistance. Anything else is a want,” is how he explains his message.

Haight says he has been accused by critics of “virtue signalling” with his work.

If it is that, this labour-intensive work that sees him digging around dumps, nevermind spending years fashioning mobile sculptures from his finds, is a very hard, unpalatable way to do that.

Up close, each piece of sculpture looks like a mini junkyard. But stand back, and you see that his sculptures are designed to be mobile, while standing upright—no matter the human, bird, animal, bug or dinosaur motion that they are depicting.

Haight, who snowboards at Blue with his partner Mel Sheridan and 12-year-old daughter, Scarlett, says he grew up skateboarding.

“You never give up,” he says, comparing that experience to the hours and hours—nay, years!—he puts into fashioning his sculptures. “Finishing is the goal.”

Take The Scrap Skiers, for example. The sculpture is a life-sized grouping of a family of four, each in motion. Haight is still working on finding the right pieces of junk to create the details of the faces, but everything else in this crazy melange of cast-offs manages to give the feeling that they are going to pop on the ski lift beside you some day.

It’s quite disturbing, enlightening, and entertaining to see Haight create something so futuristic looking—artificial intelligence skiers, anyone? – from old and decrepit detritus from the past.

Or consider his grouping of sculptures called Guitar Birds, that he refers to as his “Avian Oracles.” He worked on them for five years. They are made from guitars and are balanced on stands and speak to two of his passions: music and birds.

Birds are the closest thing to dinosaurs, he says, brandishing a National Geographic magazine from 2018 that has an article called “Why Birds Matter,” written by the author Jonathan Franzen.

“It’s not just what they do for the environment,” the article says, “it’s what they do for our souls…and why we really can’t live without them.”

Haight doesn’t want birds to meet the fate of the dinosaurs, one of which he has created from the discards of consumerism that he calls Wantasaurus. The huge sculpture, set up on an edge of the farmland that surrounds his home and studio, appears to be looking out across the horizon for a mate. Or for danger. It’s unclear.

But what is clear by its name is that Haight, through his art, is exploring the cast-offs from society—even those, like our endangered birds, that are still alive.

It’s no surprise that his latest exhibition, at the L.E. Shore Memorial Gallery in Thornbury last fall, was named “Divergence & Intersection” or that a 2015 showing at the Durham Art Gallery was called “Harmonic Chaos.”

The words seem to capture the chaos of the heaps of garbage around us, a fear of the future, and a warning about the fragility of life, as his sculptures do.

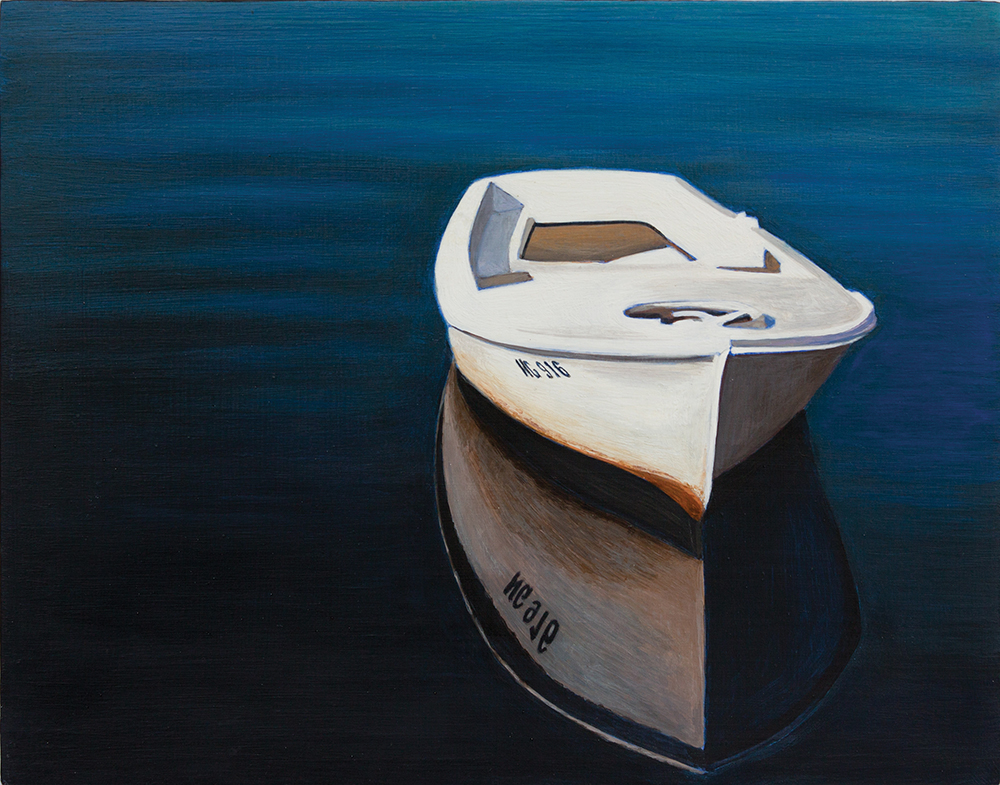

And then there are his paintings, mostly created on huge circular canvases, which give off a very different vibe than his sculptures. They don’t slap you in the face with a clear warning. Instead, the series of paintings of vessels, he calls “Tesalonian Ships,” are moody, surreal, and appear to be seen through veils of light.

He says the vessels are floating on a “watery surface.” But a viewer might see them as the spaceships humans could use to escape from environmental chaos to another world.

And Haight, who graduated with honours from Georgian College in Barrie, is no less passionate about his music than his art. He started as a drummer but now focuses on playing bass guitar.

There is a distinct and defined crossover of his musicality with his paintings and work. Indeed, many of his sculptures are made with pieces of instruments. The wings on his Guitar Birds, in fact, are made with discarded drum skins.

As with his art, Haight seems surprised with where and how far he goes in his music. He wrote a song called “The River.” At the time he wrote it, he says he didn’t know what it was about.

“Then a friend finished the vocals, and I realized it was about Justin,” he says of his brother who died of a fentanyl overdose right in front of him in the fall of 2018.

“I tried to resuscitate him.”

Justin loved fishing and turned to it to try and get straight, says Haight. The song was how Haight dealt with his brother’s addiction and death.

“Results of the lighting were shown

From the fire and the birds have flown.”

It’s no wonder Haight is so productive on so many fronts. He has found the perfect home for an artist and his family: a farmhouse surrounded by fields, yet close enough to Collingwood that he can ride his bike to town. His studio is an old milking barn. It stores his paintings and sculptures, and he has built a sound booth and a stage, both set up for the practices he holds with his six-piece funk/rock band What’z What and other music sessions he hosts.

In front of the stage are tables made from huge old spools he found that once held wire.

Turning junk into art and useful furnishings, it seems, never stops.

Then there is the area he has created for his painterly passion. On a table are assorted paints and brushes and other tools he uses to create his works. His now-retired father, he says, was a sign painter and some of these tools are his.

Right at that spot in this huge structure is a huge barn door. It is open so he can look out on the nature that inspires his works of art, which seem to be the antipathy of the natural world.

Is that the point?

Haight doesn’t earn a living from his art and music, yet. In the meantime, he says, he loves his job as a house painter. He only works enough to make money to pay the bills, to give him the freedom to get back to his sculptures, paintings, and music.

“I work to get back to my purpose, creating things, writing songs, making music.”

Anything less would be a waste of talent, right?