Winter’s icy grip gave the Bay a sublime beauty that’s becoming increasingly rare to see.

By Willy Waterton // Photography by Willy Waterton

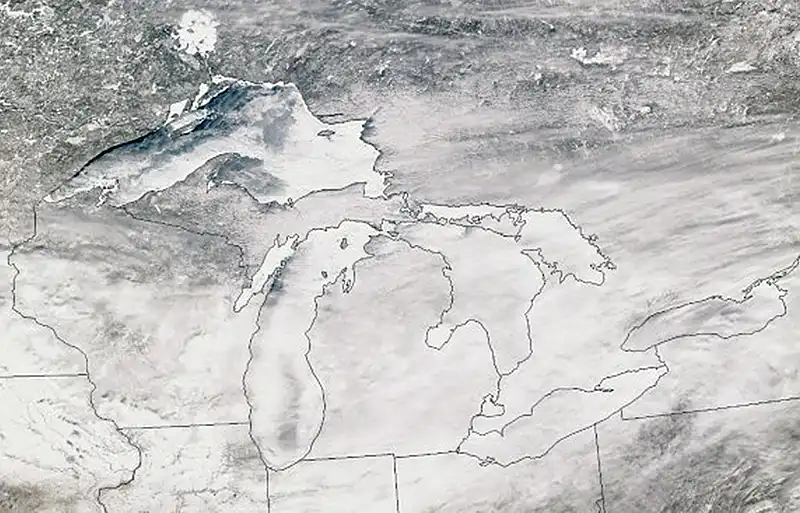

It was cold! How cold? Cold enough to freeze over 92 percent of the Great Lakes surface ice. And there I was on a beautiful, sunny and crisp -20 C February day, skiing along the Georgian Bay shore of Bruce Peninsula National Park to photograph a sea cave.

Believe it or not, I was the only person in the park. It was only 2014, not that long ago. But it was before COVID and social media “discovery” of the Saugeen Bruce Peninsula. Very few people ventured to the park in winter. The closed Cyprus Lake office and empty parking lot blanketed with a foot of fresh powder greeted me as I laced up my backcountry ski boots and pulled on an extra layer of clothing.

Normally my wife would have accompanied me on this adventure but she was off chasing monarch butterflies in Mexico. Because of the isolation, cold and possibly dangerous ice, I texted our daughter in Ottawa to ask her to notify rescue if I didn’t send her a text every 30 minutes.

Reaching the shoreline, I viewed a field of ice as far as you could see, surrounding Bears Rump Island and Flowerpot Island to the north and Lonely Island to the northeast.

Confident the ice was safe, I worked my way along the coast, over pressure ridges and among icebergs, mesmerized by the ice-covered cliffs glistening in the morning light. Once at the sea cave, I cautiously entered and was met by a magical world of icicles—a result of water freezing as it dripped from the ceiling.

It was then I got scared. Ice “works,” expanding and contracting with currents, wind and temperature change, and “speaks” with grinding noises and occasional booms as it releases pressure. It was the boom that scared me. If that pressure release had happened to be where I was standing, the ice could have opened up, exposing me to the nine to 15 metres of frigid water below. However, with such a cold winter, the depth of ice in the cave was close to a metre thick, so it seemed irrational to worry. I stayed long enough to take this photograph with myself for scale, using a fisheye lens on a tripod-mounted camera with a remote shutter release (hence all the footprints in the foreground from setting everything up).

Those days are mostly gone. Ice coverage data collected since 1973 by the NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory shows the ice coverage growth cycle is declining annually by 22 percent primarily because of global warming. There are cold spells but not the extended cold weather that forms thick, solid ice. In February 2021, two hikers had to be rescued by OPP helicopter from ice floes near the Grotto in Bruce Peninsula National Park when the shoreline ice that they were walking on separated and drifted three kilometres offshore.

After taking the ice cave photograph, I scurried back to the shore and was soon texting our relieved daughter of my safe return to terra firma.