Will the More Homes Built Faster Act live up to its name and solve our housing crisis?

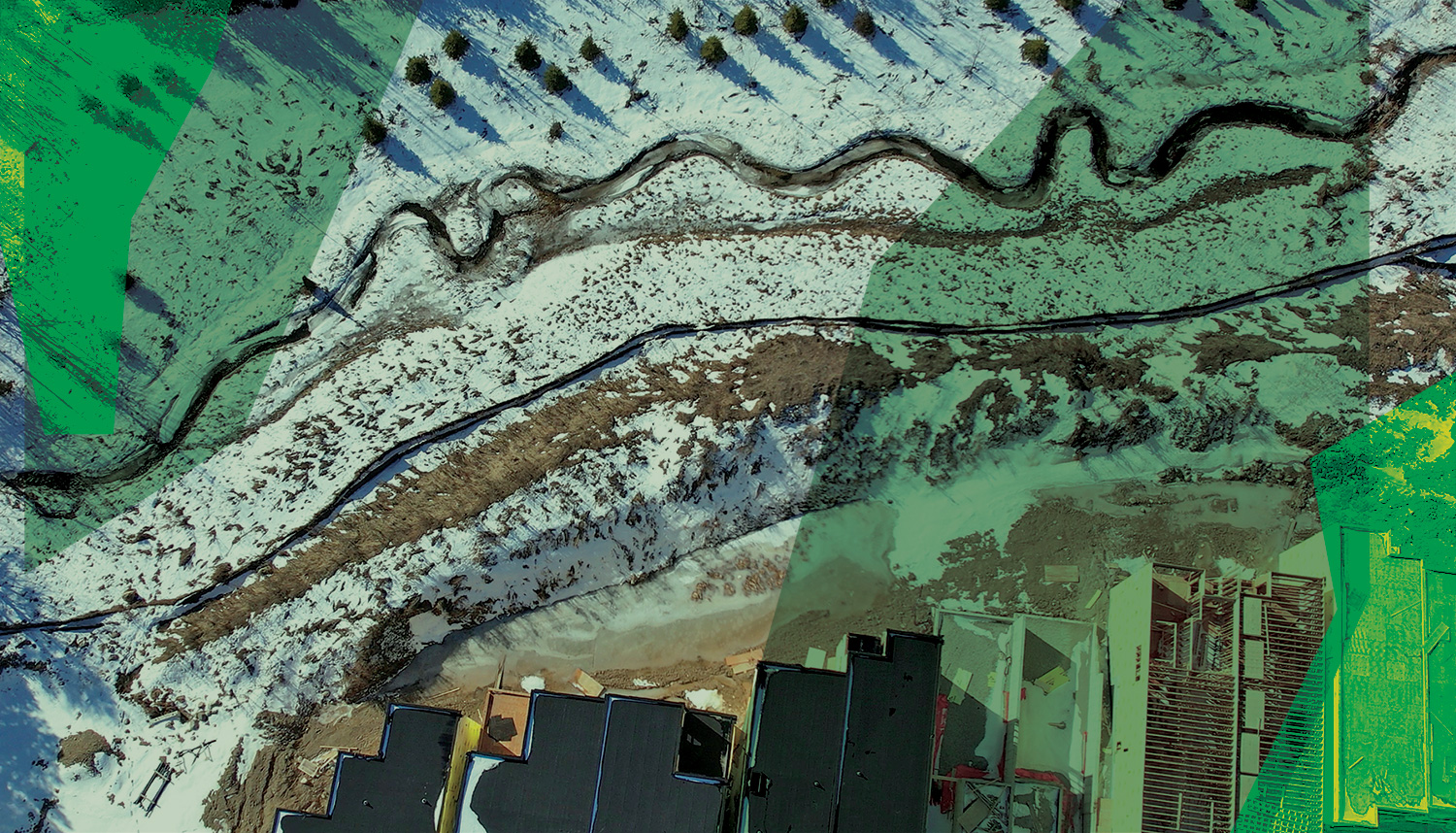

by Trent Gow // Photography by Roger Klein

“We believe that affordable housing is the greatest challenge currently affecting the sustainability of municipalities in our region,” says Rosalyn Morrison, chair of The Institute of Southern Georgian Bay, a collaborative “think and do” tank that aims to create a healthy, caring community while considering a wide range of social, environmental and economic factors. The Institute’s Regional Housing Task Force recently estimated that nine out of 10 families living here today could not afford to buy their first home in this region.

Faced with higher interest rates and persistent inflation, the housing situation for young families is deteriorating and there’s increasing political pressure at all levels of government to find solutions. In response, late last year the Ford government took dramatic action and quickly passed comprehensive legislation officially named Bill 23, More Homes Built Faster Act. Just 34 days after introduction, the legislation received royal assent. Its ambitious bottom line goal is to build 1.5 million homes over 10 years. Coincidentally that happens to be twice the number of homes that were built in the province over the previous decade, according to data compiled by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

Speaking at the Rural Ontario Municipalities Association conference in January, Premier Ford said the housing crisis was decades in the making.

“Previous governments refused to build the housing we needed. With our population expected to grow by over three million people in the next decade, we need more homes built faster. It’s simple economics, it’s supply and demand, we need to work together to build homes to make home ownership more attainable for people.”

To do so, Bill 23 brought seismic changes to the way housing construction is regulated in the province. Reaction was fast, and mostly furious.

Chopping Red Tape

Paramount in the legislation are multiple sweeping measures to accelerate the building of more houses by speeding up approval times and eliminating red tape. Certainly the residential construction industry is enthusiastic.

According to David Wilkes, president of the Building Industry and Land Development Association, “Bill 23 is the big, bold housing plan Ontario needs. Currently, it simply takes too long to get building approvals and it is too difficult to add gentle density.”

But will these new houses be affordable? That’s the telling question asked by Ted McMeekin, former Liberal minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing. “There is no evidence that Bill 23 will bring the alleged benefit the province claims, least of all an influx of ‘affordable’ housing,” McMeekin said.

McMeekin is one of a long list of critics, including Ontario municipalities, conservation authorities, environmentalists and social housing advocates, who have serious issues with the legislation. Locally, Collingwood Mayor Yvonne Hamlin fears the bill will have “serious, unintended negative consequences.”

“We believe that affordable housing is the greatest challenge currently affecting the sustainability of municipalities in our region.”

Rosalyn Morrison,

chair of The Institute of Southern Georgian Bay

Inadequate Consultation

One frequently expressed concern is the perceived failure by the Ontario government to consult sufficiently, particularly considering the wide extent of Bill 23’s sweeping changes. The legislation was rushed through with only 34 days between introduction and royal assent, at a fragile juncture when all Ontario municipalities were changing over to newly elected councils. The Chiefs of Ontario, a group representing First Nations across the province, called the truncated consultation period and lack of formal outreach to them “an unacceptable abuse of power.”

Greenbelt Uproar

Much attention has been focused on changes which are seen by critics as diluting the effectiveness of Ontario’s Greenbelt to limit development and protect farmland, forests, wetlands and watersheds in southern Ontario.

Bill 23 removed from the Greenbelt 15 areas of land totalling approximately 7,400 acres at the edges of the GTA. (None are in Simcoe County.) These redesignated areas can now be the sites for the construction of up to 50,000 houses, beginning no later than 2025. But, the prominent Alliance for a Livable Ontario, which was established spontaneously by many prominent former municipal leaders and municipalities to combat Bill 23, rejects the need for these measures.

The Alliance commissioned a report to review existing housing unit capacity on lands in the Greater Golden Horseshoe, which concluded, “Ontario has enough approved land to build more than two million homes by 2031 without developing the Greenbelt.”

The removal from the Greenbelt was offset by the addition of a 9,400-acre block near the Town of Erin. But this is of little solace to environmentalists. According to the Greenbelt West Coalition, a group of farmers, professionals and community leaders in southwestern Ontario, the addition is insignificant relative to the much larger expansion of the Greenbelt across the Grand River watershed that they believe is urgently required.

“How do we plan the roads, solid waste management systems and natural heritage systems we will need?”

Nathan Westendorp,

Simcoe County director of planning

Conservation Authority Changes

According to Conservation Ontario, which represents Ontario’s 36 conservation authorities, Bill 23 weakens conservation authorities’ ability to protect people and property from natural hazards; reduces critical natural infrastructure like wetlands and greenspaces; and shifts those responsibilities onto municipalities.

“Conservation authorities work on a watershed basis,” Mariane McLeod said in a media release last November, as Collingwood’s then-deputy mayor and chair of the Nottawasaga Valley Conservation Authority (NVCA). “If municipalities are directed to take on this task, we just don’t have the staff or expertise in water resources engineering, environmental planning and regulatory compliance…to do that. We need to keep all hazard-related responsibilities with NVCA.”

Carl Michener, president of the Blue Mountain Watershed Trust, is blunt. He asks, “What recourse do we the people have to protect our environment and our ability to house ourselves in the face of such damaging legislation?”

An End to Upper-Tier Planning

Bill 23 removes the role and function of the Simcoe County Planning Department from the housing development approvals process. Nathan Westendorp, the county’s director of planning, says, “While this may lead to building more homes, they may be in communities that no one will want to live in. Removal of this role may in fact slow down, and even prevent critical social housing projects from being completed.” Without this important responsibility, Westendorp asks, “How do we plan the roads, solid waste management systems and natural heritage systems we will need?”

Reduced Municipal Charges and Fees

Bill 23 exempts developers who build “affordable” or attainable housing units from paying some development charges, parkland dedication fees and community benefit charges. The Association of Municipalities of Ontario (AMO) estimates that these measures will result in $5.1 billion in lost revenues across municipalities over a nine-year span, equating to $555 million lost annually.

Simcoe County has calculated that it will lose at least $175 million over the next 10 to 15 years. Collingwood Mayor Hamlin weighs in, “The province has asked municipalities to encourage development, but taken away our power to help fund this growth. ‘Growth pays for growth’ has always been the mantra—it is unfair to ask property taxpayers to pay even more to cover these costs.”

Our Local MPP Responds

Brian Saunderson, MPP for Simcoe-Grey, has much in his background to expect a balanced view in assessing the impacts of Bill 23. As the former mayor of Collingwood and Simcoe County councillor, he was on the other side of the table and was actively involved in promoting and achieving social housing solutions at the county level. But he is also the local representative of the Ford government that passed Bill 23 and is a strong proponent for the “necessity” of implementing its initiatives. So how does he square the circle?

Responding to accusations of inadequate consultation, Saunderson states that significant revisions were made to Bill 23 in response to standing committee deliberations and public input. He also points out that the bill grew out of the findings of the Housing Affordability Task Force Report released in February 2022, which itself received extensive public comment

“I see this as a necessary investment by the municipalities in the sustainability and viability of their communities.”

Brian Saunderson, MPP for Simcoe-Grey

Saunderson pushes back at the bill’s many environmental critics. He asserts that conservation authorities are not being gutted and will continue to be strong and resilient. He says their mandates are being refocused on the core sustainability and stewardship responsibilities they have exercised so well since 1946, as strengthened after Hurricane Hazel in 1954.

“Wetlands will continue to be strongly protected by this and other Ontario legislation. We have no intention of permitting housing on wetlands, nor will any prime Grade A agricultural land be converted,” he states.

Nor does Saunderson agree that diminished municipal development charges and related fees are counterproductive, pointing out that even if the changes do cost municipalities $555 million annually as AMO estimates, that would represent less than one percent of their total municipal revenues.

“I see this as a necessary investment by the municipalities in the sustainability and viability of their communities,” he says. “Last year Ontario municipalities had about $9 billion in unspent development charges reserves. That’s why we are asking municipalities to either spend or allocate at least 60 percent of their reserve balances each year.”

The MPP acknowledges that his former Simcoe County council colleagues have concerns about the county’s redesignation as an upper-tier municipality without planning responsibilities.

However, he states, “I believe that this removal is essential to streamline the approval process and eliminate duplication. Two-tier approvals are a redundancy that takes precious time and adds thousands of dollars to the cost of a new home. I have full confidence that the lower-tier municipalities across Simcoe and Grey counties have the bandwidth to manage the approval process efficiently and effectively.”

Saunderson asserts, “Bill 23 is one part of a suite of legislative changes introduced by this government to meet the housing crisis head-on. We are taking the necessary steps to address what is quickly becoming a humanitarian crisis in our province.”

The Way Forward

After all of the give and take, are we any further ahead? Will the measures of Bill 23 result in significantly more homes being built, especially for those who need them most? Or, as many critics fear, will unintended negative consequences just add to the damage? It’s an empirical question and only time will tell. But time is not the friend of those in urgent need of affordable housing.

However effective the legislation may be, it’s clearly not the whole solution. Many challenging elements of our complex housing problem are beyond its scope. Locally, the leadership of The Institute of Southern Georgian Bay can help fill this gap, drawing particularly on the insight gained from its two recent comprehensive affordable housing initiatives. Both its Regional Housing Task Force: South Georgian Bay report and Southern Georgian Bay Affordable Housing Toolkit look at affordable housing solutions through a unique regional lens focused on the Town of The Blue Mountains, Clearview, Collingwood, Meaford and Wasaga Beach.

These reports underscore the need for a cross-sectoral, collaborative approach to finding the full range of housing solutions. This means connecting, sharing knowledge and fostering coordination among all three orders of government, the private sector, community partners and local housing advocacy groups to incentivize and support the creation of affordable housing in the many forms it must take.

In the words of Institute chair Morrison, “The future economic growth, development and wellbeing of our SGB communities depend on this.”