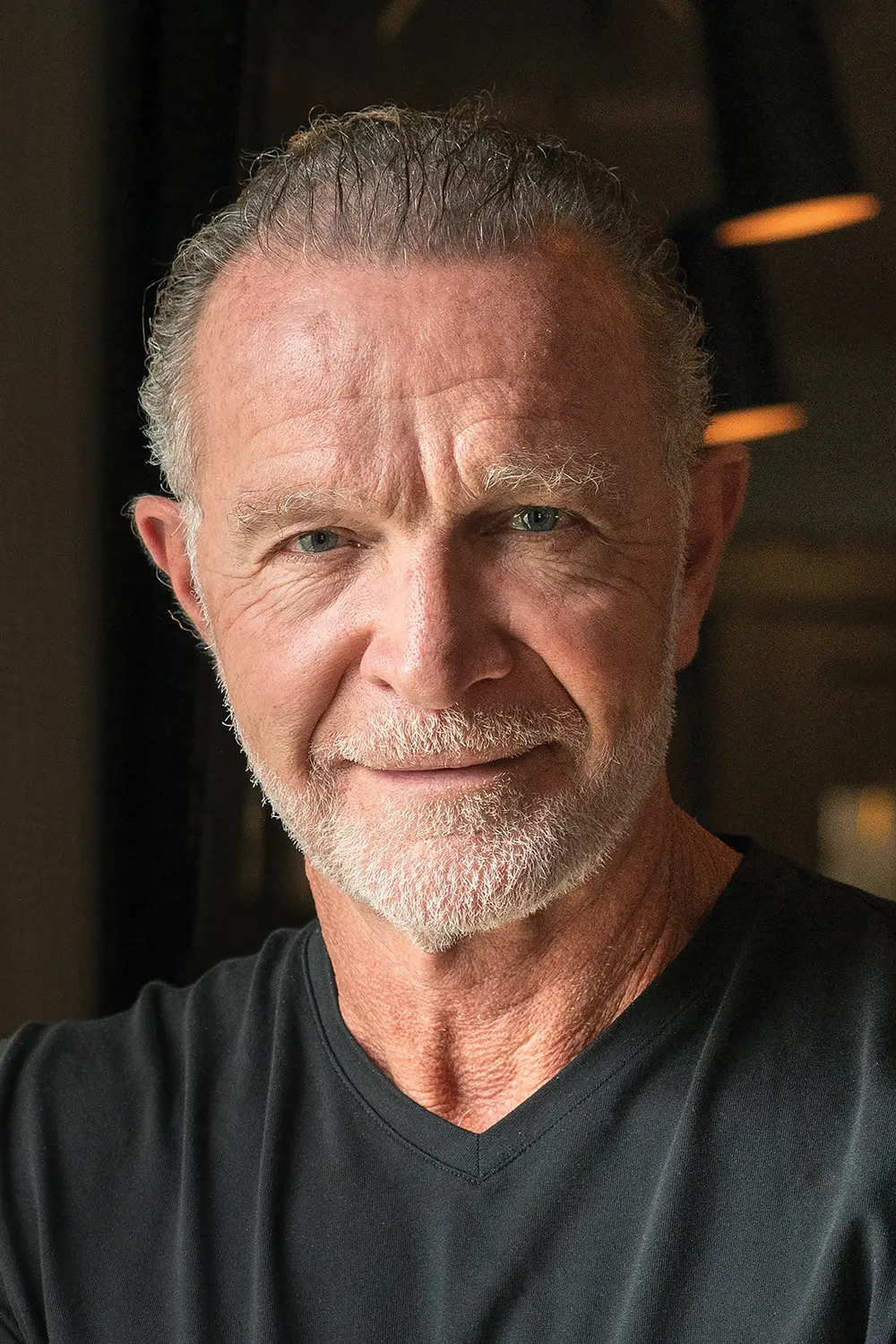

The eminent chef behind Thornbury’s The Port Tavern meditates on success, career, and the inclination to never stop working.

by Natalie Goldenberg-Fife // photography by Anya Shor

For over four decades, Mark McEwan, chef, businessman, television star and restaurateur, has topped the list of Canada’s culinary success stories.

At 67, with five restaurants, two gourmet grocery stores, a booming catering business earning many millions of dollars a year, 300 employees, a bounceback from a couple of business failures, and an 11-year stint as a head judge on the Food Network’s Top Chef Canada, McEwan says he has no interest in retirement.

“I’m not a young man but I feel young. I’m still very happy to work and hopefully I’ll grow old gracefully. Retirement is overblown. I like to have something that gets you out of bed in the morning,” says McEwan.

In July, he opened a country-style tavern, The Port Tavern in Thornbury—his eighth restaurant opening and second in Grey County.

“This location has failed as a restaurant for 20 years and I’ve watched every iteration of that,” says McEwan, who made a home in the region when he surprised his wife, Roxanne, with a property on the water after they joined the Georgian Peaks Ski Club in 1997. (Mark calls Roxanne the family’s COO, and they both recount the same love story—simultaneously falling for each other after passing one another for the first time in the hall of the Constellation Hotel 43 years ago, when Mark was a 25-year-old sous-chef and she, a 22-year-old waitress. )

“We watched Thornbury go from a ski town, with very little going on in the shoulder season, to a bustling year-round destination. Everything was torn out and we built a new bar and refurbished the entire place. All the blue, grey, and wood decor you see is new,” McEwan says of The Port. “We wanted it to feel both comfortable and fancy. As winter approaches, we’ll do cheese fondue and have a fire going. The patio seats 110.”

On the Canada Day opening weekend, The Port served over 455 people.

“Thornbury always lacked a proper patio with a view,” McEwan says. “It lacked a place to go and enjoy cocktails. You can come to The Port for confit lettuce wraps, snails, tuna tartare, gravlax, oysters. We have great burgers, plenty of sandwiches. You don’t necessarily have to sit down for a steak, but you can do that too.”

Beverage-wise, The Port has a modest wine list of 25-plus crowd-pleasing, affordable new- and old-world wines from around the globe. “You can get a good red without having to spend a couple of hundred dollars and our cocktails are more classic than funky. We are supportive of local products, especially beer and cider,” McEwan says.

“Thornbury always lacked a proper patio with a view,” McEwan says. “It lacked a place to go and enjoy cocktails.”

Eight years ago, McEwan opened Fabbrica Thornbury, an Italian restaurant with 68 seats inside and a 50-seat seasonal patio. Fabbrica TD Centre, located in Toronto’s Path, is an abbreviated version that concentrates on Monday-to-Friday quick-service lunches and early dinners, with a focus on Roman pizzas.

All McEwan’s other establishments have also been in the hustle and bustle of Toronto. From the iconic Bymark, where Bay Street goes to eat, drink and party, to the ONE Restaurant in Yorkville’s five-star Hazelton hotel, which earned upwards of $15 million a year and sometimes served a thousand people on a busy Saturday. McEwan restaurants are like multi-platinum record hits.

ONE is no longer in the picture, which McEwan says is “bittersweet,” but after a 16-year run, he says the new owners of the hotel made him an offer he couldn’t refuse.

Why do his restaurants have such lucrative longevity? Probably because a word that drives McEwan’s form of never-say-no hospitality is often.

“‘Often’, that’s the key word,” explains McEwan. “I want people to come to my restaurants often. Come for drinks and sit at the bar. Have an appetizer. Come for a family birthday. Come for date night. Come have a sandwich for lunch and then come back for caviar and martinis at the bar for dinner. When you have a place that’s flexible and a menu that’s flexible, you are successful. My clients have said to me, ‘You know how many times I was in this month according to my Visa statement?’ Those are the conversations I like to have.

We see people often and if we screw up, we make it right. The client always wins unless you are a complete idiot.”

“Am I lucky? I would say yes,” McEwan accounts. “But I would also say, you make your own life.”

Ethics, blunt wisdom, and a profound understanding of human behaviour, business and hospitality—along with a rugged, classic style of food and an ironclad work code—have chiselled McEwan’s career.

Yet his entrepreneurship hasn’t always looked like a beer commercial. A very public filing for creditor protection and financial restructuring of his businesses came in 2021 when McEwan closed down two underperforming stores in the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic: a 17,000-square-foot grocery/grab-and-go store at Yonge and Bloor in Toronto and a Fabbrica location at Don Mills.

“When I closed the store at Yonge and Bloor, that was, for me, a monumental failure. I thought the store was going to be the easiest thing I ever did. I looked at the demographic around it, filled with 100 condominium buildings, and thought I never had density like this,” McEwan recalls. “But I was wrong on everything. The demographic was completely different than I thought. The nut of wisdom is to always second-guess yourself and never fall in love with a deal. Some of the most successful people in the world have failed many times. I look at the totality of everything and try not to beat myself up about it.”

Over the course of many conversations with McEwan, his son Eric (COO of the McEwan Group), his wife Roxanne, and current and former employees, you get the sense that McEwan is the type of leader that doesn’t get made too often.

“The reason I’ve stuck around so long is, he leaves me alone to run the restaurant/business,” says Brooke McDougall, McEwan’s executive chef at Bymark who has been with him for over 28 years.

Serendipitously, McDougall met McEwan as a 24-year-old sous-chef in Thornbury at the now defunct Carriages, a restaurant in a Victorian house by the Beaver River.

McDougall was introduced to “Mark” (how everyone, including McEwan’s son Eric, refers to him) by a regular client at North 44, McEwan’s flagship upscale eatery on Yonge Street that had a 28-year reign feeding and entertaining Toronto’s elite.

“We got to chatting and Mark said, ‘Look me up if you ever move to Toronto.’ A little while later, I knocked on his door at North 44 and he said, ‘OK, start on this day,’ and that was it,” says McDougall.

McDougall moved up the ranks at North 44, learning butchery from McEwan along with how to run a cost-effective restaurant.

“I’m not a young man but I feel young. I’m still very happy to work and hopefully I’ll grow old gracefully. Retirement is overblown. I like to have something that gets you out of bed in the morning,” says McEwan.

“Seven years later when we opened Bymark, he said, ‘Here are the keys to run the restaurant.’ I’ve always taken care of it like it was my own,” says McDougall.

“I look for people who think independently, are secure, focused on the game, and don’t come to work with a lot of baggage. As an employee, you make yourself invaluable by being valuable,” McEwan says. “If the attitude is there and the actual technical training is not, I’m OK with that. If you are helpful, thoughtful, and look out for others, you will instantly rise to the top. Those are the people I look for and they come in all shapes and sizes and from all different places.

“I’ve had lots of people come through my kitchens or front-of-the-house where they didn’t know anything and they left to become big chefs out in the industry and I’ve also got a lot of people that have been with me over 20 years. Minh Chanh-Ly is my longest-serving employee who has been with me at Bymark for 35 years now,” McEwan says.

“Minh arrived in Canada on a boat from Vietnam,” recounts Roxanne. “Minh’s just an amazing guy, which Mark recognized and supported him from dishwasher to the best prep man in the company. He’s helped lots of people over the years.”

“Am I lucky? I would say yes,” McEwan accounts. “But I would also say, you make your own life. You have to be able to identify opportunities and know when to jump and when not to. I’ve never looked for a job in my life. I knew how to work. I saw snow come down so I shovelled driveways, I made money. I saw grass grow, I cut lawns, I made money. I’ve worked my whole life.”

Rugged Classics

The Port is meant to be an approachable, casual restaurant where you can eat on a scale from a smash burger and onion rings to a dry-aged steak and house-made gravlax. In winter, come for après ski and have escargot, oysters, steak tartare and cheese fondue while watching the fire.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: Steak tartare and house-cured organic salmon gravlax. Grilled tuna niçoise. Oysters with mignonette and citrus. Roasted BBQ-spiced pickerel and the six-ounce tavern dry-aged steak burger with onion rings.