Our wetlands are getting wetter – and in some cases, downright disappearing – as we pave over paradise. We can’t afford to ignore “nature’s sponge” a moment longer.

by Mark Douglas Wessel, photography by Doug Burlock

We have a global water crisis and it’s getting worse. That’s the stark message of a United Nations news release distributed earlier this year, which proclaimed that “three-quarters of all natural disasters in the last 20 years were water related, including floods, landslides and other extreme weather events.”

The announcement goes on to observe that the knock-on effect of these events has included “water pollution, water scarcity, water-related disasters and damage to healthy freshwater ecosystems.” This in turn has negatively impacted on “our rights to life, health, water, sanitation, food, a healthy environment and an adequate standard of living.”

One might reasonably conclude that this ominous messaging is linked to such faraway places as Africa, Australia or even Southern California – parts of the world that consistently make headlines tied to serious water challenges.

But the reality is that this water crisis is just as relevant to what’s going on right here … where we eat, sleep, work and play.

Consistent with the real-world ebb and flow of our shoreline, eight years ago the education and scientific group Georgian Bay Forever announced the results of a NASA mapping study, which concluded that between 1987 and 2013, Southern Georgian Bay lost almost 11 per cent of its wetlands due to historic low water levels. Fast-forward to just last year and communities from one side of the Bay to the other were experiencing devastation brought on by historic high levels of water.

High water and violent waves led to the closure of waterfront paths in Owen Sound, threatened the survival of a shoreline pavilion in Meaford and caused major erosion in Collingwood’s Sunset Park. And as one television station described it, Wasaga Beach was “swallowed” by rising water levels.

In recent years our water quality has been threatened as well. A classic example is Stewart Lake in the Township of Georgian Bay, where just last year the Simcoe District Health Unit advised locals against swimming, fishing or using the water for drinking.

No one would blame you if you concluded that these storylines sound more like something out of a science fiction novel versus real-world news. Because after all, we do live in a land of plenty, don’t we?

Canada is one of only two countries in the world (Russia being the other) bordered by three oceans. And from sea to sea to sea, our landscape is dotted with over two million lakes and rivers, equivalent to 20 per cent of the world’s freshwater supply. The Great Lakes alone, which of course includes Georgian Bay at our doorstep, is the largest group of freshwater lakes in the world, accounting for 18 per cent of the global stock of fresh surface water.

When you contrast those numbers with other parts of the globe where water has become so scarce that some experts predict it could eclipse the value of gold, then on the surface, things are swimmingly good.

But back to reality, that’s when you can swim. Because every year local health authorities collect water samples from public beaches to test for levels of E. coli bacteria, which when deemed too high, can result in beach closures. And last year alone, a host of local beaches were closed due to unacceptably high levels of bacteria, including Sunset Point in Collingwood, Washago Centennial Park Beach in Severn and Mackenzie Park Beach in Tay.

The reason why high levels of E. coli are occurring in the first place can be attributed to multiple sources. As explained on the Simcoe Muskoka District Health Unit website, “bacteria levels can increase in recreational beach water due to heavy rainfall, cloudy water, a large number of swimmers, a large number of birds, shallow water, wet sand, wind and high waves. Beach water may also be unsafe due to excessive weed growth, oil, floating debris, turbidity and blue green algae blooms.”

To appreciate why this is happening, one needs to take a closer look at the source of the problem, which is essentially the source of our freshwater supply: our watersheds.

For many years now, our watersheds – the land areas from which freshwater flows to a stream, river or lake – have been subject to a growing number of external threats, from global warming to pollution to urban sprawl and mismanaged intensification. These threats in turn have given rise to a whole host of challenges that have negatively impacted our way of life, ranging from such short-term inconveniences as beach closures, to alarming shoreline erosion; threats that are just as relevant here in Southern Georgian Bay as they are in other parts of the country.

Watersheds

What are they, anyway?

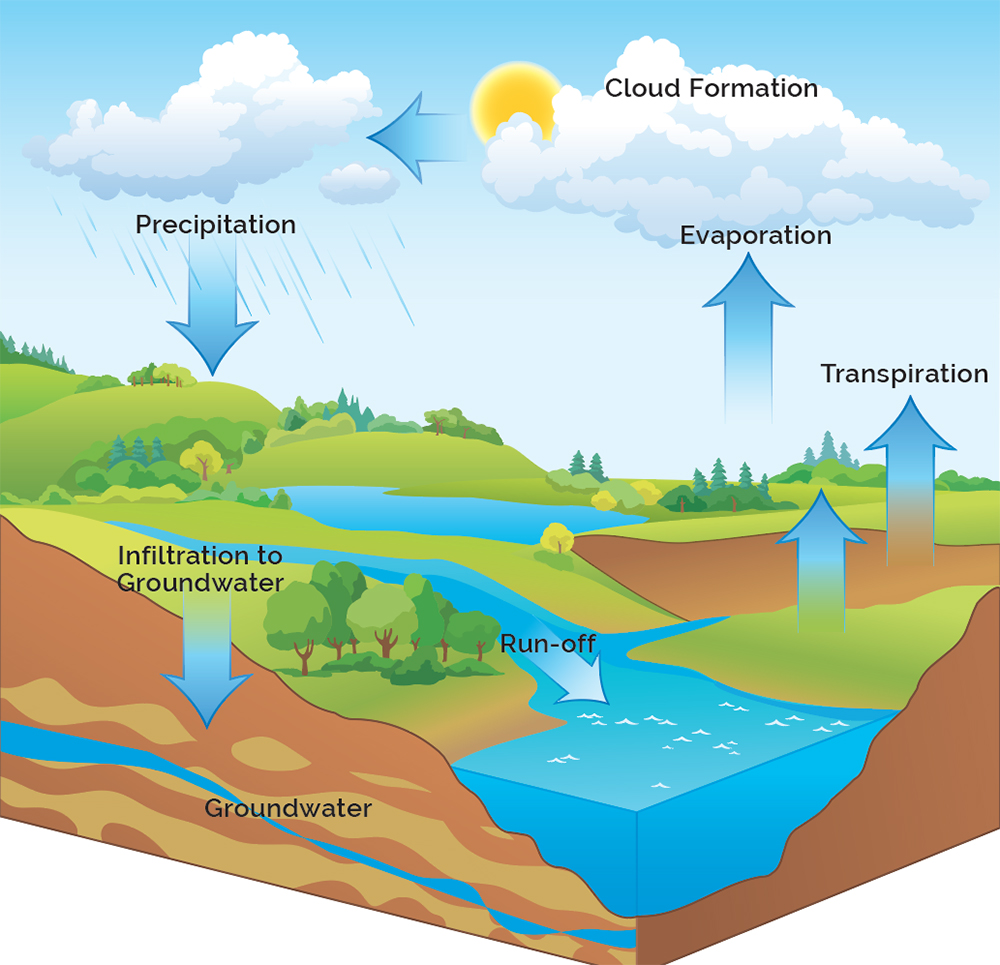

A watershed is a land area that channels rainfall and snowmelt to marshes, creeks, streams, rivers and groundwater, and eventually to outflow points such as bays, lakes and the ocean. Homes, farms, cottages, forests, small towns, big cities and more can make up watersheds. Some cross municipal, provincial and even international borders. Watersheds come in all shapes and sizes and can vary from millions of acres, like the land that drains into the Great Lakes, to a few acres that drain into a pond.

When rain falls on dry ground, it can soak into, or infiltrate, the ground. This groundwater remains in the soil, where it will eventually seep into the nearest stream. Some water infiltrates much deeper, into underground reservoirs called aquifers. In other areas, where the soil contains a lot of hard clay, very little water may infiltrate. Instead, it quickly runs off to lower ground.

As water runs over and through the watershed, it picks up and carries contaminants and soil. If untreated, these pollutants wash directly into waterways carried by runoff from rain and snowmelt. These contaminants can infiltrate groundwater and concentrate in streams and rivers, ultimately being carried down the watershed and into the ocean.

During periods of heavy rain and snowfall, water may run onto and off of impervious surfaces such as parking lots, roads, buildings and other structures because it has nowhere else to go. These surfaces act as “fast lanes” that transport the water directly into storm drains. The excess water volume can quickly overwhelm streams and rivers, causing them to overflow and possibly result in floods. Flooding can also overwhelm sewer systems, causing them to overflow into nearby streams and rivers.

Lake Huron, which includes Georgian Bay, has the largest watershed area of all the Great Lakes.

How do we mitigate such challenges as pollution and flooding in the first place? And are there better ways to promote the economic growth and vitality short of turning the entire region into a nature preserve?

Our New Normal?

If you ask David Sweetnam, a biochemist and executive director of Georgian Bay Forever, to describe the current state of our watersheds, his unhesitating response is: “Everything is in a state of flux. There are a lot of changes going on (in terms of) impacts of invasive species, climate change, warmer water, warmer temperatures, less ice cover and the literal collapse of the food web out in the pelagic zone … the offshore zones of Georgian Bay.” He adds that as a consequence of all of this havoc, “one of the things we’re trying to figure out is what our ‘new normal’ is going to look like” moving forward.

This new normal will, of course, be influenced by global warming. As NASA’s website explains, rising temperatures intensify the earth’s water cycle, increasing evaporation, which results in more frequent and intense storms and greater risk of flooding. Conversely, warming can also contribute to much less precipitation away from storm tracks, leading to increased risk of drought.

In other words, it’s a pendulum swing of extreme weather conditions with which residents of Southern Georgian Bay are all too familiar. In sharp contrast to all-time low water levels until 2013, within the span of less than a decade, we’re now experiencing record high water marks.

Sweetnam notes that water levels have always ebbed and flowed over the years by as much as 1.9 metres. More alarming is the fact that “from that historic 2013 low, we got to an all-time high in just seven years … whereas before that (the swing) might have taken a couple of decades.”

One contributor to higher water levels are the increasingly severe storms we are witnessing. “New climate models are coming out which are showing a 35 per cent increase in storm sizes,” observes Sweetnam, adding that specific to Georgian Bay, “over the last three years, an all-time record amount of water has flooded into the watershed. That’s on top of a water table that was largely saturated through 2017, 18 and 19. So if you look at NASA’s gravimetric data (from space satellites) you can see the amount of ground water in the watershed was almost full and all of that rain couldn’t soak into the wetlands, so it ran into the Bay.”

As a consequence, Sweetnam says the wastewater treatment plans of towns like Midland have been inundated in recent years by huge amounts of water, resulting in “three different discharges of over a million litres” of sewage into the bay. And in Collingwood, new development has ground to a halt after the town recently announced that the water treatment plant is at 80 per cent of capacity or higher and must be expanded to keep up with demand. However, an expansion would not be completed until late 2025.

Eating Away at the Bay

Arguably the most visible, disturbing consequences of having to cope with such increased volumes of water has been the erosion that has occurred on our shorelines and riverbanks. “Residents of Southern Georgian Bay are well aware of shoreline damage,” says Mary Muter, chair of the Georgian Bay Great Lakes Foundation. “The Town of Wasaga Beach was essentially shut down last year with higher water levels and rocks washing right up to the paved road that runs along the beach.” She adds that flooding in recent years has also overwhelmed the dock areas of Penetanguishene, Midland and Parry Sound, representing a serious hit to communities where summer traffic is the lifeblood of their economies.

Despite the essential role they play in flood and pollution mitigation, according to Ducks Unlimited Canada, over 70 per cent of the country’s wetlands in settled areas have either been destroyed or degraded.

Further to the west, Tim Granthier, chief administrative officer of the Grey Sauble Conservation Authority, says that area is facing “very intense pockets of rainfall” that have been particularly hard on smaller streams, which often have less vegetation. “So you get a flash system where heavy rain hits, and a lot of water goes through [within a short period of time], causing a lot of erosion and possibly causing flooding.” And then as quickly as the rain has come, it’s gone. “So it’s bad for the stream system. And it’s bad for the people that live on the stream system.”

Some Hard Truths

Exacerbating our new normal of increased precipitation and wild weather swings is the fact that in urban settings, we’re rapidly paving over the world we live in. Already more than half the world’s population lives in urban settings and the UN projects that figure will grow to 68 per cent by 2050. And going hand in hand with urban development is the fact that anywhere from 50 to 94 per cent of cities and towns are composed of hard, impermeable surfaces.

Rooftops, driveways, roads and parking lots, by virtue of their lack of porosity, quickly shunt water away, adding to flooding concerns during heavy rainfall. In urban settings, that flooding can carry with it everything from oil and gas spills to fertilizers and pesticides, flowing away from our driveways and lawns into our sewer drains and then out into Georgian Bay.

Since 2001, communities north of the GTA – such as Simcoe and Muskoka – have grown by 26 per cent, outpacing Ontario’s overall growth rate of 18 per cent. In other words, this area’s population is increasing at a pace more than 40 per cent faster than the rest of the province. And that rate of growth is expected to accelerate, with communities like Collingwood projected to almost triple in size from its current population of 22,000 to 60,000 residents over the next 40 years.

Arguably one of the most telling indicators of this growth is that Collingwood’s council just passed an interim control bylaw suspending the issuing of new residential permits for at least a year. This due to the fact the town’s water treatment plant (which also serves the town of The Blue Mountains and New Tecumseth) can’t keep up with the local demand for potable water.

This type of growth shouldn’t come as a surprise, mind you. As those of us living in Southern Georgian Bay know full well, between the Niagara Escarpment and the Bay itself, the area is blessed with natural beauty. So why would someone from the 416 or 905 area codes not want to move here – especially since COVID hit, which on the one hand has accelerated the acceptance of working from home or telecommuting and on the other, has heightened our appreciation for access to parks and public space.

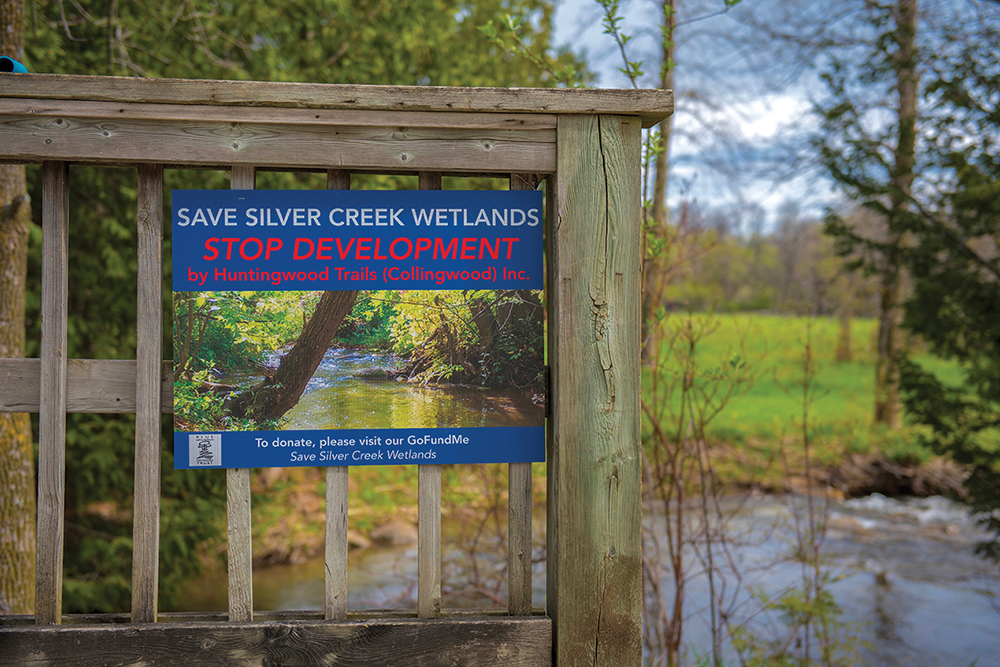

But in spite of this demand, some residents would like to see local leaders take a more balanced approach to growth, recognizing the serious impact urban sprawl can have on environmentally sensitive areas. As Paul Neate, resident and spokesperson for the Save Silver Creek Wetlands community group, sees it, “the development that’s coming out west of Collingwood is very much like Brampton,” in contrast to which he says his group “wants to maintain some of the natural beauty that has existed [here] and which is why people have come here in the past … without being so naive as to think that it’s always going to be woodlands and bears and deer. But we need to preserve some of it. We don’t have to develop every single inch of property.”

Neate’s group – with support from other local organizations such as the Blue Mountain Watershed Trust, have been embroiled in a David and Goliath struggle to stop development projects on land surrounded by the Silver Creek Wetland. One site – known as Bridgewater on Georgian Bay, has been around since the early 2000s. Initially, 328 units were proposed and in 2016 the application was modified to increase the density of the development to more than 600 homes. Another project, Huntington Trails, initially sought to build 437 homes on a 121-acre parcel, which was denied by the Local Planning Appeal Tribunal (formerly the Ontario Municipal Board). The builder now has draft plan approval for up to 179 residential units.

[Editor’s Note: Development adjacent to the Silver Creek Wetland is an evolving issue, with possibly two closed meetings held between researching this article and the time of its printing. We are aware of a change to the boundary and focus of the proposed development area. Huntington Trails was to submit a revised development plan on June 14, 2021.]

“From our perspective, there’s a lot of development going on in the area already, so why do we have to build on this very sensitive land,” questions Neate, concerned that the development threatens to cut off Georgian Bay from the watersheds that extend all the way from Blue Mountain.

Wetlands

5 reasons to love them

Wetlands are areas where water either covers the soil or is present at or near the surface of the soil.

Wetlands are often thought of as wastelands of stagnant, stinky water on the sides of highways and farmers’ fields. While wetlands are often pungent with decomposing organic matter, they are far from being wastelands.

In fact, wetlands are one of Earth’s more productive ecosystems, supporting an incredible amount of biodiversity, and considered a nature-based solution to climate change. In spite of their crucial role, we’ve lost over a third of our wetlands globally over the past 45 years. Here in Canada, wetlands including marshes, swamps, fens and bogs make up 14 per cent of our landmass. Here are five reasons to love our wetlands:

1. They’re home to a diversity of species

In the spring, wetlands are brimming with waterfowl and shorebirds as they nest and raise their young in the safety of reeds, grasses and stones. Wetlands are also home to a wide variety of fish species, frogs, turtles, muskrats, minks and beavers that are long-term residents. With deer mice and ground squirrels living in the grasses adjacent to wetlands and fish swimming in open water, this ecosystem is a favourite of osprey, eagles and hawks. Aquatic invertebrates such as dragonfly nymphs, tadpoles and snails form the base of the wetland food chain.

2. They’re the kidneys of the planet

Wetlands have the wonderful ability to remove pollutants from water, thanks to their luscious vegetation. Cattails, for example, aren’t just good for entertainment with seedy fluff that explodes in the wind. These iconic wetland plants are able to capture excess phosphorous and nitrogen, thereby preventing harmful algal blooms. Even more amazingly, wetlands are able to get rid of 90 per cent of water-borne pathogens. This is crucial as wetlands recharge groundwater, which 26 per cent of Canadians rely on for drinking water.

3. They regulate the climate

Wetlands are masters at carbon sequestration – in layman’s terms, they suck in carbon and store it in the underlying soil. This ability to hog carbons helps to regulate the climate. Some wetlands (known as peatlands or peat bogs) collect partially decomposed plants and other organic matter (a.k.a. a wack tonne of carbon). When peatlands are drained for agriculture, forestry or peat harvesting, carbon and nitrogen are released as greenhouse gases in the form of carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide. Approximately 25 per cent of the world’s peatlands are in Canada alone.

4. They act like giant sponges

Another wetland superpower is their ability to act like a giant sponge. When the clouds open up and rain pours down, wetlands are able to absorb excess water, acting as a buffer against flooding. Now imagine the reverse situation. If it’s dry and the land is parched, wetlands are able to release water back into the environment. In addition to their spongy talents, wetlands act as a protective barrier from storm surges along coastlines.

5. They’re fun!

Protecting our wetlands means we get to enjoy all they have to offer! In the summer, they provide endless entertainment for recreational birders, photographers, canoists, kayakers and hikers with their diverse vegetation and parades of waterfowl, shore birds and wildlife. Wetlands are also perfect for family activities like pond-dipping to explore and learn about all the little creatures living in the marsh. In the winter, the frozen waters of wetlands can provide a surface for skating, while the snow-covered grasses surrounding wetlands provide the perfect opportunity to snowshoe and cross-country ski.

For many years now, our watersheds – the land areas from which freshwater flows to a stream, river or lake – have been subject to a growing number of external threats, from global warming to pollution to urban sprawl and mismanaged intensification.

George Powell, vice chair of the Blue Mountain Watershed Trust, adds one of the most obvious dangers of development taking place in and around wetlands is the threat to natural heritage areas and the flora and fauna indigenous to those areas. “There are species at risk here, from eagles to turtles that are hanging on for dear life. And some of the amphibians, such as salamanders, are actually born inside what we call vertical wetlands that disappear during the summer. So they have to find their way out of the wetland, up into the forest where they actually lay their eggs.”

Groups like Powell’s and Neate’s really are the Davids in the face of immense development pressures, since the province is actively promoting urban growth in this region (as part of its “A Place to Grow” plan), coupled with the reality that local towns desperately need to grow their tax base. But at the very least, says Powell, towns like Collingwood and The Blue Mountains should honour standing commitments to enforce a minimum buffer around wetlands. “A 30-metre buffer is in their official plans, but we rarely if ever get that. In fact, there are certain cases where a developer has had the buffer reduced to 3.5 metres, which is absolutely ridiculous.”

Nature’s Filter & Sponge

Apart from preserving nature, wetlands are an essential part of any watershed in that they naturally filter out upstream pollutants before they hit downstream waterways. And yet, despite the essential role they play in flood and pollution mitigation, according to Ducks Unlimited Canada, over 70 per cent of the country’s wetlands in settled areas have either been destroyed or degraded. And not surprisingly in highly urbanized Ontario, the numbers are even worse. Much of this loss stems from converting wetlands to urban or agricultural areas going back to the times of our forefathers.

“We’ve lost about 80 per cent of wetland across Southern Ontario and in some places like Chatham Kent, it’s more like 98 per cent. So we’ve lost a tremendous number of our wetlands,” observes Wasaga Beach-based Owen Steele, who heads up Ducks Unlimited Canada’s conservation efforts here in Ontario.

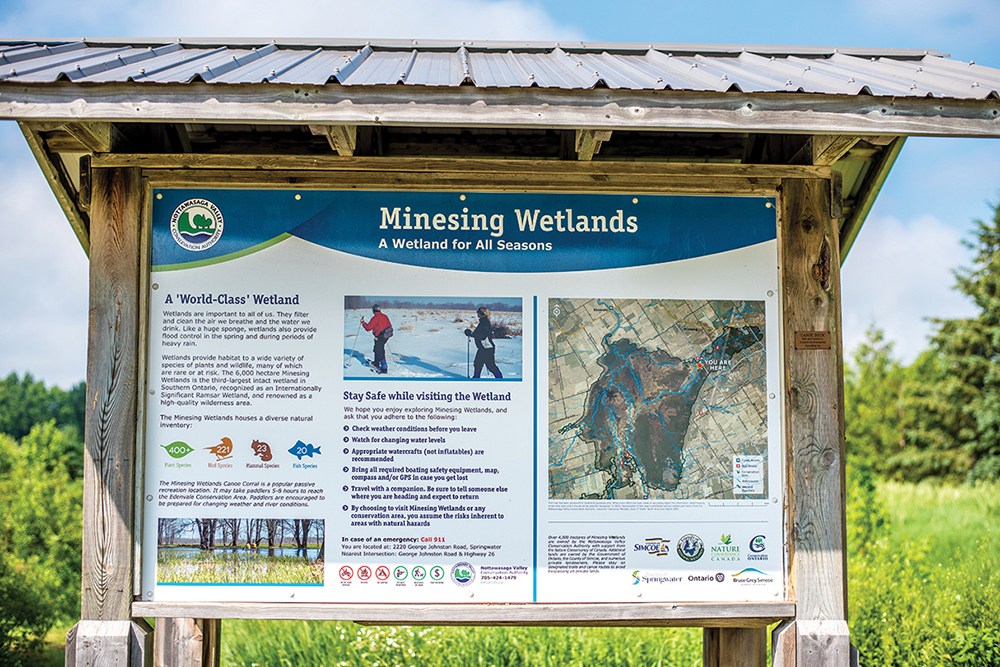

Thankfully in our region, we’ve managed thus far to preserve many of our wetlands. A shining example is the Minesing Wetlands, which provides a much-needed safeguard for Georgian Bay. “It’s a huge reservoir that acts like a big sponge and really helps to hold and reduce flooding in the springtime,” notes Steele. “It takes all that water coming off the agricultural land to our south and absorbs it,” and in the process “it will take a bunch of nutrients and pollutants out of the water and help improve water quality before it hits the bay.”

The idea of nutrients flowing into the bay may not sound like a bad thing, especially along parts of the Georgian Bay shoreline where the water is crystal clear. This is because the water is oligotrophic – lacking in such essential nutrients as phosphorous or nitrogen, which are needed for plants and algae to grow.

Nutrients become a source of concern, however, when you have concentrations of phosphorous – from fertilizers used by farmers to help grow their crops – leaching into adjacent streams. In an imperfect storm, these nutrients – working alone or in concert with warmer temperatures and septic or sewage overflow – can cause algae blooms, which can in turn produce such deadly toxins as cyanobacteria, threatening wildlife and humans alike.

With the Nottawasaga Valley area expecting 100,000 new residents by 2031, that could translate into “huge increased runoff and sewage output” – all the more reason to redouble efforts to protect the Minesing and other wetlands in Southern Georgian Bay.

Focusing on the critical need for wetlands as part of their conservation efforts, Ducks Unlimited has a stewardship program in place to work with rural landowners, from commercial operations to hobby farms, says Steele. Stewardship activities include everything from tree and grass planting to help keep the water in place, to wetland restoration. Some farms, he notes, “are marginal and aren’t really economical to continue to farm. With those, we work cooperatively with the agricultural community to see if we can convert them back into wetlands.”

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) is involved in these reclamation efforts as well. Brittany Hope, who is the conservation coordinator for Georgian Bay and Huronia, says that historically, 100-acre properties were given away to prospective farmers in and around the Minesing Wetlands. “They were basically advertised as a place to come farm, but because the land flooded badly in the spring, they were not great places to farm. So now much of it is abandoned farmland, and [left untended] a lot of invasive species have grown in.”

Whether abandoned farmlands or current, marginal farming operations, the NCC, in partnership with such supporting groups as the Nottawasaga Valley Conservation Authority, has been actively acquiring or accepting land donations to the point that as of now, more than half of Minesing Wetland’s 11,000 acres are protected from further development.

Despite this success, Hope remains wary of the twin threats of unchecked development and climate change. “What I have observed in my time here, which has been well-documented, is that the wetlands are getting wetter. And that’s due to development and impermeable surfaces upstream. So, generally the water flow is pretty fast off of those surfaces, whereas on a natural surface, it tends to slowly infiltrate into the ground.” With the Nottawasaga Valley area expecting 100,000 new residents by 2031, that could translate into “huge increased runoff and sewage output” – all the more reason to redouble efforts to protect the Minesing and other wetlands in Southern Georgian Bay.

To get a clearer understanding of the absorption qualities of wetlands, Ducks Unlimited is now in the second year of a research project in Southwestern Ontario, where the high concentration of agricultural lands in close proximity to Lake Erie has resulted in increasing algae blooms over the years. “We’re looking at the nutrient capture of restored wetland,” explains Steele. “How much nutrient is flowing into the wetlands off the farm fields and how much nutrient is flowing out of the wetlands downstream into Lake Erie.”

The Nature Conservancy’s Hope says a big reason wetlands capture so many nutrients is they slow down the flow of water from incoming streams, allowing sediment in the water to settle and be absorbed by the soil. “Without wetlands, that water would just completely go down the river and potentially cause flooding. In fact, studies have shown the wetlands cut peak flows during storm events in half.”

She says the Minesing Wetlands have a storm capacity of 66 million cubic metres of water. Putting that into perspective, “It’s like 26,000 Olympic swimming pools. Or, if you try and visualize it on the ground, it would cover about 58 square kilometers with one metre of water – the entire size of the town limits of Wasaga Beach.”

Benefits of a Healthy Watershed

Healthy watersheds improve water quality, regulate water flow for drought and flood management, provide wildlife habitat, store carbon, contribute to climate change adaptation, and offer opportunities for recreational fishing and hunting.

Human Health

A healthy watershed ensures safe drinking water, food, enables us to adapt to the impacts of climate change more easily by cooling the air and absorbing greenhouse gas emissions, and provides natural areas for people to enjoy and maintain a healthy and active lifestyle.

Ecological Health

A healthy watershed conserves water; promotes streamflow; supports sustainable streams, rivers, lakes, and groundwater sources; enables healthy soil for crops and livestock; and provides habitat for wildlife and plants.

Economic Health

A healthy watershed produces energy and supplies water for agriculture, industry and households. Forests and wetlands help to prevent or reduce costly climate change and flooding impacts, manage drought, and contribute to tourism, fisheries, forestry, agriculture and other industries.

The guiding principle of Low Impact Development is to help maintain and restore a natural water balance in an urban setting by keeping water onsite through the use of such measures as green roofs; cisterns for collection of water runoff, permeable pavement; and the greater use of bioretention areas that include rain gardens, bioswales (vegetated channels designed to absorb water), and more extensive planting of trees and other vegetation.

Graphic showing the hydrologic cycle of watersheds, which filter precipitation through to groundwater and eventually out to larger bodies of water such as lakes and oceans.

Going from Grey to Green

Despite the overwhelming body of evidence that wetlands are an essential asset for our watersheds, the question that is now top of mind with everyone from politicians to urban professionals to concerned citizens, is not just how do we create more resilient communities in the face of impending disasters, but how do we mitigate such challenges as pollution and flooding in the first place? And are there better ways to promote the economic growth and vitality short of turning the entire region into a nature preserve?

In terms of mitigating urban water runoff associated with new residential development, Mark Palmer, executive director of Collingwood-based Greenland International Consulting Engineers, says there’s an opportunity to significantly reduce residential runoff by implementing Low Impact Development (LID) practices more widely. The guiding principle of LID is to help maintain and restore a natural water balance in an urban setting by keeping water onsite through the use of such measures as green roofs; cisterns for collection of water runoff, permeable pavement; and the greater use of bioretention areas that include rain gardens, bioswales (vegetated channels designed to absorb water), and more extensive planting of trees and other vegetation.

“From a conservation perspective, developers – at least the ones I work with – want to do the right thing [for the environment],” says Palmer. “They want to contribute. But they just also want to be able to buy a piece of land, go to the bank, get their financing and be able to build homes. So if we want them to cooperate and be involved in such things as LID, we need to update the design standards … but also work out timelines that are amicable to helping our economy.”

The need to stop doing the same thing and expecting different results shouldn’t fall solely on the shoulders of builders or new residential developments, either. Change needs to occur in existing neighbourhoods and public areas as well. Cognizant of this duty, municipalities from coast to coast are beginning to play an active role in embracing what has become known as the “sponge city” mindset.

For instance, the City of Vancouver has developed a comprehensive Rain Strategy document tied to promoting green rainwater infrastructure on both public and private land. Some cities like Mississauga are using a ‘stick’ approach by introducing stormwater charges, based on the hard surface area homeowners have on their properties. Others, like Kitchener – which also levies a fee tied to impermeable surfaces – have tried using a rebate program that provides a credit for homeowners who take on such tasks as installing a rain barrel or replacing their old asphalt driveways with permeable pavement.

And these communities are learning as they go along. For instance, Kitchener came to the conclusion that the credit program didn’t provide a strong enough incentive for homeowners to act. So they’re now looking at following in the footsteps of cities like Ottawa, which just launched a residential stormwater management program that targets more flood-prone neighbourhoods. Ottawa’s program provides homeowners with a credit of up to $5,000 to cover the added cost of doing everything from creating rain gardens to installing permeable driveways.

Palmer describes this sort of rainwater harvesting as “low-hanging fruit,” which is why his firm pioneered a bioroof system on their main office building a few years ago. The system not only collects water but also helps to reduce the “heat island” effect by absorbing solar energy and gradually releasing water, which in turn helps cool the air.

Change needs to occur in existing neighbourhoods and public areas as well. Cognizant of this duty, municipalities from coast to coast are beginning to play an active role in embracing what has become known as the “sponge city” mindset.

How You Can Help

10 things you can do today

1. REDUCE ROOFTOP RUNOFF: Excess runoff can cause flooding and stream bank erosion during rainstorms. Minimize runoff by redirecting downspouts into vegetated areas, installing rain barrels or planting a rain garden. Use the stored water for your garden and other landscaping.

2. MINIMIZE FERTILIZER: Nutrients from fertilizer runoff can lead to excess plant and algae growth in waterways. Have your soil tested to determine fertilizer needs and only apply the recommended amount of each nutrient.

3. MAINTAIN YOUR SEPTIC SYSTEM: Septic system failures can be costly and can contaminate groundwater and nearby surface waters. Have your septic system inspected and pumped every three years.

4. SCOOP THE POOP: Pet waste left out in the yard, on sidewalks or on roadsides washes away when it rains and is a major contributor to bacteria problems in local waterways. Dispose of pet waste properly by flushing it down the toilet, burying it in your yard or putting it in a sealed bag in the trash.

5. PROPERLY DISPOSE OF HOUSEHOLD HAZARDOUS WASTE: Never pour chemicals, pharmaceuticals, oil or paint into the storm drain. Check with your county’s household hazardous waste program to properly dispose of or recycle chemicals and keep them out of your waterways.

6. GO NATIVE: Reduce your lawn by adding native trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants to your landscape. They require less water and fertilizer and are more resistant to pests and disease since they are already adapted to local conditions.

7. PLANT A STREAM BUFFER: If you have a stream on your property, provide a natural buffer of native trees and shrubs along its banks to help filter polluted runoff, control erosion, and provide essential fish and wildlife habitat.

8. USE COMMERCIAL CAR WASHES: The best place to wash your car is at a commercial car wash, many of which filter their water before directing it to treatment plants. If you wash your vehicle at home, park it on the grass first, so your lawn absorbs some of the detergent runoff and contaminants.

9. BE WATER WISE: Conserve water by using low-flow faucets, showers and toilets, repairing leaks, taking shorter showers, and turning off the tap when brushing your teeth. Run dishwashers and clothes washers only when full, and wash your car and water your lawn only when necessary. You will not only be conserving water but also saving money!

10. GET INVOLVED: We all live in a watershed, and every drop counts. Do your part by joining your local watershed organization, participating in community clean-ups, and supporting environmental legislation.

Engaging from the Ground Up

From a much bigger-picture perspective, Palmer is also involved in discussions amongst mayors around the Great Lakes in Canada and the U.S. who are concerned about shoreline water levels and are actively seeking solutions to this daunting challenge. Palmer is just one of many professionals on the front lines of mitigating climate change advocating for the public to play a greater role in both finding and implementing solutions that can positively impact the community.

Palmer is convinced that communities everywhere need to actively manage shoreline lands so they’re more adaptive to environmental change. And he sees public engagement as an essential part of this process. “You’ve got to get them to be part of the solution and not have developers drive [the process].”

Dave Featherstone, a senior ecologist with the Nottawasaga Valley Conservation Authority (NVCA), says we can all do our bit on the home front through such measures as putting in rain barrels and growing natural gardens that promote biodiversity. “It seems like such a small thing to do, but the cumulative impact is pretty impressive.”

Equally important, he says, is for residents to have their voices heard in public forums instead of passively watching major plans unfold that will impact on the environment. “For instance, with initiatives such as natural heritage mapping (in which NVCA is actively involved), if people are concerned about our natural heritage or types of development, then it’s a great opportunity for the public to become involved and make their views known. It’s really where the rubber hits the road.”

Getting the public to play a more active role in local decision making isn’t likely to be an overnight process. As with any transformative change, it could very well be a multigenerational or youth-up process. Which perhaps helps to explain that in contrast to boomers, millennials are more focused on driving the world away from eating meat than driving cars.

Responding to this citizen engagement challenge, groups such as the Grey Sauble Conservation Authority plan to ramp up their educational programs. “We really want to start moving forward with educational tools to educate people about what a watershed is,” says Granthier. “Right now, if you were to ask ‘what do you think people get about the watershed concept,’ I think the reality is that most people don’t get it. If you take the time to educate people about watersheds, they will understand. But right now, when we talk about watersheds, most people don’t know what that means.”

As part of spreading the word, Georgian Bay Forever’s Sweetnam says it’s all about “connecting people with their shoreline and connecting people with the water,” in contrast to the current disconnect some of us seem to have. As if to underscore this argument, Sweetnam recalls something he recently witnessed: “I saw somebody smoking a cigarette, and then they stepped over the storm sewer and they threw it down the storm sewer thinking out of sight, out of mind, right? That it won’t be on the street at least.”

Unbeknownst to that person, however, “that storm sewer doesn’t have any filter on it. So whatever goes (into the storm sewer) flows right out into Georgian Bay.”

Clearly we have work to do, and it starts with educating residents of all ages (from pre-schoolers to senior citizens) as well as local governments, businesses and developers about the importance of watersheds and the numerous benefits they provide, from scrubbing our water clean to flood control and promoting biodiversity. Through education, increased awareness and action, we can all do our part to protect these natural wonders, ensuring an ample supply of clean, fresh water to drink and enjoy for centuries to come. ❧

Find Out More

To learn more about wetlands, watersheds and how you can help, visit these websites:

Blue Mountain Watershed Trust

watershedtrust.ca

Ducks Unlimited Canada

ducks.ca

Georgian Bay Forever

georgianbayforever.org

Georgian Bay Great Lakes Foundation

georgianbaygreatlakesfoundation.com

Grey Sauble Conservation Authority

greysauble.on.ca

Nature Conservancy of Canada

natureconservancy.ca

Nottawasaga Valley Conservation Authority

nvca.on.ca