Fifty years ago, Canadian scientists first discovered the monarch butterfly’s overwintering site in the mountains of Mexico—but that’s just one piece of the enduring mystery of monarch migration.

by Audrey Armstrong // photography by Willy Waterton

It sounded like a soft breeze blowing through leaves. As the sun reached branches of the ancient oyamel fir trees in the Sierra Madre mountain range of central Mexico, warmth penetrated the tiny cold-blooded bodies of the orange and black monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus). The soft rustling of wings increased to a whirling crescendo; suddenly millions of monarchs cascaded into the air in unison.

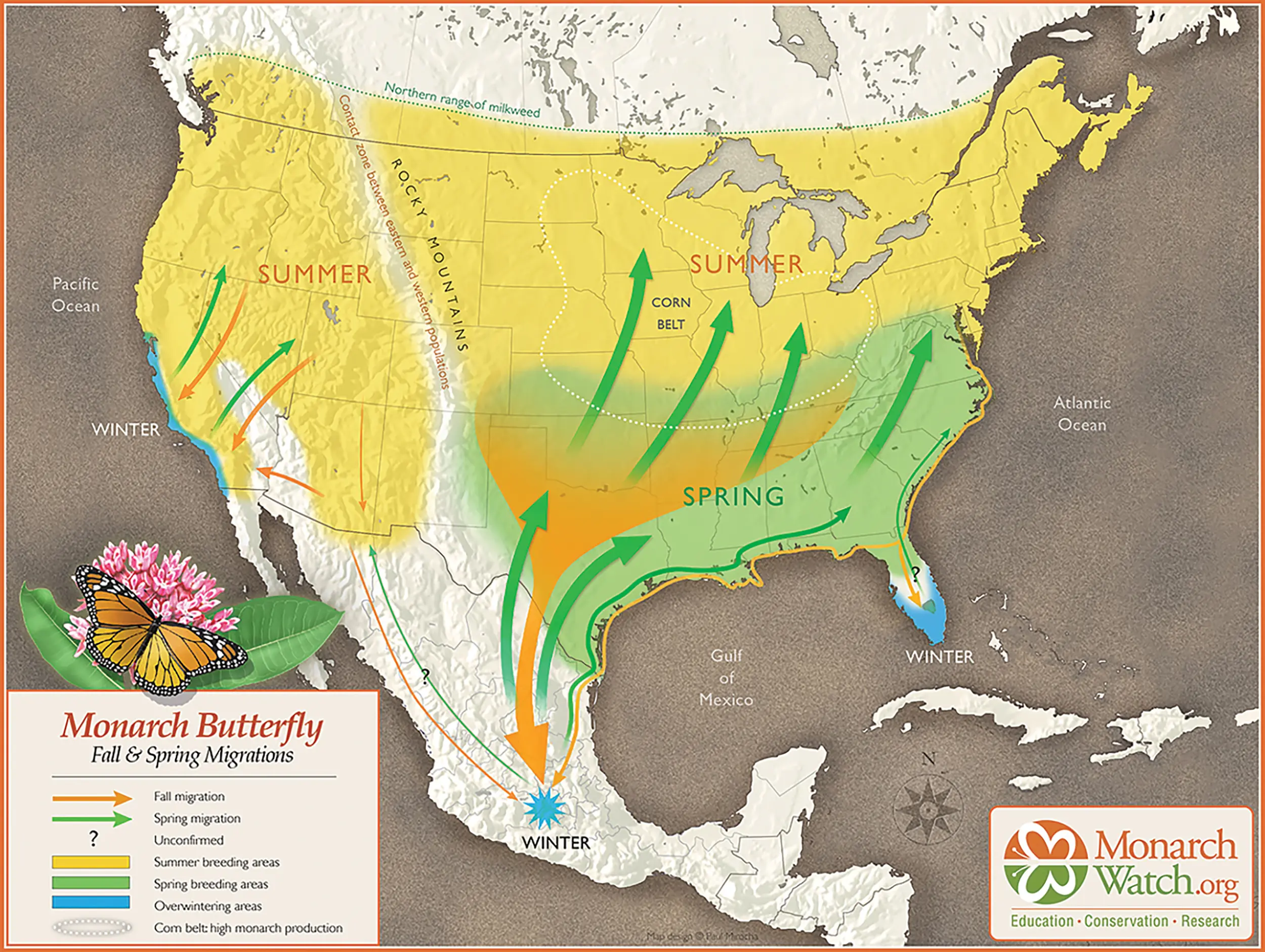

Monarch magic had begun! We stood in awe as the snowstorm of overwintering butterflies exploded overhead. By late February or early March, mated female monarchs leave Mexico, heading north in a remarkable relay race-style migration. Some head towards our backyards in Southern Georgian Bay.

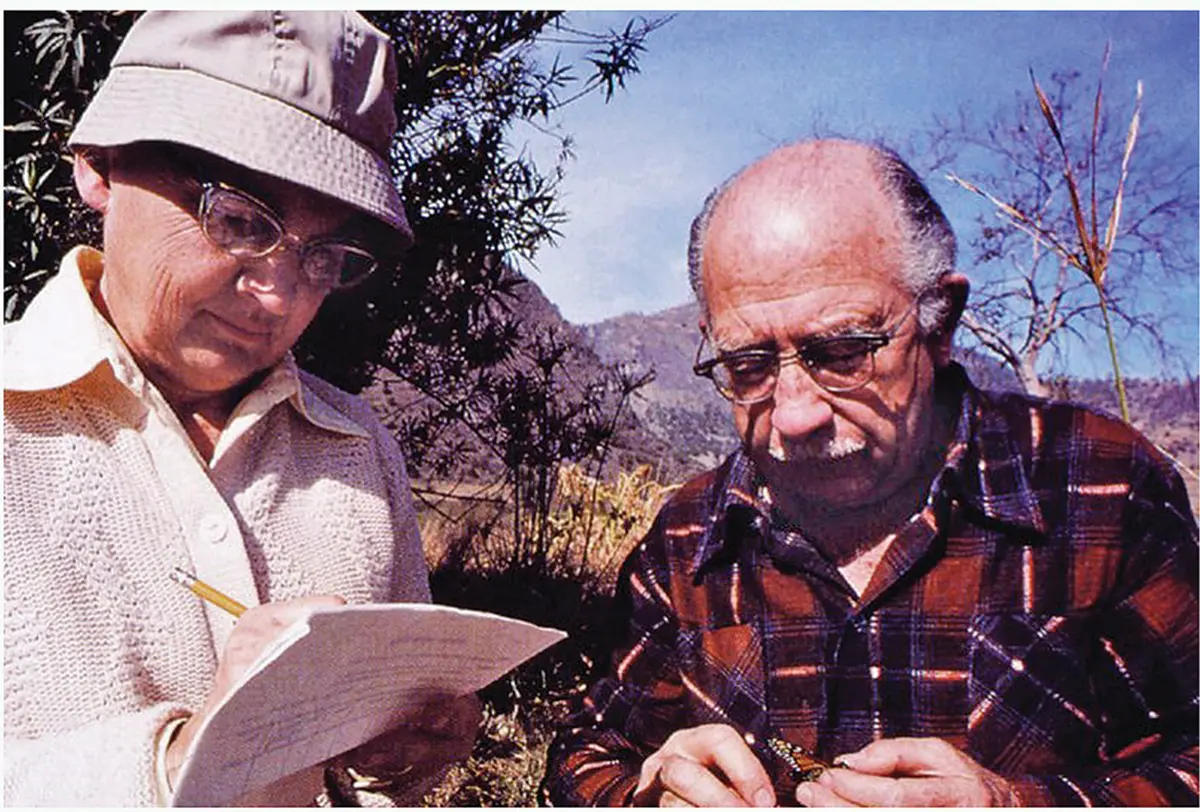

It was mid-February when my husband, photojournalist Willy Waterton, and I travelled to Mexico with the Monarch Teacher Network. We were standing in the same cluster of forested volcanic peaks in central Mexico where, 30 years earlier, Canadian zoologist Fred Urquhart and his wife Norah first witnessed this remarkable natural spectacle of monarchs in the millions. The Urquharts solved one of the world’s great natural mysteries after decades of research beginning in 1937. They involved thousands of citizen scientists, who helped them determine the trajectory of the monarch’s southward migration, when the overwintering forests were found. It was 50 years ago this past January that the Urquharts’ insect research associates, Ken Brugger and Catalina Trail, found the monarch overwintering site at Cerro Pelon with help from Mexican woodcutters. Brugger phoned the Urquharts in Toronto and said, “We have found them, millions of monarchs, in evergreens beside a mountain clearing.”

Although the discovery was massive for the scientific community, it was already known to Indigenous people. Mexicans believe monarch butterflies are the souls of departed family members and the monarch’s arrival usually coincides with Day of the Dead celebrations in Mexico, on November first.

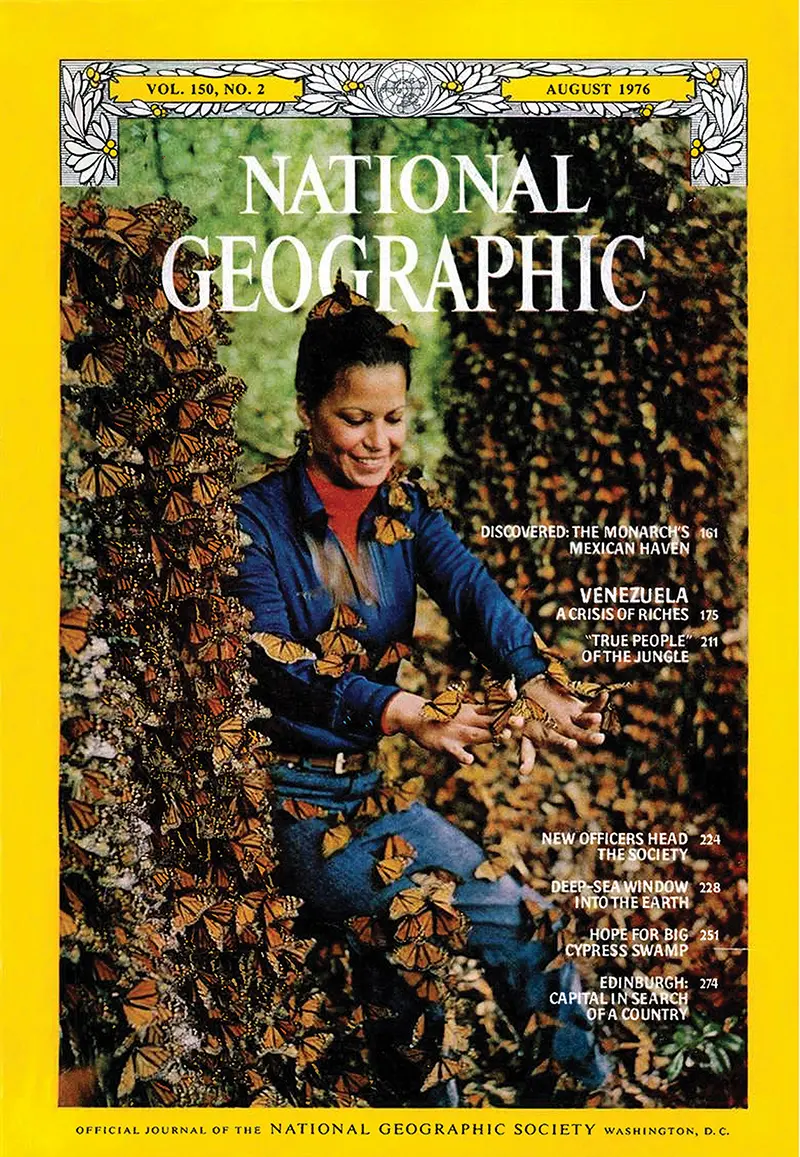

Just a year after the National Geographic article appeared in August 1976 announcing this discovery to the world, Canadian filmmakers Peter and Fran Mellen travelled the same route as the Urquharts to film a poetic movie, Monarchs. They also recorded the butterfly’s astonishing life cycle along the rocky Saugeen River near Durham, Grey County.

Meaford high school teacher Lloyd Beamer was one of the original citizen scientists, tagging monarchs for the Urquharts with his students and reporting back to Fred Urquhart in 1954.

The soft rustling of wings increased to a whirling crescendo; suddenly millions of monarchs cascaded into the air in unison.

“Monarchs were not only scarce during the tagging period, they have been decidedly scarce all summer,” Beamer wrote that year. “During September our students collected only one monarch. I have not seen a single larva or chrysalis this season.” Then, in 1956, he commented, “…on September 1, monarchs were so plentiful along the highway between Barrie and Midhurst (Hwy 26) that they slowed traffic almost to a walk.”

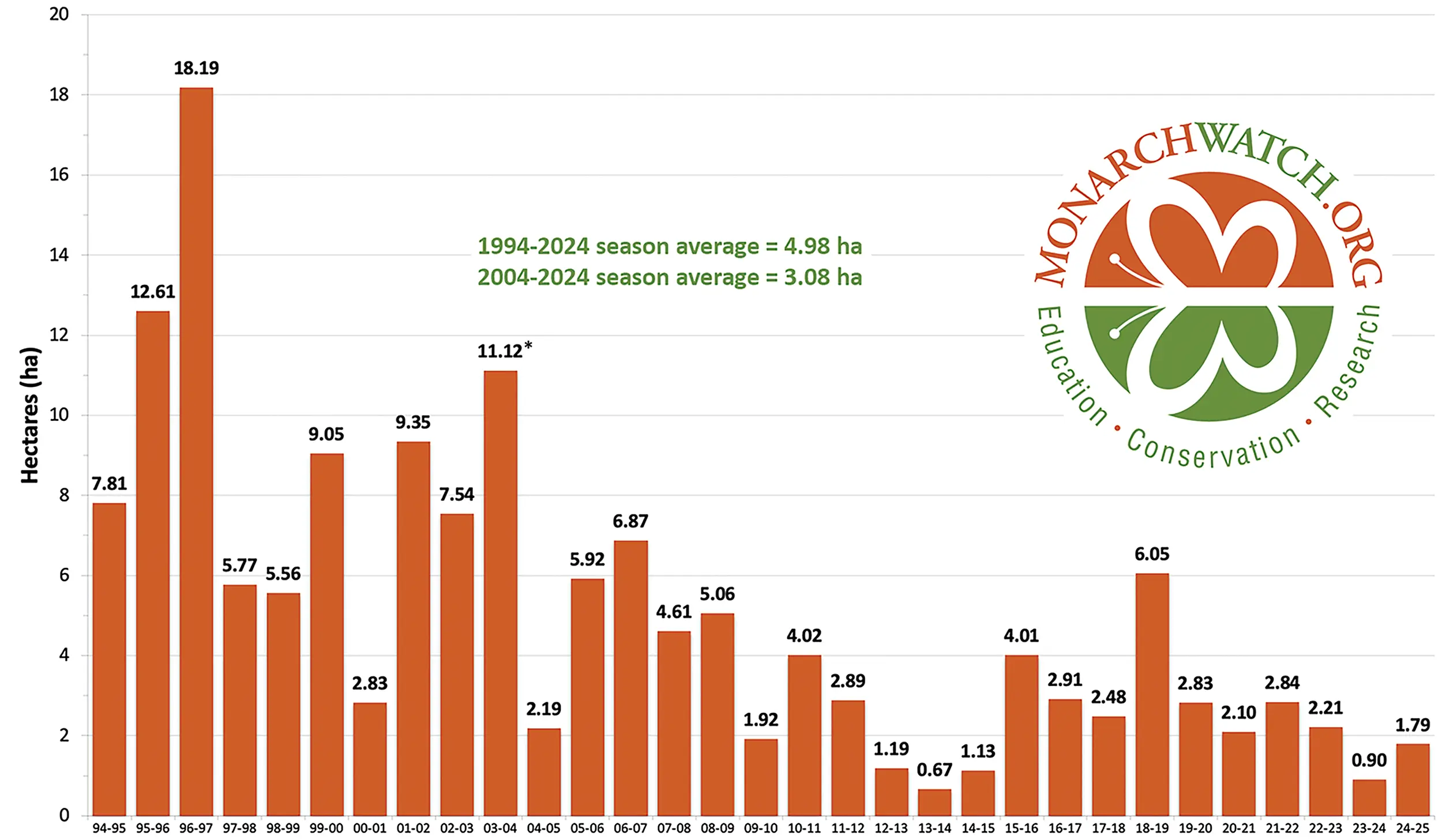

We know monarch numbers have varied over the years. Populations of animals often go through cycles of highs and lows. But the current numbers are alarming. The North American eastern population has declined by 90 percent over the last 20 years and the small western population overwintering in California has declined by an estimated 99.9 percent over 45 years. The government of Canada listed monarchs as an endangered species under the federal Species at Risk Act in December 2023. Found globally, monarchs as a species will not likely go extinct, but the epic North American monarch migration is at risk.

My furthest recovered tag was from a monarch tagged in August 2006 in Tobermory. That tag was found in El Rosario, Mexico, on February 27, 2007, a remarkable distance of 4,121 kilometres.

You might wonder how we tag monarchs. The process is similar to how the Urquharts tagged so many years ago. An adhesive tag slightly larger than this O is gently pressed onto the lower wing of the butterfly. Each tag purchased from Monarch Watch has a unique code and the database identifies the exact geographic origin, date and sex of each monarch, linking it to the citizen scientist who tagged it. Although we know where monarchs overwinter, scientists are still looking for answers to other questions. The recovered tags help scientists learn more about specific migration routes, patterns, timelines, population size variations, locations of stopover sites and the impact of extreme weather events on migration.

After 18 years of tagging hundreds of monarchs, I’ve had four tags recovered in Mexico. All of those were monarchs that children helped me tag, adding to the educational significance of the recovery. My furthest recovered tag was from a monarch tagged in August 2006 in Tobermory. That tag was found in El Rosario, Mexico, on February 27, 2007, a remarkable distance of 4,121 kilometres.

Monarch tagging events are an opportunity to educate participants young and old about threats to monarchs. Use of pesticides, insecticides, spread of pathogens, climate change (extreme weather events) and massive habitat loss, both here and in the overwintering sites, all impact monarch populations. The events also provide an opportunity to explain how we can help monarchs by planting native milkweed in pollinator gardens. Although adult monarchs will nectar on many flowers, the only plant females lay eggs on is milkweed. This becomes a perfect teachable moment to share the magic of monarchs.

About 19 percent of monarchs overwintering in Mexico are from Ontario. They emerged from gold-flecked, lime-green chrysalises here in mid-August, their bodies in reproductive diapause. Nutrients and energy normally required for reproduction are channeled to heavier flight muscles and fats for their long journey south. This fourth generation we call the super generation.

They often return to the exact same sites, even the same branches year after year. Is it ancient memory or pheromones on branches?

It’s thought these tropical butterflies may have followed the receding ice age glaciers north as milkweed (their only host plant) expanded its range in the post-glacial warming climate. As sunlight wanes and temperatures drop in late summer, this super generation of monarchs begin to journey south, arriving at their Mexican overwintering sites having survived storms, pesticides and predation.

It took us just five and a half hours to fly to Mexico from Toronto. However, for the half-gram monarch (the weight of a single chocolate chip), the journey to their winter home in the Sierra Madre takes about two months. They have never been there before and won’t return again. Using the sun for navigation (their antennae contain light-sensitive magnetic sensors) they glide on air currents and thermals, conserving energy. After a flight of 4,000 kilometres—or possibly up to 7,000 as they don’t fly in a straight line—they enter a state of torpor or inactivity, clinging to the oyamel fir trees till mid-February. At that time, their reproductive organs have fully developed and they will mate within a rich gene pool of the entire eastern North American monarch population.

In March, the mated females begin the multi-generational migration north. While most males die within Mexico after mating, the females leave, heading northeast, searching for milkweed in Texas and the Gulf states to lay their eggs on. The super generation female dies there. Their offspring continue the relay race north. The generation we look forward to seeing this spring will be the children or grandchildren of the original super generation monarchs.

The monarchs we see in Southern Georgian Bay beginning mid-May to mid-June live a very short life compared to the fall super generation that live up to nine months. Summer monarchs will live for only six weeks before dying. We host two to three generations of monarchs in Southern Georgian Bay every summer, and with each generation, the population increases exponentially.

Monarch roosting in Mexico is one of the natural wonders of the world. But you can observe the natural phenomenon of monarchs roosting in the hundreds right here in Southern Georgian Bay during fall migration. When strong winds or temperatures below 13 C prevent flight, clusters of monarchs roost in trees, along the shore, on islands or inland. It’s actually more exciting to us than the large colonies in Mexico, because we know this is the super generation that flourished here in Ontario. The Bruce Peninsula along with Georgian Bay shorelines funnel the monarch migration south. We have been fortunate to watch hundreds of monarchs stream ashore near Big Bay on an August evening, and we have also witnessed over 2,000 monarchs roosting on maple trees along the Saugeen River near Port Elgin during several cold, windy September days. They often return to the exact same sites, even the same branches year after year. Is it ancient memory or pheromones on branches? Why do they return to the same locations in Mexico every year? There are still many questions scientists need to answer about monarchs.

As a retired educator, the magic continues for me when I show our granddaughter the tiny yellow, white and black-striped caterpillars eating swamp milkweed leaves in my pollinator garden. As they grow, it’s the classic Eric Carle story, with caterpillars getting larger and larger just like in the The Very Hungry Caterpillar. When adult monarchs fly around in our gardens, nectaring and laying eggs, our granddaughter calls out to them, “Flutterby, flutterby!” as she experiences the magic of monarchs.

How to Help Monarchs

The best way to help monarchs is to create habitat. Milkweed is the monarch’s only host plant and it is the only plant female monarchs will lay eggs on. You can help to grow the monarch population over the critical summer months by planting milkweed. Females will find the plants and lay eggs on them, and you will have an opportunity to witness the monarch’s magical life cycle in your own backyard.

There is more than one kind of milkweed. I suggest planting native swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) and butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa). Both are native to our area. Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) is good to plant in meadows or wide-open areas as it is spread by underground rhizomes.

Some people think raising monarchs would be a good way to increase the population. However, what often happens in captivity is a parasitic protozoan, Ophryocystis elektroscirrha, develops inside the monarch larva and pupa, and is transmitted from generation to generation by spores. For this reason, along with new science that suggests raised monarchs are sometimes less successful migrating to Mexico, it is no longer recommended to raise monarchs. Anyone rearing monarchs, even for educational purposes, must have a wildlife scientific collector’s permit from the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry.

The monarch’s Mexico overwintering site was first revealed to the scientific world 50 years ago, in January 1975, and appeared on the August 1976 cover of National Geographic.

The Monarch Population

The North American monarch population fluctuates annually but has been trending downward. This year’s population of western monarchs overwintering in California, released by the Xerces Society in January, was only 9,119. This is the second-lowest number since tracking began in 1997. In the previous three years, numbers were more than 200,000.

Meanwhile, this year’s population at Mexican overwintering sites (estimated from hectares occupied) nearly doubled from last season, but as you can see from this graph, the multi-year trajectory is still declining. The highest number recorded was 189 hectares in 1996-97, representing 380 million monarchs. The lowest number was in 2013-14, only 0.67 hectares or 14 million monarchs.

Where the Monarchs Go