Placemaking is redefining Southern Georgian Bay, creating a unique identity and capitalizing on our assets to ensure a bright future

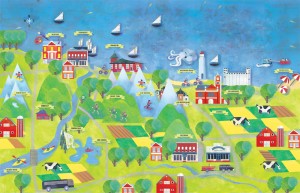

by Janet Lees, illustration by Shelagh Armstrong-Hodgson

Places have power. In an almost mystical way, places can get under our skin, connecting us emotionally to their beauty, their natural wonders, their experiences, activities, culture and people. The very best places are those that keep calling our name, drawing us back, inviting us to settle in and say, “I’m home.” Southern Georgian Bay has this kind of power. And all across our region, examples of placemaking abound, creating powerful affinities that are the building blocks of a sustainable future.

Placemaking is the latest buzzword in urban planning, tourism and economic development circles. It involves capitalizing on a local community’s assets, inspiration and potential, creating public spaces and experiences that promote people’s health, happiness and wellbeing.

According to the Project for Public Spaces, a nonprofit planning, design and educational organization dedicated to helping people create and sustain public spaces that build stronger communities: “Placemaking refers to a collaborative process by which we can shape our public realm in order to maximize shared value. More than just promoting better urban design, Placemaking facilitates creative patterns of use, paying particular attention to the physical, cultural, and social identities that define a place and support its ongoing evolution.”

Narrowly defined, placemaking connotes reimagining and reinventing public spaces as the heart of a community to strengthen the connection between people and the places they share. However, the broader interpretation looks at “power of place” on a broader scale – how a municipality, county or region establishes and conveys its distinct identity, forms connections within the community and draws in “outsiders” to experience the community’s unique attractions. “For me, placemaking is a higher order strategic look at what you want your community to look like that involves economic, community and cultural development,” says Martin Rydlo, Collingwood’s economic and business development director. “It’s a triangle.”

The cultural piece is especially important, notes Rydlo, pointing to Toronto’s Distillery District and Liberty Village as examples of creative and cultural integration within the community’s core. “Those were places that were crumbling locations and the creative and cultural components were key instigators in transforming those communities. So this creative and cultural integration within the community’s core values are driving forces to create this economic, community and cultural development triangle when it comes to placemaking.” Collingwood is in the midst of creating plans to bring all three of these aspects into sharper focus. An economic development plan is awaiting council approval, a community strategic plan is set for approval later this year, and a study by cultural mapping organization AuthentiCity (tagline: “rediscovering the wealth of places”) will form the basis of a plan to ensure the community continues to grow as a cultural hub.

“One of the things that comes out of the economic development strategy is the fact that we are a lifestyle community,” says Rydlo. “That’s not really a huge surprise, but the community is just coming to terms with what that means for the future.” He says tourism is the number one job driver in the area, with tourism and the service industry that supports tourism representing 37 per cent of jobs in the community. “That’s huge,” says Rydlo, “and lifestyle is a huge attractor for that industry, which drives a whole bunch of other things. If you look at the companies that have set up in Collingwood over the past 10 years, you will find that it’s the business leaders who have been coming here as tourists and decided, ‘this is a great place to live and work and I’m going to move my company here.’”

Those businesses in turn hire employees from among the people who come here to participate in the lifestyle the area offers. “That goes right down to

placemaking and continuing to make sure that we hold Collingwood and the South Georgian Bay area as a location that remains true to what people are looking for,” says Rydlo. “In other words, we cannot become a Mississauga or a Brampton. We can make sure that we have streets that flow with minimal traffic. We can have neighbourhoods with sightlines to parks and trails and the mountains. We can have an accessible waterfront, and people going out and enjoying the waterfront.”

In fact, Rydlo sees water as a catalyst and focal point for the entire region. “Whether it’s skiing, farming or tourism, it is all intricately linked to water, so when you think about placemaking you have to remember that water is a key driving element of our placemaking DNA; it is absolutely critical to make sure that gets reflected in everything that happens here.”

It’s no accident, therefore, that Collingwood’s new Art on the Street program, which puts local artists’ work on banners hung from the downtown lamp standards and on Muskoka chairs dotted throughout the downtown, depicts many scenes having to do with water in one form or another.

Water may be part of Collingwood’s DNA, but the town has taken a lot of flack over the years for not developing its waterfront as a focal point for public enjoyment – a placemaking opportunity lost. But that’s about to change, says Rydlo, with a waterfront master plan that will make the most of Collingwood’s waterfront.

“Through the surveys and discussions we’ve had in developing the economic development plan, the waterfront ranks as one of the top three priorities that the community has said the town and the municipality need to work on together with private companies to develop,” he notes, adding, “The key is to make sure that it’s done in a planful way. Not just doing things ad hoc, but knowing what the vision is and chasing after it to create a world-class waterfront. Once we’ve done the community strategic plan, we will kick off the waterfront master plan to put some parameters around what the waterfront is going to look like so that developers and businesses know what the guidelines are under which they can operate.”

Bringing together our physical assets with our cultural and artistic strengths to make downtown Collingwood a more thriving location must be a collaborative effort, and these kinds of collaborations will be critical to the region’s future, says Rydlo.

“If you look at the Distillery District and Liberty Village, it was not just one company saying, ‘we will do this,’ it was a collaborative effort between public and private enterprise that went into creating a vision,” he says. “Collingwood downtown is a great example of a placemaking destination that defines Collingwood, and we can continue working with the Heritage Society, with the BIA, with the town, with the downtown businesses, with the artists and with the special events that come to town to make sure it represents a holistic, thriving community.”

The Craft Beer and Cider Festival held in Collingwood in mid-June is just one example of a well-thought-out event that celebrates the region’s heritage. “I don’t think a general beer festival would fit into the placemaking DNA of the town,” says Rydlo. “However, a craft beer and cider festival is true to our regional DNA with all of the small craft breweries that have sprung up here and all of the apples and cider produced in our region. That is a great example of placemaking in one specific event, which brought in between 1,000 and 2,000 people to experience Collingwood through the craft beer and cider elements that exist here. It’s an example of economic, community and cultural integration.”

A further example of great placemaking through economic, community and cultural integration can be found on Collingwood’s Simcoe Street, which over the past few years has transformed from a ho-hum side street into a cultural hub featuring a state-of-the-art library, a gallery and art school, a new ‘black box’ theatre and a range of trendy restaurants and coffee shops.

“There really wasn’t that much reason to come down Simcoe Street,” says Rick Lex, who, along with his wife Anke has been largely responsible for the revitalization of the area. “It needed some animation, and we felt that putting a variety of creative businesses there, it would create this cluster of like-minded businesses and organizations around creativity that would animate the area and give it an identity and a personality.”

Simcoe Street is now a thriving cultural and artistic enclave, and even mounts its own annual festival called Day of Delight. With the tagline, “Celebrate creativity, Collingwood style,” the street festival, now in its fourth year, features an artisan market, crafts, local food, music, storytelling and theatre.

The funding for the festival comes through ticket sales of the Gaslight Community Theatre productions – an example of the arts supporting the arts.

“The artistic community is very strong in our area, and very supportive and collaborative,” says Lex. “More and more artists and creative people are moving here to this area because of the lifestyle, and the strong artistic community in turn attracts more artists. There’s a little bit of a buzz here, a building of a sense of place and a use of public space around the arts and creativity, which keeps the downtown vibrant.”

Creemore is also focusing on arts and culture to redefine itself. Once a quaint but sleepy town on its way to becoming a rather staid retirement community, Creemore has been reinvigorated as a town that celebrates arts and culture for all ages.

Creemore turned its fall artist studio tour into a full-fledged Festival of the Arts several years ago (now part of the Small Halls Festival celebrating the area’s many historic community halls), and followed up that success by putting on its first Creemore Children’s Festival in 2011. Originally envisioned as a biennial event, the Children’s Festival was such a hit that it is now an annual affair.

Laurie Copeland, who spearheads the Children’s Festival, says it’s all part of a move toward authenticity and enjoying simple small-town pleasures.

“The simplicity of place is apparent in the types of events we have and the businesses that exist and in the floral scape and the streetscape,” she explains. “There’s that sense of authenticity; we don’t try to be anything we’re not. We’re moving away from the idea of something that is quaint because quaint is almost unattainable; it’s not authentic. Creemore today is not so picturesque that it’s unattainable and it’s not so perfect that it’s unpleasing. It’s something that you can really get involved in and something you want to be a part of.”

All of the town’s events centre around the Station on the Green, a not-for-profit community facility modeled after a heritage railway station. The village square also includes a horticultural park and a fountain depicting children playing created and donated by local sculptor Ralph Hicks. It’s a model of placemaking that came about organically and collaboratively, with some residents providing the funds and others like Copeland rolling up their sleeves to make things happen.

“We didn’t have an urban planner come in and say, ‘if you do this, this and this, it’s going to happen for you,’” she says. “It was much more organic than that and much more of a grassroots effort. The business community has worked really hard because Creemore is off the beaten path – you can’t stumble upon it, and it’s not really on the way to anywhere – so there has been a genuine effort to become known in whatever ways that can happen. We can’t change where we are, so we’ve taken where we are and who we are and what we are, and we’ve built on that.”

While Creemore is a success story of reinvention, Wasaga Beach is literally putting its money on the line to re-create itself. The town boasts the longest freshwater beach in the world, yet hasn’t been able to turn that asset into a placemaking bonanza. Town council recently voted to spend $13.8 million to buy seven properties and 28 businesses on Beach Area One – a bold move to try to rescue the town from stagnation.

Wasaga Beach was already struggling when a massive fire destroyed most of the businesses in a pedestrian mall along Beach Area One in 2007, and a developer who purchased the land under power of sale over three years ago had no plans to move forward with developing the properties.

“The fire happened over seven years ago, and although it was sad, it should have been a catalyst in my opinion to put Wasaga Beach back on the map,” says mayor Brian Smith, “but nothing happened, and meanwhile our tourism has gone in the past 10 years from about two-and-a-half million down to probably less than a million now. This has always been a tourist town; it’s our one and only industry – always has been and probably always will be – and we’ve got to find ways to build on that in order to be successful.”

With no downtown to speak of, and no attractions beyond the beach itself, there is nothing to keep tourists in the town if the clouds roll in, and nothing to keep them coming back for more than a day trip.

“Tourists come to the area for something to do; there has to be something to attract them, but beyond that there has to be something to keep them here,” explains Smith. “In Wasaga Beach people used to come here in the summer for a week or two, and now they come for the day and leave. When the arcades disappeared and the midway disappeared, and all of those unique and small businesses were gone and nothing new was created, there was nothing to keep them here. If it rains, they go home.”

It’s a case of placemaking in reverse, and the result is a town that has floundered and lost its way. With council’s decision to buy up the beachfront properties, Smith would like to see the town rebuilt to once again capitalize on its power of place. “By creating and redeveloping a new downtown and a beachfront with shops and boutiques and restaurants and tourist attractions – maybe another water slide again or a water park, maybe a Great Wolf Lodge, or you name it – they’ll come and they’ll stay again. I’m a big believer that if you build it they will come.”

To facilitate the changes, the town is hiring a director of economic development and tourism as well as a grants writer to apply for funding. Wasaga Beach’s special events department has also been revamped to bring in large events that will attract tourists and locals.

“We’re in the process now of putting all of the pegs in the right holes so that we can start to make it a reality,” says Smith, who is optimistic about the possibilities. “We are experiencing something here in Wasaga Beach that most towns never get to experience a second time, and that’s a clean canvas. There are very few communities that ever that get that second chance, so we can learn from our mistakes of the past, and learn from the positives of the past as well, and ensure that we take the right amount of time, get the right people in the right places, and work in conjunction with the private sector to re-create what I believe will be one of the most beautiful communities in the world.”

Working from a blank slate does have its benefits, and Blue Mountain Village, arguably the best example of placemaking in the region, is a case study in creating power of place from scratch.

“For the Village, placemaking is the intentional design of our public spaces to inspire togetherness and healthy activities in a safe and beautiful environment,” says Patti Kendall, director of marketing and events for Blue Mountain Village, noting that the parent company’s development arm is branded Intrawest Placemaking. “When done well, it becomes a platform for developing unique and authentic experiences.”

Creating Blue Mountain Village from the ground up allowed Intrawest to build in placemaking elements along the way, including a village square with a bandstand and fountain, creeks, a pond, and a recently opened waterfront promenade – all with Blue Mountain as the ultimate placemaking attraction. In addition to shopping and dining, the Village offers live entertainment, arts and craft shows, movies, a climbing wall, a world-class putting course, a zipline and ropes course, an aquatic centre and a mountain coaster ride. Festivals and events celebrate everything from jazz and salsa to apple harvest and Elvis.

“The Village creates a meeting place for celebration, reflection or just time together with family and friends,” says Kendall. “That was the original vision, and our research reflects that that is what people are looking for.”

But not only did Intrawest go beyond simply creating a resort modeled after an old Ontario town, adding a gathering place, throwing in some fun activities and putting on events – it expanded its placemaking identity to encompass the entire region.

“In the beginning we needed to get people from Toronto and greater Ontario to come to the Village and invest in the lifestyle of the Village; in other words, buy real estate,” notes Kendall, “but then it grew and matured to the point where we wanted people to come and explore the region and the lifestyle, to give them a reason to keep coming back. And if they’re only at the resort, they may not feel compelled to come back if they feel they’ve done everything.”

With this in mind, Kendall looked at what sets our region apart and came up with the idea for the Apple Pie Trail, which she describes as “a celebration of this area as the largest concentrated apple-growing region in Canada.” Partners, collaborators and supporters throughout the region quickly got on board, and over the past seven years the Apple Pie Trail has mapped out 37 “stops” across Southern Georgian Bay, featuring not just restaurants and purveyors of apple treats, but also artists and artisans, galleries, museums, wineries, breweries and shops. There are also Apple Pie Trail Adventures, including winter snowshoeing and wine tasting, and a pedal and paddle adventure that was named an Ontario Tourism Signature Experience.

The Apple Pie Trail “connects all the key tourism destinations but it’s also that ‘locals know’ product,” says Kendall, adding it has attracted a lot of attention internationally from as far away as China and Brazil.

Taking such a broad view of placemaking means that what’s good for Blue Mountain Village is good for the entire region economically.

“We work every day with regional partners, and what’s really exciting is the feeling that we are all working together,” says Kendall. “We’re stewards of this place, and the future is to maintain the integrity of what we’ve built and to continue to work together and collaborate with a wider range of partners throughout the area to build on what we’ve developed, to make sure it’s easily communicated to locals and visitors alike, and to create those experiences that will bring people back again and again.”

At the other end of the region, Thornbury and Meaford are working to attract more tourists, businesses, families and retirees, building on their strengths and their power of place to create healthy, demographically diverse and sustainable communities.

Like Collingwood and Wasaga Beach, Thornbury and Meaford are focusing on water as their most valuable asset. Thornbury, with its historic harbour on Georgian Bay, its river, dam, fish ladder and millpond, has water literally running through its identity. On any weekend summer day, the bridge across the Beaver River is packed with people leaning over the railing to view the dam and the fish that make their way up the adjacent fish ladder to spawn in the millpond above.

The town saw the fish ladder as its best placemaking opportunity, so, with funding from the regional tourism organization, hired a consultant to investigate how to build a unique experience around the fish ladder.

“The consultant came back and said we needed to not just placemake around the fish ladder but to look at Thornbury as a whole while using the fish ladder as a unique feature that enhances the experience of the town,” says Elizabeth Cornish, communications and economic development coordinator. “Thornbury is a harbour town, and we also have the river and the dam as well as the fish ladder, so the idea is to focus on the role of water in the history of the community as a larger thematic piece by creating a loop that would allow people to go from the fish ladder down through the pathways that we have, across the trestle bridge to the harbour and back up Bruce Street. These are the things that we want people to experience here.”

Cornish says the fish and water theme will begin appearing around the town, on signage and placement of art throughout the town. There is also a movement to utilize the greenspace between the new town hall and the river. “That could be an incredible gathering space for the town, so we’re looking at how we can enhance that space. It’s all around budget and funding, but it’s very exciting.”

While Thornbury’s harbour is currently underdeveloped and underutilized, Meaford has had great success with placemaking around its harbour and waterfront. “The harbour itself is a busy, busy place – many of us say it’s the prettiest harbour in Southern Georgian Bay – and we’re fortunate to have so many kilometres of waterfront,” says Meaford mayor Barb Clumpus. Next to the harbour is the Harbourfront Pavilion, home to Sunday evening concerts, Friday afternoon farmer’s markets, and a popular spot for weddings and photos. The pavilion is also a focal point for the town’s immensely popular Scarecrow Invasion, which along with the Apple Harvest Craft Show, brings in busloads of people and almost double the population over the course of a single weekend.

“There are so many activities centred on our waterfront because it is so connected to our downtown area,” says Clumpus. “Our main street is literally a block away from our waterfront area, so there’s a natural connection and that is a huge advantage.”

The town recently completed a strategy for the next phase of harbour and waterfront development that proposes, among other things, building a commercial/retail area along the harbour wall and recreating Meaford’s historic train station in the area of the harbour.

“We’re really trying to connect all of the businesses and opportunities around the harbour area,” says Clumpus, adding Meaford Hall, the town’s cultural and artistic centrepiece, located a block away from the water, is “absolutely key to that. It’s an iconic statement for our municipality, and a hub for our community.”

Whether it’s water, apples, arts or culture, placemaking is defining – and redefining – what makes Southern Georgian Bay unique, authentic and attractive, continuing our evolution from a shipbuilding and industrial area to a lifestyle and tourism mecca.

As Clumpus sums it up: “We love this area because it speaks to us, and it speaks to us because of what we do here.”

Creemore’s Laurie Copeland agrees that our region’s power of place ultimately rests in its ability to create strong emotional bonds. “It really is about keeping things close to the heart,” says Copeland. “A lot of people go into communities and try to take possession of those communities, and I think what’s unique here is that it’s the community itself that kind of takes possession of you and ties you to it. You’re not sure who or why or what it is, but all of a sudden it has this hold on you that really is more than the sum of its parts.” ❧