The name we give to things matters. Awareness and esteem start with reclaiming the word.

by Jessica Wortsman // Photography by Jessica Crandlemire

“What’s a vulva?”

That’s a question many people can’t answer, including more than 70 percent of women, according to a U.K. poll. It’s no wonder, then, that we rarely use the word “vulva,” even though it’s usually what we’re talking about when we say “vagina.” That, and the fact that some people find the word itself deeply unsettling. For them, there’s a hotline offering exposure therapy, where callers listen to the word “vulva” on repeat until it feels less weird. I kid you not.

Vulva is the name for the female external genitalia, including the labia, clitoris and urethra, and the near erasure of the word from our vocabulary says a lot about our overall attitude toward women’s sexual anatomy—ignorance and shame.

Local artist Fran Bouwman aims to change that, once again using her creativity to tackle a challenging topic. More than an accomplished sculptor, Bouwman is also an educator who’s worked extensively with Indigenous communities in the Far North, as well as a musical comedian known for her frank and feminist performances under the alter ego Franny Wisp & Her Washboard.

Bouwman’s newest initiative, the Viva La Flying Vulva Positivity Portal (vivalaflyingvulva.com), brings together all of her passions and skills—advocacy, art, storytelling and education. Combining online and offline activities, the hub both celebrates and helps educate about the vulva. The website showcases Bouwman’s artwork, vlog and vulva merchandise, as well as links to other vulva-related art and events. The site will also host online courses and opportunities to register for in-person workshops.

The seed for this project was planted several years back when Bouwman discovered a fallen tree with an organically formed vulvar cavity at its core. She turned that unusual find into a huge vulva sculpture that garnered a variety of reactions, many positive, others less so.

There was the male art tour committee member who found the sculpture vulgar and disgusting, and later, the local gallery whose owners asked her to remove the piece from their space only weeks after putting it on display, claiming it attracted “riffraff” to the window. Her work clearly touched a nerve, and though she rarely shied away from provocative subject matter, that negativity elicited in her unexpected feelings of shame.

“It really stressed me out. It did. I also felt a bit sick to my stomach. Like I was doing something wrong,” Bouwman says.

The Name of Shame

The name we give to things matters. Names help us identify and connect to things and are often the wellspring from which we form our opinions of them.

We may avoid using the word “vulva,” but we have plenty of other names for that part of the anatomy and none of them are very accurate or nice. Popular euphemisms range from cutesy (vajayjay) to rude (twat), to disgusting (nope), and even downright nonsensical (hoo-ha, foof, minky—what?).

Then there are the anatomical names for our body, chosen by the ancient Greeks and traditionally given in Latin. Most names were descriptive so as to be easy to remember. For example: the part of the brain responsible for emotion, memory and learning was named the hippocampus—Latin for seahorse—because of its small, curved tubal shape. The word “penis” translates to “tail” and “gonad” (a.k.a. testicle) translates to “offspring” or “seed.” Makes sense, right?

It’s pretty telling, then, that many of the anatomical names given to female genitalia expose the ignorance and patriarchal attitudes of the time.

Exhibit A: The word “vagina” comes from the Latin word “sheath,” meaning the covering of a sword (i.e., a penis). In other words, the vagina is but a penis accessory.

Exhibit B: The anatomical term for the vulva is “pudendum,” which in Latin means “thing to be ashamed of.” Yeah, you read that right.

But the vulva wasn’t always considered shameful. In fact, some of the earliest and most prolific archeological imagery is of the vulva (called yonic iconography) and dates all the way back to the Paleolithic age. From prehistoric vulva engravings on cave walls, to ancient Sumerian poetry celebrating the beauty of the goddess Inanna’s vulva, to the sheela na gig stone carvings from the Middle Ages of women holding open their enlarged labia, evidence of the vulva’s significance has been found throughout history and across cultures. Indeed, the prominence of yonic art and artifacts suggests to most scholars that female fertility and sexuality were once sacred, and that the vulva was seen as the portal to life.

It was only with the move away from goddess worship and toward monotheism and patriarchal societies that the vulva was stripped of respect and power. We see it disappear from art during the time of the ancient Greeks and Romans, who were much fonder of the male form, and by the time Freud, the father of psychology, eventually got his say, the vulva was reduced to a second-class sexual organ pleasurable only to the mentally immature or unwell.

“I find it a very fascinating concept that you can live a life as a woman and just not really be in relationship to an exceptional piece of your anatomy.”

Fran Bouwman, artist, comedian and educator.

““There’s so much variation in vulvas. Vulvas come in all shapes and sizes.”

Lisa Pelletier, MSc RP RMFT

Dirty Delusion

“I don’t want to call myself the vulva police,” laughs certified sex therapist Lisa Pelletier—whose practice, HeartFlame, is located in Collingwood—though she says she can’t help but correct people when they mistakenly refer to the vulva as a vagina. Which is most of the time.

When asked why the word isn’t used more often, she points to sex education classes in school. Traditionally, she says, the curriculum is focused on the internal reproductive system featuring that iconic ram’s-head-with-horns illustration of the uterus and fallopian tubes, and rarely includes correct and comprehensive information about the external female genitalia.

As well, she says, women just aren’t as familiar with their sexual organs because they’re hidden between their legs. “It isn’t like men’s genitals—out front and centre. You have to spread your legs to see your vulva properly.” Something, she points out, many women just don’t do.

The vulva also serves dual functions that can sometimes seem at odds. On the one hand, it’s got important, and often messy, work to do like elimination (urine, blood and discharge) and childbirth. But the vulva also likes to play. Within its folds lies a complex network of sensitive nerve endings. The clitoris, whose external nub is found just under a hood at the top of the labia minora, is thought to contain more than 10,000 nerve fibers, making it almost twice as sensitive as a penis. Its only function is to provide pleasure.

“The vulva is where all the fun is going on,” says Pelletier, but people can get caught up in this idea that it’s dirty.

In fact, Pelletier conducted her own informal field study and headed to the pharmacy to count the number of genital hygiene products marketed to men and women. What she found likely won’t shock you.

There were all sorts of cleansers and deodorizers for women’s genitalia. “There were shelves of them,” she says, “as though regular soap and water aren’t strong enough to properly clean the “dirty” vulva/vagina.”

It’s a notion that couldn’t be further from the truth. Harsh cleansers and fragrance actually irritate the sensitive vulva, while the vagina is its own little self-cleaning oven, using natural secretions to maintain a healthy pH balance.

Unsurprisingly, there were absolutely no products marketed to men’s genital hygiene. “There’s no shelf for men,” says Pelletier. “There’s no cock-and-ball cleaning products. That says something. Women are dirty. That area is gross. But not men.”

As well, says Pelletier, porn and social media present a very narrow representation of female genitalia. In reality, vulvas and their parts are incredibly varied, but many women worry theirs is not “normal.” This has a huge impact on women’s sexual satisfaction.

“It’s very hard to go from this dirty place that’s shameful to a place of enjoyment and celebration.” If we aren’t comfortable with our own body parts, she asks, can we really be comfortable sexually? If we don’t name it or look at it, do we touch it? Do we let our partner look at it and touch it?

Barbie Girl

Bouwman’s project was also fueled by the revelation that labiaplasty (the surgical reduction of the labia minora) is among the fastest-growing cosmetic procedures. Though a small percentage of those who choose this surgery say their “outie” labia make sport and sex uncomfortable, the vast majority do it for aesthetic reasons. The desired look, often referred to as “Barbie Vagina” (though Barbie Vulva would be more accurate), involves trimming off all visible parts of the inner lips so the vulva resembles a smooth mound.

Like most feminists, Bouwman believes women have the right to choose what they do with their bodies but says she’s wary of plastic surgery. “It’s a money-making industry preying off of female insecurity.” One only has to take a look at the rhetoric on their websites to see what she means.

“The lips of the vagina are trimmed in order to improve its aesthetic value.”

“Look good in yoga pants with a designer vagina.”

“Reduce the size of your labia minora and feel confident again.”

Bouwman is doubtful this surgery can deliver any real and lasting confidence—self-esteem, after all, is an inside job. The real issue? Women’s dissatisfaction with their vulvas. A recent poll shows that of 3,600 women surveyed, almost half were unhappy with either the size, shape or colour of their vulva. Bouwman wonders whether plastic surgery would be as popular if women weren’t constantly told they’re not good enough as they are.

“How far are we going to go?” she asks. “What are we not going to cut up?”

Big Vulva Energy

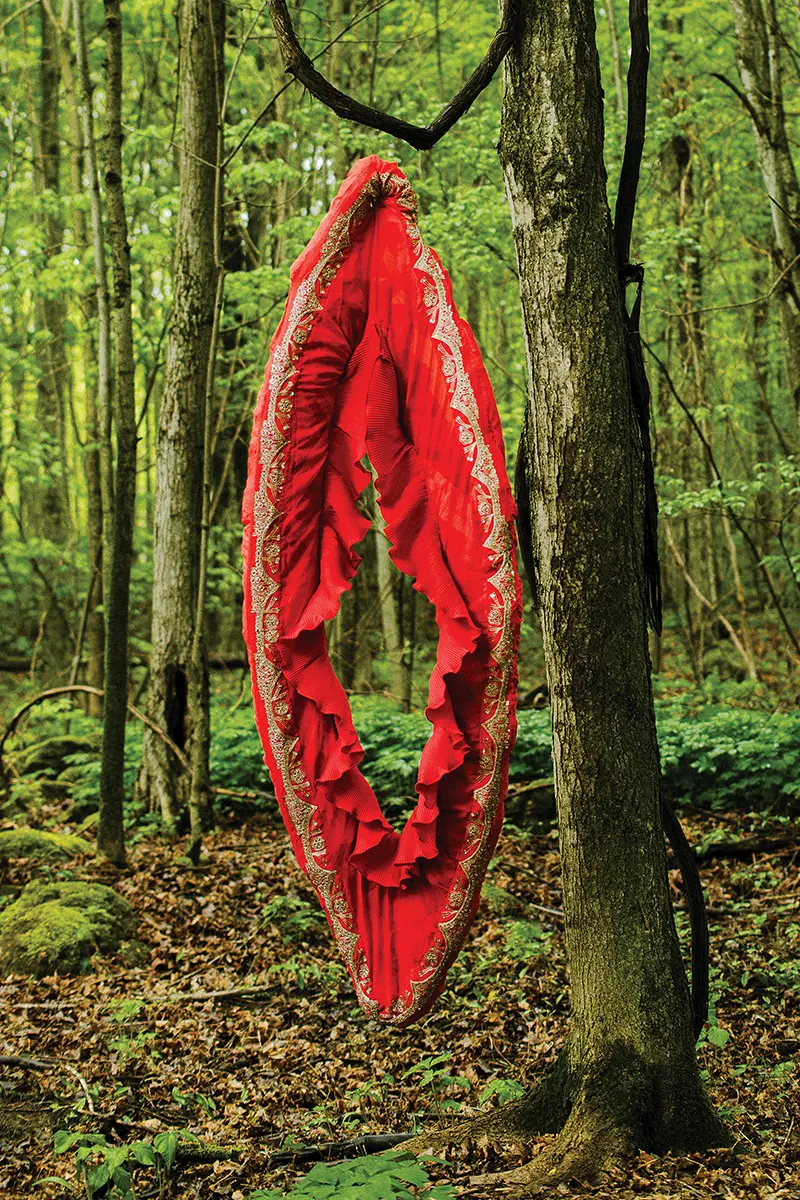

At the Viva La Flying Vulva launch on April 20 at Mantra Yoga Studio in Thornbury, attendees experienced Bouwman’s collection of winged vulva sculptures, each a tribute to the beauty, power and diversity of the vulva.

Most conspicuous was the six-foot-tall fabric vulva hanging from the centre of the room through which giggling guests were encouraged to throw bean bags tagged with words of positivity like “powerful,” “unique” and “sacred.” The bejewelled and ruffled stuffed red vulva was sewn together by Bouwman’s 86-year-old mother Willemina and was Bouwman’s cheeky way of putting people at ease by having them play with the very object of their discomfort.

“One of the things that Fran is so good at is making challenging topics easy to talk about,” says Marni Sandell, a long-time colleague and good friend of Bouwman’s. “It’s hard for people to go there and have those conversations, but when you can bring lightness and fun to a space like that, it just instantly makes people more comfortable.”

And there was no shortage of conversation among the guests. Some had questions, others had opinions, a few even had reservations, but this time any negativity was taken in stride. “Diverse opinions are really good for dialogue,” says Bouwman, smiling. And dialogue is key.

The consequences of perpetuating shame and silence around the vulva are too dire. How do we learn respect for a body part we’re not taught about in school? What pleasure can come from a place deemed shameful? How can we ask a doctor to treat a body part we can’t even name? The first step, surely, is to reclaim the word.

“It’s about awareness that I hope builds into esteem,” Bouwman says, of her goal for the positivity portal, “so that women can feel more in tune, more empowered, more confident and more curious about that part of their anatomy.”

Call It What It Is

Let’s define two very important terms (so there’s no more confusion).

Vagina

The canal that extends between the cervix and the outside of the body, completely internal.

Vulva

The external female genitalia comprising the mons pubis, labia minora, labia majora, clitoris, clitoral hood, urethra, vestibule, Skene’s glands, Bartholin’s glands, and the vaginal opening.