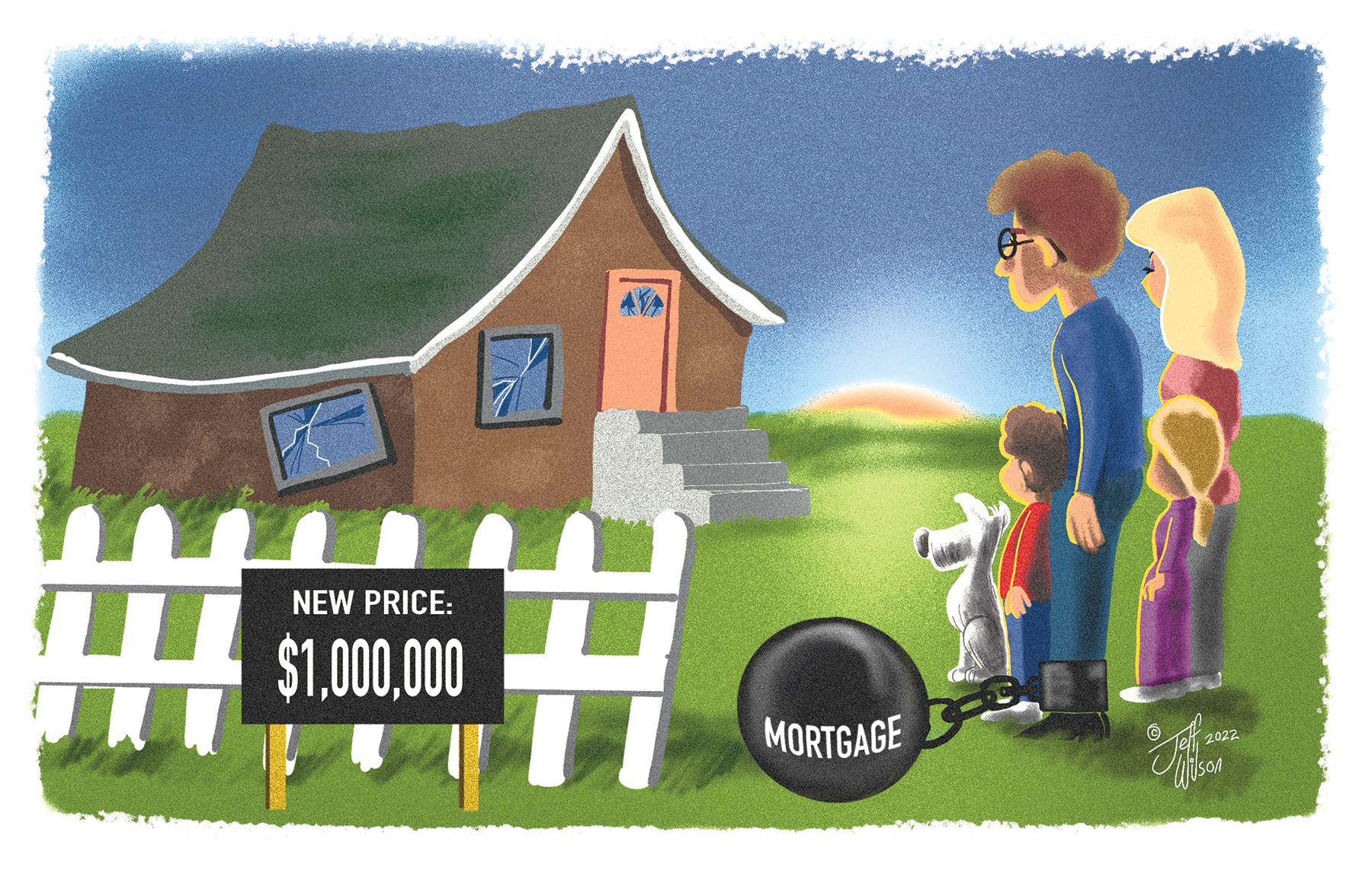

Whether you’re buying or renting, housing in the Georgian Triangle is increasingly out of reach.

by Dianne Rinehart // illustration by Jeff Wilson // photography by Roger Klein

Kirsten Schollig had been living in her lovely, brand-new townhouse on George Zubek Drive in Collingwood for about a year with her boyfriend when they received notice that their landlord was selling.

And no wonder. The owner had purchased it as an investment in February 2019 for $424,284. Two years later he sold it for $708,000—way, way above his asking price. Then a year later, the new owners sold it again for $976,500.

“I couldn’t blame him,” says Kirsten, a photographer whose studio, Captured by Kirsten, specializes in weddings and brandings.

What ensued was a long and stressful search for housing that she says would ultimately end with the breakup of her four-year relationship.

At first the couple couldn’t even find an affordable apartment to rent, so Schollig went to Wasaga to live with a girlfriend for a month and a half while she searched.

She finally found a condo to rent, but the landlord would only give it to her for three months. By the time she found a one-bedroom condo for $1,350, she had moved three times.

Schollig is not alone in her search for affordable housing.

Whether you are buying a home or looking to rent in the Collingwood region, the challenges are formidable.

According to the Canadian Real Estate Association, the average selling price of a home in Collingwood in January 2022 was $1.1 million. That’s up a whopping 78.5 percent from January 2020.

Compare that to Toronto where the typical home price rose 52 percent over the past two years. Meanwhile, active listings are down 24.3 percent for the region, which can only lead to more bidding wars.

“One would anticipate that the number of sales could be much higher with the demand surging throughout the area,” says Chuck Murney, president of The Lakelands Association of Realtors.

But, “Prices might not be as affected were there more choice in housing and not the multiple offers driving up average home Housing inventory is being squeezed on two sides, he notes. People aren’t selling because they feel there is nowhere for them to go, and the town is delaying new builds because “township infrastructure has been pushed to the max.”

And real estate agents working in the area do not expect it will slow down anytime soon.

“People want to be here—they don’t need to be here,” says Giovanni Bonni, an agent with Bosley Real Estate in Thornbury. “And it’s not just the retiring demographic moving up, it’s the younger generation too.”

“There’s a lot our communities offer and it’s a well-balanced healthy lifestyle with like-minded people. Who wouldn’t want to live here?”

But could the region be killing the goose that laid the golden egg?

Way back in 2018, a study conducted for the region, called the South Georgian Bay Tourism Labour Supply Task Force, found that prices were already outpacing salaries.

Indeed, the income required to buy a home was “almost double the region’s median income.”

According to the Canadian Real Estate Association, the average selling price of a home in Collingwood in January 2022 was $1.1 million. That’s up a whopping 78.5 percent from January 2020.

And it’s gotten worse, much worse.

An Affordable Housing Task Force, organized by the Town of Collingwood, reported last November that: “The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated housing struggles for the Town of Collingwood from the influx of people wishing to relocate to the area from large urban centres, inflating housing costs as well (for) existing residents trying to live within their means with an appropriate and affordable place to live.”

The result, housing—rental or purchased—is out of reach even for relatively well-off residents in this area, the task force reported in November.

Even high-income earners—households earning $190,000, for example, in Collingwood—cannot afford the average home price in town of $1.1 million, based on the definition of housing affordability used by the task force, which is that 30 percent of income is spent on accommodations.

Meanwhile, the highest-income renters—those with a household income of at least $96,335—are the only ones who can afford rental units that cost $2,408 per month.

But where are those units to be found?

When Richard Smith and Stephanie Ellis-Smith went looking for a Collingwood rental to live in while they built a new home to replace an old cottage in Wasaga Beach, they ran into landlords who would only accept seasonal rentals.

“Some of these seasonal rentals were $45,000 for four months or so,” says Smith. “We needed something for a year.”

Smith, who works in healthcare technology, says there were queues for a unit the minute it hit the market, and he wondered whether he was supposed to get into a bidding war to get a rental home.

It took three months of constantly watching for rentals to finally land a three-bedroom condo that he and his family could afford.

None of this is good for businesses in Collingwood—upon which its tourism-based economy depends.

High rents mean local employers cannot “attract and retain workers, with some employers incurring costs in order to house or transport their workers,” the Housing Affordability Task Force noted.

And for would-be employees who want to buy a home, the search is just as tough. That’s because seasonal and retirement buyers can pay prices unrelated to local jobs and incomes.

“As a result, area businesses are concerned; some have had to curtail operations for want of workers,” the task force reported.

Tell that to Travis Barron, the head chef for Northwinds Brewhouse and Kitchen, which has restaurants in both Collingwood and Blue Mountain.

“There have been staffing issues ever since I moved up here 13 years ago,” he says. “The town has done squat about it.”

He says the brewhouse has trouble attracting staff because potential employees can’t find a place. And he says the housing shortage affects business owners who have to pay higher wages to attract staff, and so must charge higher prices to customers to cover their costs.

Barron is lucky enough to own his own home. But he notes he was fortunate to get into the market six years ago. “I probably couldn’t get in today.”

It’s not just restaurants that are experiencing staffing problems. “Gas stations, convenience stores, you name it,” he says.

So, the solution? Barron doesn’t know. “What developer wants to make cheap homes?” he asks.

That said, he notes wryly that while there’s not enough accommodation for staff in town, there “are lots of places” for visitors to stay. And the housing market is skewed in another way.

“Collingwood has added only 213 new rental units since 2008,” the task force found. Those account for only six percent of all housing completions in the town.

High rents mean local employers cannot “attract and retain workers, with some employers incurring costs in order to house or transport their workers.”

Hello? What else is being built?

Too many single-family homes, Mayor Brian Saunderson says.

“The only way to grow is to increase density,” as the task force suggested, he says. Progressive Conservative party in the upcoming provincial election, says that municipalities cannot solve the housing crisis themselves. It will take a concerted effort from all three levels of government.

Another solution might be to adopt one of the recommendations from the housing task force and prohibit short term rentals to increase the overall rental stock in the municipality.

But that has not been adopted yet, as both Schollig and Smith found.

But the housing crisis isn’t just tough on those looking for a place. Tenants who have a home or unit that they can afford are anxious that they may be forced to move if their landlords decide to cash in on rocketing real estate prices, as Schollig’s did.

One young single mother, who didn’t want her name used for this article, pays $1,675 for a two-bedroom unit in Thornbury. “If we ever lost this place I would have to move out of town,” says the woman, who runs her own business.

Bam (Wesley) Kidd, a musician and landscaper, understands that fear. He had a landlord sell a home out from under him. He had signed a lease for $1,500 a month, and four months into it the owners decided to sell. He knew his rent would go up.

So Kidd, who is a member of the Unity Collective that wants Collingwood to be “free of barriers to inclusion,” put out an S.O.S. on social media and ended up finding a home to rent for $1,500 that accommodates his office, music studio, and his trucks.

“I won’t be going anywhere,” he says.

The home, owned by Carruthers and Davidson Funeral Home, had been vacant for five years, but a friend knew about it. He approached the business and got it. “The house I was in was taken from me. Karma brought it back,” he says.

Bam was fortunate. But others are concerned.

If it’s any consolation to them, the town has acted on the latest affordability report by putting $250,000 into an affordable housing reserve to look at strategic objectives in land use, and set aside money to hire an affordable housing specialist, Mayor Brian Saunderson says.

But he admits: “We still have a lot more to do.” Indeed.