Can bikes and cars coexist?

by Laurie Stephens

photography by Doug Burlock

The picture sent shockwaves through the cycling community and beyond. It depicted a man in cycling gear being handcuffed by an OPP officer on a rural road as other riders looked on.

According to news reports, the rider had refused to identify himself to the officer, who had stopped the group for a traffic infraction that was apparently caught via aerial surveillance of the group. Some local cyclists accused the local OPP detachment of deliberately targeting cyclists, and not for safety reasons.

The image and the ensuing widespread coverage of the incident – it even sparked a story in the Toronto Star – has triggered a healthy conversation in the Southern Georgian Bay area about how to address the tension that exists between drivers, cyclists and even law enforcement in the region.

“The incident highlighted confusion about what is or is not acceptable, and has led to a better understanding and improved relations with the OPP,” says Noelle Wansbrough, president of the Collingwood Cycling Club.

It has also led to increased efforts to make cycling routes safer and to educate riders and drivers about how to safely share the road. And that’s a good thing, because cycling in the region is exploding in popularity. Where 15 years ago dozens of cyclists graced our Grey and Simcoe county roads on weekends, they now number in the thousands. And the cycling phenomenon extends well beyond the weekend road warriors.

More and more people are using the existing road and trail networks and identified city street routes to bike to work, run errands or just get out into the fresh air for some exercise that provides terrific cardio benefits while being easy on the joints.

Meanwhile, cycling events and competitions are gaining in popularity, bringing an increasing number of participants and spectators to the area, in turn spawning new events that provide an even greater draw.

Why the upsurge in interest in cycling in our region? It’s simple, says Wansbrough, who owns Pedal Pushers Cycling, a company that offers bike clinics, coaching and tours for all levels of cyclists.

“This area – Collingwood and The Blue Mountains – is well-known, not just in Ontario, as a cycling destination,” she says, “it’s known everywhere now. From a marketing standpoint, it’s good for business, it’s good for tourism, it’s good for small business owners, restaurants, hotels, everything.”

Certainly the region has an abundance of opportunity for every type of rider: hills and valleys on picturesque gravel and country roads; a substantial trail network that is relatively flat; mountain bike trails on the escarpment; a downhill course at Blue Mountain; and an increasing number of in-city routes designated as safe for bikes and e-bikes.

“I think a really unique aspect about cycling here that other places don’t have is the prominence of lots of nice villages, some fantastic vistas and valleys that get you onto some pretty unique roads and settings near the water,” says Martin Rydlo, Collingwood’s director of marketing and business development. “Research also shows that cyclists like beaches, hiking and canoeing. Well, guess what? We’ve got all of that around here, too, so it’s a pretty ideal setting for a central cycling area in Ontario.”

There’s also been significant growth in the use of cycling as active transportation, says Dean Collver, Collingwood’s director of parks, recreation and culture. “We’re seeing more bicycles on trails, people are getting to the grocery store or back and forth to work because it provides for an active lifestyle and it’s an economical way to move.”

Of course, being a cycling hotspot comes with consequences, both positive and negative. On the plus side, more people are out and about, getting exercise and using bikes as an economical means of transportation, leaving their gas-guzzling cars at home.

There are social benefits as well. It’s not uncommon to see groups of cyclists enjoying a leisurely weekend outing on some part of the 34-kilometre-long Georgian Trail that stretches from Meaford to Collingwood. The growth of cycling events of all kinds in Southern Georgian Bay means more cyclists are coming together to form a community of competition and drawing more spectators who simply enjoy watching cycling events.

The social aspect of belonging to a cycling club is also a significant motivator, says Wansbrough, who has more than 20 years’ experience in competitive cycling and coaching. A club ride can turn into a community affair, with family and friends taking part, a local business sponsoring the ride, and at the end of the trek, pizza and beer at a local restaurant.

“I’ve had people come up to me and say, ‘The Collingwood Cycling Club changed my life. I have all these new friends, we go on trips to Europe now.’ It snowballs into a whole other socialization, other than just on the bike.”

The economic spinoffs of the region’s cycling boom are obvious as well. While municipal statistics on cycling’s impact are difficult to find, Ontario By Bike, a non-profit organization that promotes cycling throughout the province, has compiled some revealing numbers from authoritative sources.

In 2016, the latest year tabulated, there were 1.6 million cycling visits to Ontario and these cyclists spent $517 million in the destinations they visited. Cycling visitors generally spend more on average per trip than other visitors – $317 per trip for cycling tourists compared to $186 per trip for total visitors in 2016 – and the average number of nights spent on cycling visits was 4.4, slightly above Ontario’s total visitor average of 3.4 nights.

In 2018, the counties of Bruce, Grey and Simcoe – designated as Regional Tourism Organization 7 (RTO7) by the Ontario Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport – hosted 14 per cent of all Ontario cycling events, tied for first with RTO6 region of York, Durham and Headwaters.

And, as of Feb 2019, there are 165 businesses in RTO7 that are part of the Ontario By Bike Network, a registry of “bike-friendly” businesses. A business is designated “bike-friendly” if it meets certain criteria, including having such amenities as bike racks or secure bike lockers, free water-bottle fill-ups, cycling route maps on-hand or basic bicycle repair toolsets.

Province-wide, this network of bike-friendly businesses has been growing by 37 per cent annually as businesses realize the benefits of attracting customers who typically spend more than others.

General population growth means that not only are there more cyclists on the roads, there are also more vehicles. That can lead to an escalation of tensions between cyclists, drivers and law enforcement officers.

Louisa Mursell, executive director of Ontario By Bike, says one of the most striking statistics she has seen is the rise in the number of recreational/leisure types of cyclists who are taking day trips or overnight trips to cycling hotspots. “You see a lot of people out there with their road bikes and their spandex, and the reality is, the bigger market is the average Joe. So, it’s really exciting to see more of those types of people taking part in cycling activity.”

But with such popularity and growth come certain challenges, particularly on highways and county roads.

General population growth means that not only are there more cyclists on the roads, there are also more vehicles. That can lead to an escalation of tensions between cyclists, drivers and law enforcement officers, as the well-publicized incident last summer dramatically illustrated.

From cyclists, you will hear anecdotes of drivers trying to force them off the road while passing, or moving onto a shoulder after passing, kicking up gravel that hits the riders. From drivers, you will hear stories of cyclists not moving over to ride single file when a vehicle wants to pass, or cyclists cruising through stoplights and stop signs without stopping.

Surprisingly, Ontario Provincial Police incident reports show virtually no increase in collisions involving cyclists and motor vehicles: there were eight in 2016, 10 in 2017, and eight in 2018. Of the 26 incidents, 16 were classified as “no injuries” and the remaining resulted in minor injuries.

Those stats are remarkable given the growth of traffic of all kinds on the roads, not to mention the potential for calamity when a two-tonne motor vehicle collides with a bicycle.

“Sharing the road is certainly an important part for motorists, but for cyclists as well,” says OPP Constable Martin Hachey. “Let’s face it: your safety, as a cyclist, should be your number one priority because when you’re on the roadway, even if you get into a collision with a sub-compact vehicle, you’re going to unfortunately probably suffer some injuries, possibly serious and maybe tragic at some point.”

Large trucks on the road present another challenge, as they take longer to slow down and speed up, and have a more difficult time trying to pass.

Seeley and Arnill Construction is a family-owned road and bridge-building contracting business that supplies aggregates which have been used for bike lanes in the region. In 2017, the company constructed paved bike shoulders for Grey Road 119 from Banks to Ravenna.

“That was about 70,000-80,000 tonnes of material, 3,000 truckloads that was hauled there for cyclists,” says Blake Arnill, one of four brothers that manages the fourth-generation business.

While Arnill appreciates the business that comes from bike lane construction, he says his trucks carrying loads of up to 36,000 kilograms of aggregate have encountered many cyclists who lack common courtesy when a heavy truck approaches. They fail to move over, and that can result in “dumb passes” or other drivers behind a slowed truck tail-gating too closely.

Even when building the shoulders from Banks to Ravenna, Arnill’s truckers delivering the aggregate along Grey Road 2 would get “endless grief” from cyclists who complained that trucks made the route unsafe. “Maybe something they could look at is, make them get a licence plate for their vehicle,” he says. “They are driving on taxpayer-funded roads, they don’t have licences and they want the rights and the rules of the road, but they don’t want to abide by them.”

But most cyclists are taxpayers too, and many of them are drivers as well. What’s apparent in the heated rhetoric are entrenched attitudes that can inhibit positive conversations about how to make the roads safer for all users.

In Ontario, the Highway Traffic Act is clear: a bicycle is defined as a “vehicle” in the Act and therefore has every right to be on the road.

Steve Varga, vice-president of the Collingwood Cycling Club and also a lawyer, says tensions arise on the road in part because the Highway Traffic Act (HTA) is vague, and direction is lacking from the Ministry of the Attorney General and the Ministry of Transportation.

“The problem is the HTA doesn’t deal with group cycling,” says Varga, whose members ride in groups of up to 12 on low-traffic country roads on weekends. “The OPP are trying to figure it out by asking for guidance from the AG’s office and we are all waiting for a response from them. In the meantime, the police and cyclists are on hold as far as anything conclusive.”

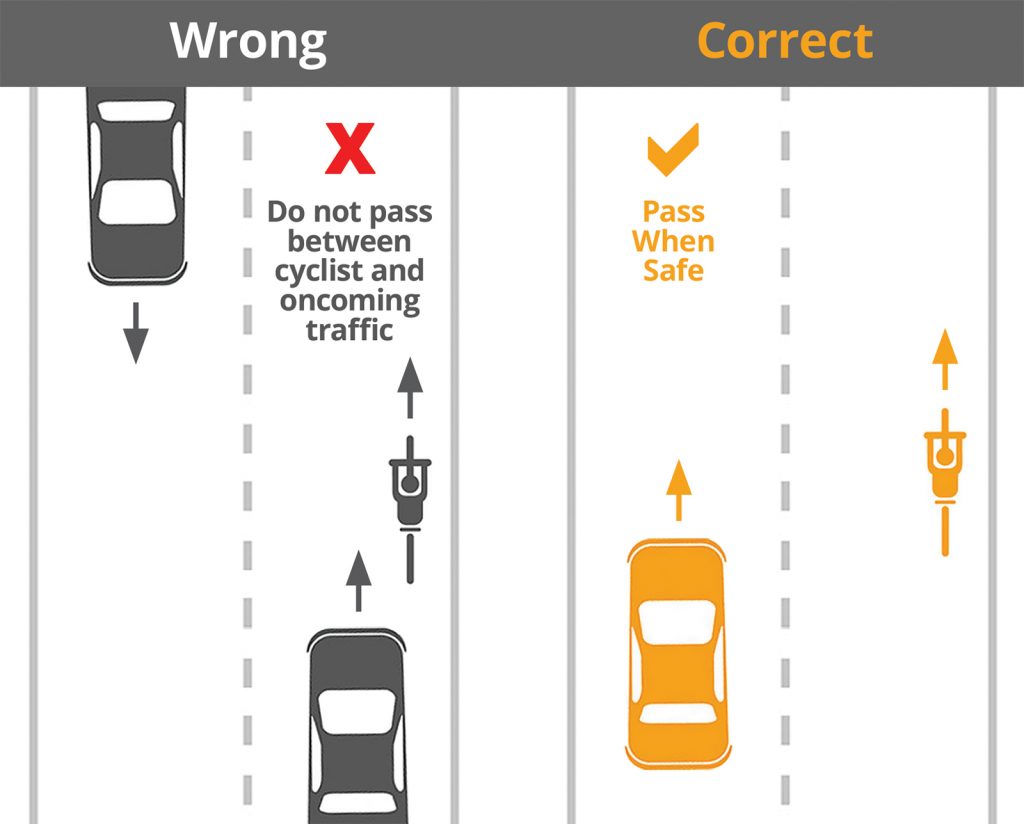

He says the greatest hazard to road cyclists are drivers who attempt to pass too closely. By law, motorists are obliged to keep a one-metre distance between their vehicle and a bicycle. Drivers who fail to do so are subject to a minimum $85 fine, which increases to $150 in designated community safety zones.

In addition, a cyclist is allowed a minimum of one metre of space on the road.

“Add the two together and you realize that a driver has to give up a minimum of two metres of the lane to pass a cyclist legally. This means that to pass a cyclist legally, a driver must make a lane-changing pass.”

Varga says one safety strategy the club has employed is to ride two-abreast on the right side of the road, a practice that has been used throughout Europe for years and one that the Attorney General’s office has confirmed is legal. When a driver approaches, the driver must wait for a safe place to make a lane-changing pass, just as they would do for a vehicle.

“I know many drivers don’t like this practice, but there is also sound law and logic behind it.” The logic being that passing a large group of cyclists riding two-up is faster than passing a group riding single file, requiring the motor vehicle to be in the oncoming lane for a shorter distance.

The Highway Traffic Act also directs cyclists to turn out to the right when a faster vehicle approaches, but Varga says the Act doesn’t fully define what that means.

However, Hachey says Section 147 of the Act makes it clear that any slower moving vehicle, including a bicycle, “shall, where practicable, be driven in the right-hand lane then available for traffic or as close as practicable to the right-hand curb or edge of the roadway” when being overtaken.

He says he witnessed a perfect example of that practice last summer when he came up to a peloton of eight riders on Old Barrie Road in his personal vehicle.

“As soon as they heard the vehicle, it was like military precision. They all of a sudden created space amongst each other and boom, single file. Then I waited to get a view and once I had the space, I passed them. And I saw in my rear-view mirror that they went back to two abreast. I wish I’d had my dashcam to post a video to twitter to show people this is how it’s done.”

In attempts to bring more clarity to rules about sharing the road, the OPP met four times with the Collingwood Cycling Club and local municipalities in the last year, and Varga says the meetings have been helpful in addressing tensions and educating riders and drivers, even if everyone is still waiting for better direction from the Ministry of the Attorney General.

The issue is not confined to Ontario. Jurisdictions around the world are grappling with how to manage the surge in bike ridership.

Denmark recently conducted a study using video camera footage at major intersections in Danish cities. The study found that 4.9 per cent of cyclists in Denmark break traffic laws while riding, while 66 per cent of motorists do so when driving. When there was no cycling infrastructure present (i.e., no bike lanes), the percentage of law-breaking cyclists rose to 14 per cent.

If this study is any indication, one way to promote better road-sharing is to improve transportation infrastructure. Municipalities throughout Grey and Simcoe counties, recognizing the many health, economic and social benefits, are investing in projects aimed at building and improving active transportation networks.

Just this spring, Grey County conducted a survey of the local population to inform a cycling and trails master plan for the county. Bryan Plumstead, Grey County’s manager of tourism, says the master plan is a high-level, long-term vision for active transportation – cycling and walking – for municipalities to use when determining infrastructure needs.

“The simple way to describe it is, what is our transportation network? What connections to we have, are there gaps in where people are trying to get to and from, and what are some of the facilities that will help them do that, on the road and on off-road trails?”

The growth of cycling events of all kinds in Southern Georgian Bay means more cyclists are coming together to form a community of competition and drawing more spectators who simply enjoy watching cycling events.

The survey was developed in an invitation-only stakeholders’ workshop that included municipalities, cycling clubs and trail advocates. It went out to the public in April and 459 people responded, the majority of whom were 51 years and older.

When asked which improvements would influence you to cycle to or use the trails more often in Grey County, the top three responses were improvements in infrastructure (27 per cent), a connected network (22 per cent) and education (14 per cent).

Plumstead says the results will be used immediately to further develop the master plan that will identify where there is a need to upgrade infrastructure, address gaps in the active transportation network and develop “amenities” such as separated bike lanes, paved shoulders and bike racks.

Currently, Grey County has 375 kilometres of off-road cycling trails as well as 143 kilometres of roads with a paved shoulder of less than one metre and 122 kilometres of roads with a paved shoulder of one metre or more.

Plumstead says safety is a key reason why the county’s transportation services department has recommended putting in paved shoulders when upgrading a roadway, and current projects include Grey Road 40 and Grey Road 13.

The cost of paving a one-kilometre stretch of shoulder is about $70,000. “It’s a pile of money,” says Plumstead, “but if you look at it over the long term of safety and maintenance, and also as a health and recreational and tourism benefit, the math works.”

He adds Grey County also promotes bike safety in other ways: through magazine articles and radio spots, distribution of thousands of Share the Road bumper magnets and through its own tourism materials.

Still, there is more education to be done: “I think there’s still a belief out there that cyclists belong on trails and don’t belong on the road, but they are vehicles under the Highway Traffic Act.”

In Simcoe County, a pilot project started in 2013 called Cycle Simcoe has blossomed into a full-fledged cycling strategy that now involves 11 municipalities.

Brendan Matheson, outdoor experience coordinator for Tourism Simcoe County, says the project started when the Barrie Cycling Club expressed a desire for safer cycling routes, and the municipality wanted to create an economic driver for an ideal cycling destination that features quiet roads, rolling hills, and waterfront routes that connect quaint towns and shops.

Matheson works with different clubs and municipalities to identify routes and trails, map them, and target gaps that require infrastructure upgrades.

Like Grey County, Simcoe has a policy that all roadway upgrades are to include shoulders that are a minimum one-metre in width.

“We partner with the planning department, the engineers, and we’re saying, ‘Hey listen, cyclists are on these roads, here’s the evidence; how can we improve cycling infrastructure here when you reconstruct this road?’”

Old rail lines have proven to be a convenient base for trail development in the region. Simcoe County just developed the 160-kilometre Simcoe County Loop Trail, connecting nine Simcoe municipalities. The county also just purchased a rail line connecting Angus to Stayner with the intent of developing another trail in the future.

“This will be a long-term project,” says Matheson. I’m hoping that one day you will be able to take the GO train to Barrie and bike from Barrie to Collingwood and beyond.”

Matheson also works with Ontario By Bike to get local businesses accredited as “bike friendly.” Currently, there are more than 80 such businesses in Simcoe County, and each one is identified on 30,000 cycling route maps that are distributed annually through the certified businesses.

In Collingwood, Collver says managing the growth of in-city cycling has spawned the development of a cycling plan to be delivered to Collingwood council this summer. Developed with the involvement of various city departments and engineers, Cycle Simcoe and cycling stakeholders, it will identify routes that are ideal for cyclists to use as well as amenities and facilities, such as places where people can safely store their bikes and avoid high-traffic areas when they go into the downtown core.

Matheson says Collingwood already has one of the most extensive crushed limestone trail networks in Ontario, with more than 60 kilometres of trails connecting subdivisions to schools, to the downtown and other amenities.

However, sharing the trails with pedestrians has also created conflict. The ideal width for multi-use trails is three metres to give cyclists and pedestrians ample room for passing, but sometimes that’s not enough. In response, the municipality has posted etiquette rules on the trails that educate users about their responsibility to share the space safely.

For safety on in-town streets, the plan will look at creating bike lanes, placing “share” emblems on the pavement to warn drivers that bicycles may be present, and identifying preferred routes for cyclists.

“It’s all a giant communications exercise,” says Collver. “More than anything, it’s trying to make sure that cyclists know where the amenities exist and motorists know where cyclists may be. That’s the effort we’re trying to make to keep everyone safe.”

As the number of drivers and cyclists in the region continues to grow, the challenge of creating a safe environment becomes that much more difficult. Better infrastructure, signage, safety campaigns and enforcement are all helpful strategies.

But everyone agrees that both drivers and cyclists need more knowledge about the rules of the road. Wansbrough believes a good start would be better instruction for young, would-be drivers when they are studying for their driver’s licence. “There should be a whole chapter on how to deal with cyclists,” she says. “There isn’t anything right now, so there’s still a lot that needs to happen.” ❧

Ride On!

Where to find biking routes, maps and other cycling resources

One only has to look at one of the maps of cycling routes in Southern Georgian Bay to realize there is no shortage of roads and trails that cyclists of all ages and abilities can enjoy. Low-traffic country roads, mountain biking trails, The Georgian Trail, the downhill course at Blue Mountain, and lots of bike-friendly businesses – the area has it all.

There are also many resources for someone who wants to cycle but doesn’t know the region. Below are some websites that can help. Some have cycling route maps that can be viewed or downloaded, while others provide broader information about the sport/recreation:

Cycle Simcoe: bikesouthgeorgianbay.ca

Ontario By Bike: Ontariobybike.ca

Ontario By Bike for Simcoe County: Ontariobybike.ca/simcoe

Ontario By Bike for Grey County: Ontariobybike.ca/grey

Collingwood Trails Map: collingwood.ca/sites/default/files/docs/culture-recreation-events/ctn_19_trailsmap.pdf

Simcoe County Loop Trail:

cyclesimcoe.ca/explore/simcoe-county-loop-trail/

South Georgian Bay Tourism website:

southgeorgianbay.ca/listing-cat/cycling/

(includes information for Clearview, Town of Blue Mountains, Collingwood, Meaford and the Bruce Trail)

Transportation Options: transportationoptions.org

(includes Ontario By Bike initiative, statistics)

Ontario Cycling Association: ontariocycling.org

(includes a listing of cycling competitions throughout Ontario)

Share the Road Cycling Coalition: sharetheroad.ca

(includes tips for safely sharing the road)

Cycling Savvy:

cyclingsavvy.org/what-cyclists-need-to-know-about-trucks/

(a video about safely interacting with trucks on roadways)